Ansley Erickson, a historian at Teachers College, Columbia University, and Karen Taylor, the founder and director of “While We Are Still Here,” a Harlem-based heritage-preservation site, received an Action Grant to host two public events as part of their process in documenting Harlem’s rich tradition of education.

Ansley is Co-Director and Karen is Director of Public History at the Harlem Education History Project, which uses archival materials and oral histories to preserve and share stories of education in Harlem. Humanities New York sat with them to learn about what inspired this initiative―and Mildred Johnson Edwards, whose vision materialized a legacy of its own in the Modern School.

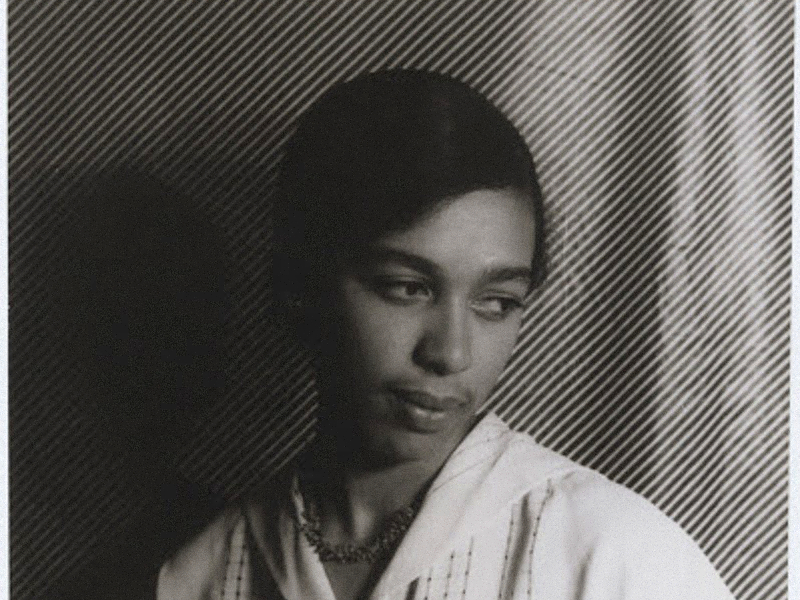

HNY: Who was Mildred Johnson Edwards, and how did she respond to the conditions in which she grew up and began her work?

Ansley: Her father was J. [John] Rosamond Johnson, who was a famous composer and musician, and her uncle was James Weldon Johnson, who was a leading intellectual and African American figure. Together her uncle and father wrote and composed the Negro National Anthem, as it was called, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

A song about citizenship, presence and participation in a nation that was denying presence and participation, and citizenship to African American people for a very long time. That’s not a direct answer to your question but I think it’s certainly part of the story…

And she’s in Harlem at a time when, because of the structures of segregation, there was relatively more class diversity than certainly was the case by the ’60s or ’70s or ’80s, when a larger number of African American families with means might have chosen to move to more suburban areas.

Karen: Mildred Johnson Edwards was an educator. She attended the New York Society for Ethical Culture [now the Ethical Culture Fieldston School].

Ansley: At the time a famous, progressive education space that was a predominantly white institution.

Karen: For her to graduate she had to student-teach. But because of racism, she was not allowed to teach white children.

Ansley: None of the predominantly white, segregated, I would say, private schools in New York would hire her. Part of the way she solved that problem: create a school where she could be a teacher.

Karen: So she found eight little children, probably about three, four, five years old. And she founded the Modern School, at St. Philips Church. She sustained that school from approximately 1934 to the late 1990s. Before it became popular in the ‘70s, Mildred Johnson Edwards was very much into progressive education; that is, more child-centered lessons and curriculum. And the level of education was high– thus far all of the people I have met who attended that school have extraordinary intellect, and they’ve achieved extremely high professional positions.

That’s the wonderful side of it.

Ansley: In the context of New York and its racial segregation, Mildred Johnson Edwards wanted to create an institution for Black children that modeled the pedegogical beliefs that she held. And yet, her need to create that school was itself a result of segregation.

HNY: How would you define segregation?

Ansley: That is a wonderfully complicated question.

Segregation, in this context, is the arrangement that we have in this country, in which most children today go to schools that are composed predominantly of children of one racial background or category. And that’s the result of a very long history of policy choices we’ve made, as well as lots of choices by individuals.

Karen: We live in a segregated society. We have always lived in a segregated society. And the United States is a segregationist, white supremacist society. Harlem was developed out of that reality. Mildred knew that she was functioning in a world that’s completely segregated and that opportunities for African American people were … constricted.

Ansley: But, defining segregation is hard, because it means so many different things in so many different ways. One way to define it is as a policy problem. Another way to define it is as a context in which people variously positioned live their lives, and do all kinds of things in those segregated spaces that gives them different kinds of meaning.

It’s also a construct that rests on these fundamentally problematic and socially contested ideas of racial categories. And so, in that way, it’s inherently problematic. We don’t really have the intellectual tools to pull apart what segregation is without recognizing that it itself rests on categories that are themselves not real. But they become real by virtue of policy and history… it’s a very tangled problem.

Karen: But that did not stop her from educating the children of Harlem.

And she had Camp Dunroven [she founded and ran Camp Dunroven from 1933 to 1965], which would extend the Modern School experience throughout the summer. They learned horseback riding and various kinds of things that are associated with, you know, middle class white America.

Ansley: The basic desire that Mildred Johnson Edwards was noticing—to create a quality educational space for children—is a basic desire that still remains present certainly in Harlem, and for many children.

In many ways, that’s a good microcosm to think about segregation, right? Which is a set of structures that are imposed upon people, outside of their control. But her story within that segregated context also really matters. In the ways that she adapts to it, and uses the networks that she has amongst African American communities in Harlem, and her own entrepreneurial spirit, to build this institution that operates as a school for roughly sixty-five years.

Karen: And in terms of the educational landscape in Harlem, there were many Black independent schools. When you had these Black communities, many times, the public school experiences were inferior, and so people called upon their agency and developed [private] schools of their own.

HNY: Why document and preserve the history of education in Harlem?

Karen: So that there’s a record. So that a record exists.

We have to retain memory. We cannot negate the importance of the history of Black people in Harlem, nor can we negate the history of the importance of Black people in the United States. Before discussing the Modern School with Ansley, I don’t think many in the Teachers College community were aware that there was this Black independent school in Harlem, that lasted for approximately six decades. It’s important to keep these histories, because history is important… It’s very, very important.

Ansley: I learned of Mildred Johnson Edwards through Karen. I learned of the institution that [Mildred Johnson Edwards] started through a student of mine, Deidre Bennett Flowers, who had actually been a student at the Modern School.

It’s not surprising that I encountered the story of the Modern School through a student. I have spent a lot of time reading books that other historians write, and some archival material about the history of education in Harlem. But, there are parts of that history that are not captured in the existing scholarship.

The story of Mildred Johnson Edwards and the Modern School is not particularly visible in the scholarship. And it’s not just her school. It’s lots of educational spaces that were created often by African American women, sometimes by African American men, in Harlem for Harlem residents and children, that have not received a lot of scholarly attention.

Or, even more pointedly: Probably have not gotten a lot of scholarly attention from people in elite positions, publishing in a sort of narrow band of a predominantly white academy.

Karen: The wonderful aspect of keeping that history—of gathering that history, of codifying that history—is that it shows Black agency. It shows self determination. And the will that Black people have, who said, “I don’t care what you say about me or my people, we are going to be educated and we are going to be highlyeducated, and there’s nothing you could do about it.”

That agency. That drive. That intense desire to be educated. I think that’s exemplified by people like Mildred Johnson Edwards.

Ansley: The Harlem Education History Project—the broad umbrella, and then our focus on the Modern School is a subset of that—that project, is inspired by the recognition that this is important history. That this is not history that’s necessarily documented well in the archives that exist.

Karen and I share the sense that oral history can be a really robust way to make sure those historical absences or disappearances don’t happen entirely, right? To some extent things do disappear, but at least we can try to create traces of time that would let us think about them in the future. Oral history tries to prioritize the voices of the people who have these experiences themselves, and have their stories shape the documentation that’s created.

HNY: Can you walk us through the organization of the public recording events?

Ansley: Karen conceptualized a “multigenerational reunion.” Then, we made oral history a part of that day. We started with a panel in which several alumni and one scholar spoke in front of about one hundred alumni. While those were not formal oral histories, they were story-sharing times that set the tone for the day. [This day] became another venue where people were telling their stories, sharing about experiences at the school.

Later in the afternoon, we sat with people who volunteered to be interviewed. They talked about what their experience was at the school, how they had come to be at the school, what their recollections were from their time there, how they reflected on the school later in their life. Several people who participated had become educators, so they often were thinking about the relationship between what had happened at the school and their later choices.

And with the support of Humanities New York, we did two additional events in which we invited alumni to join us for more interviews. One woman who was both a student and then a board member at the school, joined us for two sessions. We knew more about the school having heard from the first set of people, so we were a little bit more informed about what kinds of things to be listening for and asking people to reflect on [And we had met with a group of alumni before hand, to discuss the project and confer about themes for the interviews].

HNY: Who conducts these oral history interviews, and what do you hope they gain from this multigenerational, cross-cultural exchange?

Ansley: The oral history interviews are conducted largely by students here at Teachers College, who have taken a class with me in oral history practice, and also a class focused on preparing for this particular oral history project. If I can teach a class and I can have six or seven students interested in doing interviews, then we can do a good body of interviews.

It’s also a really valuable pedagogical space because students here, who are either future historians or future educators, get the chance to sit down and listen to people who can reflect on how important schooling was to them; can describe educational experiences that were really consequential for them.

I think oral history, and especially listening to somebody’s account of their childhood in school, is a really fundamentally humane experience. I would hope that it creates, for future teachers, or anybody working in education, a sense of both aspiration—you’d like to be a part of helping someone feel as connected to and as supported by their schooling, as we were hearing from people about the Modern School.

But also some sense of humility—when you work with children you’re doing work that shapes people’s lives.

HNY: What’s next for the Harlem Education History Project?

Ansley: Since the first event in 2017, and every time we’ve done an oral history recording day, we’ve also created an informal museum, where people who came to be interviewed can listen to and see the other materials that we have gathered.

Actually, [an] important audience for these oral histories is the Modern School community itself. People really enjoy getting to hear their friends and former friends, or people from a different generation, with their own recollections.

I think Karen would say—maybe you’ll ask her—that this should be a documentary video project. And maybe it should be.

Karen: I would love to do a documentary.

Ansley: But I hope that this particular kind of story, about an autonomous educational space created and led by a Black woman for sixty years, becomes part of what scholars and public historians think of when they think about what education in Harlem looked like.

HNY: Why ought funders support oral history preservation projects?

Ansley: That’s a very big question. It’s a very important question.

To the point about listening to people’s stories: We are all individuals trying to make our way in the world. I fundamentally think we can do better when we have a sense of what people’s stories have been before us. And those stories can inspire us, those stories can challenge us, those stories can humble us. I think that’s a really valuable part of learning.

And if we don’t fund history, it doesn’t necessarily get preserved. It doesn’t necessarily get taught, and it doesn’t necessarily become available to people who could benefit from encountering it.

Karen: I cannot underestimate the importance of community. I think having a community—that has the same historical imperatives, the same kind of historical experiences—is important, for every person. For people to have a sense of their own powerful histories, and their contributions to the world. That’s really important.

And I’m talking about all people—not just Black people, not just white people, not just straight people, not just gay people.

Ansley: I think Humanities New York’s interest in not just having historical resources exist but putting them into conversation with audiences and communities that can care about them, is also really important. That emphasis on public programing I think is really important.

Karen: It’s an even more wonderful thing when those various communities can come together towards the liberation of humanity. People have to call upon their self-determination and their agency to make the world a better place.

HNY: And one last question before we go. How does legacy define this project?

Ansley: When alumni remember the presence of their principal, who is also sometimes their teacher, and they remember viscerally how they felt as children… clearly Mildred Johnson Edwards is present in their lives.

There are a lot of people who went there who really appreciate the experience they had, and that matters a tremendous amount. In a couple instances in interviews, people have commented on the kinds of decisions they’re making for their own children. It seems quite clear that their decisions are shaped in some way by the experience they had as children.

That’s a legacy. That’s Mildred Johnson Edwards, having created something that is shaping the education of people a hundred years beyond her passing.

And my hope is that other people down the road will be able to connect to her story, and so that the legacy—that her legacy, is not just about the particular students [she had] worked with. It’s about the ways in which her story can cause people in education, people working in African American communities, African American community members themselves, to reflect on what this history is and what it means for the future.

You can learn more about the Harlem Education History Project on the web and on Twitter, @EduHarlem.

Keep up with HNY, join our newsletter.

Interviewed by Kordell K. Hammond, HNY Graduate Intern

Ansley T. Erickson, Associate Professor of History and Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. Co-Director, Center on History and Education. Affiliated Faculty, Institute for Urban and Minority Education. Affiliated Faculty, Columbia University History Department

Ansley T. Erickson is a U.S. historian who focuses on educational inequality, segregation, and the interactions between schooling, urban and metropolitan space, racism, and capitalism. Her first book, Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2016 and won the History of Education Society’s Outstanding Book Award in 2017. Her work has also been awarded the History of Education Society Prize (2016), the Bancroft Dissertation Prize (2010), and the Claude A. Eggertsen Dissertation Prize (2011).

Erickson co-directs the Harlem Education History Project (HEHP) with Ernest Morrell, Coyle Professor of Literacy Education at the University of Notre Dame. HEHP supports a digital history project and collaborations with local schools. The project has produced an edited volume, Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community, that was published by Columbia University Press in November 2019 and available online as a free enhanced digital edition at harlemeducationhistory.library.columbia.edu.

Karen D. Taylor is the founder and executive director of While We Are Still Here, a heritage-preservation organization founded to ensure that the “‘post-gentrification’ community of Harlem and beyond will honor and find a meaningful connection to the legacy of African-American achievement, and its paramount importance to world culture.” Ms. Taylor produced and directed a feature-length documentary film, In the Face of What We Remember: Oral histories of 409 and 555 Edgecombe Avenue, which was a Reel Sisters Film Festival selection, as well as a selection of the Inwood Film Festival.

Additionally, she consults as the director of public history for Teachers College-Columbia University’s Harlem Education History Project. Ms. Taylor is currently completing a memoir, Calypso Blues: A Black Woman’s Song In White America, which recounts her experiences as a woman of African-American and Barbadian heritage.

She is also a multi-genre artist, who has appeared as a vocalist and poet at the Schomburg’s Women In Jazz series; and at Transart’s Jazz In the Valley, she premiered a spoken-word/music tribute to Jayne Cortez, “A Jazz Fan Looks Back.” Her essay, “Still Occupied: My Report on the Safety of My Sons,” published in Transition Magazine was cited in the Notable Essays and Literary Nonfiction Category, in 2016 Best American Essays, edited by Jonathan Franzen. She has also had articles published at espnW.com, the Amsterdam News, Downbeat, and Essence.

Ms. Taylor received an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts in Creative Nonfiction.