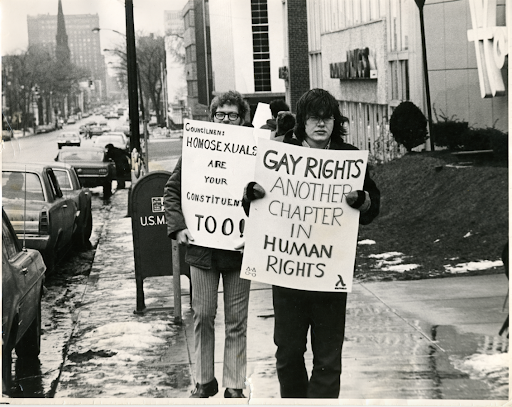

Fifty years since the historical uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. Fifty years since the founding of Buffalo’s earliest gay rights organization, the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier. Which is the more significant for Buffalo? Humanities New York funded “Gay Liberation NOW: Buffalo Mattachine and the Myth of Stonewall” to shed light on the story of how the struggle for gay liberation in Western New York evolved, in parallel to Stonewall but not because of it.

Humanities New York spoke with grantee Adrienne Hill, who co-founded the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project. Hill lays out how teaching LGBTQ history to an audience of college students in 2012 rural Ohio inspired her to rethink the dominant narrative of LGBTQ histories, both in Western New York and nationally.

HNY: Can you talk about what informs your style of activism, and if it shifted when you made the move to Buffalo?

Adrienne: Before I lived in Buffalo, I was in grad school at Bowling Green State University, which is in Northwestern Ohio. It’s a college town about a half hour south of Toledo; very rural area, even more so than Buffalo, arguably.

I was teaching gender studies classes, and Intro to LGBTQ Studies. I realized a lot of my students knew something about LGBTQ history, but what they knew–or what they thought they knew, was that it was something that happened only in New York City and San Francisco. I think that’s the dominant narrative of LGBTQ History in America; that it happened basically in those two cities and that everywhere else may have built a movement but they did it later and not as competently.

Especially like a rural area like where I was living in Ohio, the dominant narrative that we have about LGBTQ people across this country in those rural areas is that that’s where LGBTQ people die… It’s not where they live; it’s not where they survive; it’s not where they build communities or movements. And I saw that that was really tough for a lot of my students. So I started to get interested in what it would mean to take LGBTQ history and movement-building seriously, as it originates out of smaller communities. I don’t know if I really found that answer in Ohio.

Buffalo is a really great, fortunate place to study LGBTQ history and movement-building, because some of that has already been built. A couple of things that it’s famous for is a book called Books of Leather, Slippers of Gold written by local activists, which studies the working-class lesbian bar scene here in Buffalo in the 40’s and 50’s. Of course, the famous novel Stone Butch Blues is partially set in Buffalo and based on actual Buffalo places. Madeline Davis, who co-wrote Books of Leather, Slippers of Gold, helped put together the Madeline Davis Archives, which is one of the largest LGBTQ archives in the US. And if you want to learn how a mid-sized city movement builds, that’s where you go.

It was sort of this fortunate coming together of a certain desire I had to learn about smaller communities and LGBTQ movement-building, plus a certain set of resources that we happen to have here in Buffalo, that lead me towards the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project.

HNY: Can you share with us some accomplishments and proudest moments the program has encountered since its founding in 2016?

Adrienne: The organization was co-founded by me and by my friend Bridge Rauch, who kind of suggested it to me. And so, it started out as a dream between two people sitting in a coffee shop. And now, our meetings attract about 20 people and we have a volunteership regularly of about 15 people. Our events used to be really small; they now attract about one hundred people on the regular.

This year, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Stonewall – which was also the 50th anniversary of the founding of Buffalo’s first gay rights organization – we did a panel of founding members of the Mattachine Society. Much of what we’ve been doing is taking what’s already available in the archives and making it accessible to people, and some of that has been interrogating what isn’t yet in the archive and why it’s not there, and what can we do to expand our historical archives. The Madeline Davis archives are huge, but, they are overwhelmingly white.

We partnered with a couple of Black LGBTQ groups here in Buffalo: Black Intelligent Ladies Alliance (BILA), and another called Black Men Talking. And we partnered with the only lesbian bar in town, which is also the only Black queer bar in town, and we put together an event called “Black In Time.” This was last year in April, and we had been talking to a couple of local Black, gay activists and uncovering a story that has never been covered in the gay media, which is predominantly white.

In ‘77, there was a famous bar here called Mean Alice’s, and they were really known for being ‘expressly gay’ for calling themselves a cruise bar. They were super popular, but they were also notoriously racist; the official policy there was that you had to have four pieces of identification to get in. And considering this was the ‘70s, driver’s licenses were not necessarily photo ID. They wanted four pieces of photo ID. And, of course, they would selectively enforce that rule depending on who they wanted to be in the bar.

“And when he tried to file a second complaint the division of human rights said,‘well why do you want to be there anyway?’”

Two Black, gay men – John Morrison and Robert Harrison – tried to get into Mean Alice’s and they were not let in because, quote-unquote, “They didn’t have enough ID.” They later filed a complaint with the division of human rights. Morrison didn’t win his case because even though he was of age, he quote-unquote “Looked young.” Mr. Harrison won his case–he was awarded $500 but shortly after he got that award he tried to get into the bar again, and was kept out again. And when he tried to file a second complaint the division of human rights said, ‘well why do you want to be there anyway?’

In some ways it’s remembered as a victory even though it wasn’t materially a victory because it was one of the first times queer people of color fought back in Buffalo. This didn’t result in opening up the bar but it resulted in the strengthening of the Black gay community and the creation of a lot of different parties around the area, like Just Us, that were really about creating space for Black gay people.

HNY: When we think about Stonewall 50 we tend to ignore what was happening outside of New York City, sometimes even what was happening in other parts of New York City. If you can, tell us more about Madeline Davis, and what was happening in Buffalo before or at the same time as Stonewall?

Adrienne: One of the things we have been talking about in our program is that Stonewall is an important, legendary touchstone, and I don’t want to diminish the accomplishments of people who were present at Stonewall by saying that. But, its functions aren’t necessarily the actual beginning of the gay rights movement. People in Buffalo did hear about Stonewall and they were inspired by it, but also it’s not as if resistance was not happening in Buffalo parallel to what was happening in Stonewall.

Bobbi Prebis, who is a working-class butch lesbian and who was part of the founding of Madeline Davis archives here, had tried to organize other gay people in Buffalo in the mid and late 60’s, prior to 1969. But she just couldn’t make it happen because gathering places didn’t last long enough to make that viable, essentially. And so what happened was there was a man named Jim Garrow, and he owned a bar that was, problematically, named The Tiki. He was denied a renewal of his liquor license and was forced to close down The Tiki, because he was known to be gay. And that was … well, a lot of the older people here in Buffalo remember that as their Stonewall moment; not because there was a literal riot but because that was the tipping point of just ‘they won’t let us meet.’

And so Jim Garrow, late in 1969, created a place called The Avenue which was a gay coffee and juice bar. Not because he was concerned about sobriety but because he couldn’t get a liquor license. A group of activists met in The Avenue, and they had invited Frank Kameny, of the Mattachine Society of Washington D.C. to come over and advise them on how to fight back. And he basically said, ‘Look, just write a constitution, put the constitution in a drawer and start organizing for your rights.’ And so that night the Mattachine Society of the Niagara Frontier was born.

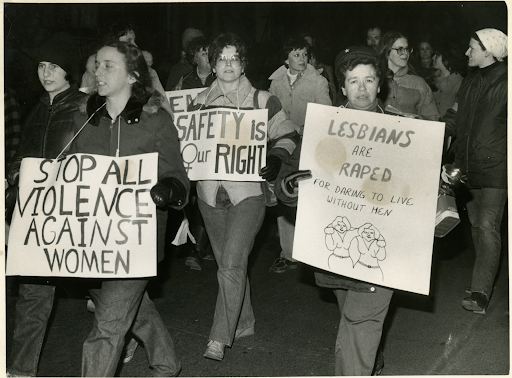

That happened I think in the early 1970’s, and they kept meeting at The Avenue, which was down the street from the Erie County Holding Center. And the police were NONE to pleased that a bunch of gays were organizing for their rights right under their noses. We did actually have a raid in April 1970. The Avenue was raided: eleven people were arrested; ninety-four people were evicted; and two lesbians tried to hold down the bar and tried to defend it against the police and they got brutally beaten. That was really another galvanizing moment; people were interested in building a movement but then they realized that they were gonna have to fight for it.

The gay rights movement in Buffalo was being founded just as Buffalo’s economic decline was starting, and so that makes it also harder. People tend to batten down the hatches and be a little more conservative when they’re scared for their material futures. And so that made it a little bit harder for them to fight for their rights.

You can do a lot of things by mobilizing relationships. Where that becomes problematic is, if you’re LGBTQ, the first hurdle in mobilizing those relationships is coming out of the closet. That could be really dangerous, especially in a period of economic decline. If you look at like the 1950’s and you look at lesbian culture in Buffalo, there are a lot of out proud butches who [did not care what you thought]. And they were able to not [care what you thought] because there was a lot of work available for them, so if one plant didn’t want to hire them because of the way they dressed they’d just get a job elsewhere. Just as the organized gay rights movement is beginning that kind of approach of “I don’t care if you fire me because I’ll just go get a job someplace else” is going away. People are becoming a lot more protective of their sexuality. Being able to risk yourself is a big hurdle to overcome.

I think what we’re trying to figure out is what an intersectional movement looks like now as our city is gentrifying but job availability is not keeping pace with housing prices.

HNY: With events like the Stonewall uprising, and with respect to these historic figures and their legacies, how do we best honor the past and respectfully celebrate the fruits of past victories?

Adrienne: For me, history is a living thing. For me, the way that you honor those seeds that were planted is to just keep tending them. And to pay attention to what they grew, whether it was good or bad–often a little bit of both. We have started to build a relationship with some teachers, and definitely curriculum development is where we want to move next and there has been some definite interest in.

I think that ever since Humanities New York got involved it’s really helped us with our marketing game, so that’s helped us really get the word out about what we’re doing and why it’s important, and that’s definitely helped us grow our audience. I can’t say enough about you – You’re great!

Interview by Kordell K. Hammond, HNY Graduate Intern.

To learn more about the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project, you can find them on Facebook and Instagram.

Read part one and part two of the Stonewall 50 series.

Poster, top, designed by Amanda Killian. Features ‘70s-era line art from Buffalo’s gay newspaper, Fifth Freedom. The original line art was by Greg Bodekor.

Adrienne Hill is a Buffalo, NY-based activist and writer, and the co-founder of the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project.