FEATURED NEW YORK STATE SUFFRAGISTS

One of eight children born to Quaker parents on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts, Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793-1880) dedicated her life to the goal of human equality. As a child Mott attended Nine Partners, a Quaker boarding school located in New York, where she learned of the horrors of slavery from her readings and from visiting lecturers such as Elias Hicks, a well-known Quaker abolitionist. She also saw that women and men were not treated equally, even among the Quakers, when she discovered that female teachers at Nine Partners earned less than males. At a young age Lucretia Coffin Mott became determined to put an end to such social injustices.

In 1833 Mott, along with Mary Ann M’Clintock and nearly 30 other female abolitionists, organized the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She later served as a delegate from that organization to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. It was there that she first met Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was attending the convention with her husband Henry, a delegate from New York. Mott and Stanton were indignant at the fact that women were excluded from participating in the convention simply because of their gender, and that indignation would result in a discussion about holding a woman’s rights convention. Stanton later recalled this conversation in the History of Woman Suffrage:

As Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wended their way arm in arm down Great Queen Street that night, reviewing the exciting scenes of the day, they agreed to hold a woman’s rights convention on their return to America, as the men to whom they had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman…was then and there inaugurated.

Eight years later, on July 19 and 20, 1848, Mott, Stanton, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt acted on this idea when they organized the First Woman’s Rights Convention.

Throughout her life Mott remained active in both the abolition and women’s rights movements. She continued to speak out against slavery, and in 1866 she became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization formed to achieve equality for African Americans and women.

Source: National Parks Service

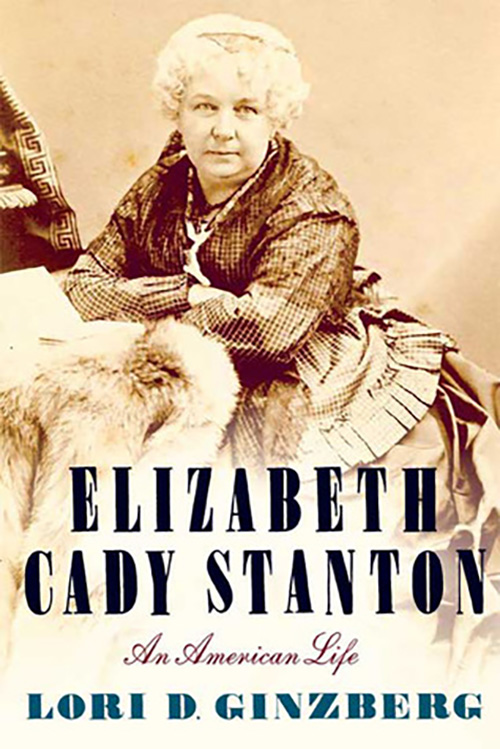

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) stirred strong emotions in audiences from the 1840s to her death in 1902. Was she catalyst, crusader or crank? Dedicated wife and mother? Privileged white woman, hiding her family's slave-holding past and stealing credit for other's work in the women's rights movement? Feminist firebrand, alienating coworkers with unnecessary controversy and uneasy alliances? Political strategist? popular speaker, philosopher and writer, who returned to the argument of individual rights in her last published speech? Lifelong friend?

For different people and at different times, Stanton was all of these. The fruits of her long life are still under scrutiny and up for debate. One thing is sure: she attracted attention and used it to push her ideas about women, rights and families for more than fifty years.

Stanton got her start in Seneca Falls, New York, where she surprised herself with her own eloquence at a gathering at the Richard P. Hunt home in nearby Waterloo. Invited to put her money where her mouth was, she organized the 1848 First Woman's Rights Convention with Marth Coffin Wright, Mary Ann M'Clintock, Lucretia Mott and Jane Hunt. She co-authored the Declaration of Sentiments issued by the convention that introduced the demand for votes for women into the debate. Her good mind and ready wit, both well-trained by her prominent and wealthy family, opened doors of reform that her father, Daniel Cady would rather she left shut. She studied at Troy Female Seminary and learned the importance of the law in regulating women through her father's law books and interactions with him and his young male law students.

At nearly six feet tall, Stanton's mother, Margaret Livingston Cady, "an imposing, dominant and vivacious figure who controlled the Cady household with a firm hand," modeled female presence. As Elizabeth entered her twenties, her reform-minded cousin Gerrit Smith introduced her to her future husband, Henry Brewster Stanton, a guest in his home. Stanton, an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society and an eloquent speaker for the immediate abolition of slavery, turned Elizabeth's life upside down. In 1840, they married against her parents' wishes departing immediately on a honeymoon to the World's Anti-Slavery convention in London. There, the convention refused to seat American female delegates. One, though short, slight, and gentle in demeanor, was every bit as imposing as Stanton's mother. Lucretia Mott, a Hicksite Quaker preacher well-known for her activism in anti-slavery, woman's rights, religious and other reforms, "opened to [Stanton] a new world of thought."

At the First Woman's Rights Convention, Mott and her wide circle of fellow Quakers and anti-slavery advocates, including M'Clintocks, Hunts, Posts, deGarmos, and Palmers, opened a new world of action to Stanton as well. Between 1848 and 1862, they worked the Declaration of Sentiments' call to "employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf." They worked on conventions in Rochester, Westchester, PA, and Syracuse and organized, sent letters to, or attended national conventions between 1850 and 1862. Stanton met Susan B. Anthony, wrote articles on divorce, property rights, and temperence and adopted the Bloomer costume. By 1852, she and Anthony were refining techniques for her to write speeches and Anthony to deliver them. In 1854, she described legal restrictions facing women in a speech to the New York State Woman's Rights Convention in Albany. Her speech was reported in papers, printed, presented to lawmakers in the New York State legislature, and circulated as a tract. Though an 1854 campaign failed, a comprehensive reform of laws regarding women passed in 1860. By 1862, most of the reforms were repealed. The Stantons moved from Seneca Falls to New York City in 1862, following a federal appointment for Henry Stanton.

In the early 1860s national attention focused on the Civil War. Many anti-slavery men served in the Union Army. The women's rights movement rested its annual conventions; but in 1863, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony created the Women's Loyal National League, gathering 400,000 signatures on a petition to bring about immediate passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to end slavery in the United States. The war over, the women's movement created its first national organization, the American Equal Rights Association, to gain universal suffrage, the federal guarantee of the vote for all citizens. Elizabeth Cady Stanton's signature headed the petition, followed by Anthony, Lucy Stone, and other leaders. But the political climate undermined their hopes. The 15th Amendment eliminated restriction of the vote due to "race, color, or previous condition of servitude" but not gender. Campaigns to include universal suffrage in Kansas and New York state constitutions failed in 1867. Anthony's newspaper, The Revolution, edited by Stanton and Parker Pillsbury, male newspaperman and woman's rights supporter, published between January 1868 and May 1870, http://www.placematters.net/node/1440 with articles on all aspects of women's lives.

Between 1869 and 1890, Stanton and Anthony's National American Woman Suffrage Association worked at the national level to pursue the right of citizens to be protected by the U.S. constitution. Despite their efforts, Congress was unresponsive. In 1878, an amendment was introduced and Stanton testified. She was outraged by the rudeness of the Senators, who read newspapers or smoked while women spoke on behalf of the right to vote. Between 1878 and 1919, a new suffrage bill was introduced in the Senate every year. Meanwhile, the American Woman Suffrage Association turned its attention to the states with little success until 1890, when the territory of Wyoming entered the United States as a suffrage state. By then, Anthony had engineered the union of the two organizations into the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Colorado, Utah and Idaho gained woman suffrage between 1894 and 1896. There is stayed until well after Stanton and Anthony's deaths.

Nothing seemed to stop Stanton. In the 1870s she traveled across the United States giving speeches. In "Our Girls" her most frequent speech, she urged girls to get an education that would develop them as persons and provide an income if needed; both her daughters completed college. In 1876 she helped organize a protest at the nation's 100th birthday celebration in Philadelphia. In the 1880s, she, Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage produced three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage. She also traveled in Europe visiting daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch in England and son Theodore Stanton in France. In 1888, leaders of the U.S. women's movement staged an International Council of Women to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention. Stanton sat front and center. In 1890, she agreed to serve as president of the combined National American Woman Suffrage Society. In 1895, she published The Woman's Bible, earning the censure of members of the NAWSA. Her autobiography, Eighty Years and More, appeared in 1898. Her final speech before Congress, The Solitude of Self, delivered in 1902, echoed themes in "Our Girls," claiming that as no other person could face death for another, none could decide for them how to educate themselves.

Along the way, Stanton advocated for Laura Fair, accused of murdering a man with whom she was having an affair. She allied the movement and her resources to Victoria Woodhull, who claimed the right to love as she pleased without regard to marriage laws. She supported Elizabeth Tilton, a supposed victim of the sexual advances of clergyman Henry Ward Beecher. She broke with Frederick Douglass over the vote in the 1860s and congratulated him on his marriage to Helen Pitts of Honeoye, NY in 1884, when others, including family, criticized their interracial marriage. Stanton was a complicated personality who lived a long life, saw many changes and created some of them. Her writings were prolific. She often contradicted herself as she and the world around her progressed and regressed for the better part of a century.

Source: National Parks Service

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born on March 24, 1826, in Cicero, New York. An only child, she was raised in a household dedicated to antislavery. Her father, Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, was a nationally known abolitionist, and the Joslyn home was a station on the Underground Railway.

In 1845 she married merchant Henry Hill Gage, with whom she would have four children. They eventually settled in Fayetteville, New York, and their home became a station on the Underground Railroad. Although occupied with both family and antislavery activities, Gage was drawn to a new cause: the woman’s suffrage movement. Her life’s work would become the struggle for the complete liberation of women.

Unable to attend the first Woman’s Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls in 1848, Gage attended and addressed the third national convention in Syracuse in 1852. She became a noted speaker and writer on woman’s suffrage.

During the Civil War, Gage was an enthusiastic organizer of hospital supplies for Union soldiers. In 1862 she predicted the failure of any course of defense and maintenance of the Union that did not emancipate the slaves.

Gage, along with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was a founding member of the National Woman Suffrage Association and served in various offices of that organization (1869-1889). She helped organize the Virginia and New York state suffrage associations, and was an officer in the New York association for twenty years. From 1878 to 1881 she published the National Citizen and Ballot Box, the official newspaper of the NWSA.

In 1871 Gage was one of the many women nationwide who unsuccessfully tried to test the law by attempting to vote. When Susan B. Anthony successfully voted in the 1872 presidential election and was arrested, Gage came to her aid and supported her during her trial. In 1880 Gage led 102 Fayetteville women to the polls in 1880 when New York State allowed women to vote in school districts where they paid their taxes.

During the 1870s Gage spoke out against the brutal and unfair treatment of Native Americans. She was adopted into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk nation and given the name Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi (Sky Carrier). Inspired by the Six Nation Iroquois Confederacy’s form of government, where “the power between the sexes was nearly equal,” this indigenous practice of woman’s rights became her vision.

Gage coedited with Stanton and Anthony the first three volumes of the six-volume The History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1887). She also authored the influential pamphlets Woman as Inventor (1870), Woman’s Rights Catechism (1871), and Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign of 1862? (1880).

Discouraged with the slow pace of suffrage efforts in the 1880s, and alarmed by the conservative religious movement that had as its goal the establishment of a Christian state, Gage formed the Women’s National Liberal Union in 1890, to fight moves to unite church and state. Her book Woman, Church and State (1893) articulates her views.

While Gage remained a supporter of women’s rights throughout her life, she spent her elder years concentrating on religious issues.

Gage died in Chicago, Illinois, on March 18, 1898. Her lifelong motto appears on her gravestone in Fayetteville: “There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven; that word is Liberty.”

Source: Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

Susan B. Anthony(1820-1906) is perhaps the most widely known suffragist of her generation and has become an icon of the woman’s suffrage movement. Anthony traveled the country to give speeches, circulate petitions, and organize local women’s rights organizations.

Anthony was born in Adams, Massachusetts. After the Anthony family moved to Rochester, New York in 1845, they became active in the antislavery movement. Antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Later two of Anthony's brothers, Daniel and Merritt, were anti-slavery activists in the Kansas territory.

In 1848 Susan B. Anthony was working as a teacher in Canajoharie, New York and became involved with the teacher’s union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of $10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her parents and sister Marry attended the 1848 Rochester Woman’s Rights Convention held August 2.

Anthony’s experience with the teacher’s union, temperance and antislavery reforms, and Quaker upbringing, laid fertile ground for a career in women’s rights reform to grow. The career would begin with an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

On a street corner in Seneca Falls in 1851, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Stanton recalled the moment: “There she stood with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray silk, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.”

Meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton was probably the beginning of her interest in women’s rights, but it is Lucy Stone’s speech at the 1852 Syracuse Convention that is credited for convincing Anthony to join the women’s rights movement.

In 1853 Anthony campaigned for women's property rights in New York State, speaking at meetings, collecting signatures for petitions, and lobbying the state legislature. Anthony circulated petitions for married women's property rights and woman suffrage. She addressed the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854 and urged more petition campaigns. In 1854 she wrote to Matilda Joslyn Gage that “I know slavery is the all-absorbing question of the day, still we must push forward this great central question, which underlies all others.”

By 1856 Anthony became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters, and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats, and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse her image was dragged through the streets.

At the 1856 National Women’s Rights Convention, Anthony served on the business committee and spoke on the necessity of the dissemination of printed matter on women’s rights. She named The Lily and The Woman’s Advocate, and said they had some documents for sale on the platform.

Stanton and Anthony founded the American Equal Rights Association and in 1868 became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. The masthead of the newspaper proudly displayed their motto, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

By 1869 Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and focused their efforts on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to challenge suffrage, Anthony and her three sisters voted in the 1872 Presidential election. She was arrested and put on trial in the Ontario Courthouse, Canandaigua, New York. The judge instructed the jury to find her guilty without any deliberations, and imposed a $100 fine. When Anthony refused to pay a $100 fine and court costs, the judge did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her chance of an appeal. An appeal would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court, but it was not to be.

From 1881 to 1885, Anthony joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage in writing the History of Woman Suffrage.

As a final tribute to Susan B. Anthony, the Nineteenth Amendment was named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It was ratified in 1920.

Source: National Parks Service

Mary Burnett Talbert, civil rights and anti-lynching activist, suffragist, preservationist, international human rights proponent, and educator, was born, raised and educated in Oberlin, Ohio. Upon receiving her college degree from Oberlin, she accepted a position as a high school teacher in Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught science, history, math, and Latin at the high school and then at Bethel University.

In 1887, she was named assistant principal of Little Rock’s Union High School, the only African American woman to hold such a position and the highest position held by a woman in Arkansas. Mary Burnett married William Talbert in 1891 and moved with him to Buffalo, NY. She was a founding member of the Phyllis Wheatley Club, the first in Buffalo to affiliate with the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. The Club established a settlement house and helped organize the first chapter of the NAACP (1910). In 1901, Talbert founded the Christian Culture Club at the Michigan Avenue Baptist Church.

Talbert also protested the exclusion of African Americans from the Planning Committee of the Pan-American Exposition. She was instrumental in the founding of the Niagara Movement, pre-cursor to the NAACP (1905). Mrs. Talbert’s club connections were extensive. In her NACW Presidential years, she transformed the association into a truly national institution with structure and organizational procedures. Its first national undertaking was the 1922 purchase and restoration of the Frederick Douglass home in Anacostia, MD. She was elected president for life of the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association.

On the international scene, she served as a Red Cross nurse during World War I in France, sold thousands of dollars of Liberty Bonds during the war, offered classes to African American soldiers and was a member of the Women’s Committee of National Defense. After the war, she was appointed to the Women’s Committee on International Relations, which selected women nominees for position in the League of Nations.

Mrs. Talbert was a pioneer in international organizing efforts, gaining a voice for African American women and developing black female leadership. With conscious intent, she bridged the generation of 19th century abolitionists and freedom seekers: Tubman, Douglass, Truth, and others, and the developing civil rights leadership of the 20th century. Addressing the Fifth Congress of the International Council of Women, Christiana, Norway, 1920, where she was the first African-American delegate, Talbert said, “the greatness of nations is shown by their strict regard for human rights, rigid enforcement of the law without bias, and just administration of the affairs of life.”

Source: National Women's Hall of Fame