A divided movement brought about the Nineteenth Amendment.

By Lisa Tetrault

In 1869, a bold new idea was born. It would have been inconceivable a few years earlier. Upending everything about the balance between state and federal power, this idea strove to remake American democracy. It proved so vexing that we are still sorting out its implications.

“Woman’s Suffrage by the proposed Sixteenth Amendment is before the nation for consideration,” one newspaper heralded. Demanding their enfranchisement through a constitutional amendment, “women,” another column remarked, “strike out in a new path.” Women had been demanding the vote for some time, but this new approach was extremely far-fetched.

Although we assume today that voting is a basic right of citizenship, enshrined somewhere in the Constitution, the original Constitution actually sidestepped the issue entirely. It did not define or safeguard any individual’s right to vote. Rather, at the nation’s founding, individual states held jurisdiction over making (and regulating) voters within their boundaries. Women were now saying that this should be reversed—that the federal government, not the states, should make women into voters.

Roughly fifty years after a handful of suffragists conceived the idea, it became a hard-fought reality. In 1920, states ratified the Nineteenth Amendment and thereby guaranteed voting rights to women across the country. Or so it is said.

As the so-called women’s suffrage amendment approaches its one hundredth birthday, it remains poorly understood—even among those who celebrate it. Just what did the Nineteenth Amendment do? Why is this long-lived campaign alternately revered and maligned? And why do the constitutional issues it helped to open remain so unsettled? Answers to all these questions require a look back at this spectacular campaign, replete with triumphs, reversals, infighting, heartbreak, and joy.

The Origins of a Federal Amendment

Although women demanded the vote as far back as the 1840s, they did not call for a federal amendment until after the Civil War, when a new battle over the status of recently emancipated freed people split the nation. What rights should former slaves have, if any? Rejecting most of African Americans’ demands upon freedom, a band of congressmen nevertheless supported freedmen’s demands to vote. They proposed to accomplish this through amending the Constitution.

Passing Congress in 1869, the Fifteenth Amendment declared that voting “shall not be denied or abridged . . . on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” When ratified in 1870, the amendment struck down state requirements that voters be “white,” enfranchising black men nationwide. This creation of voters through federal amendment had never before been tried.

Congressional passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, however, tore apart the feminist-abolitionist community and split the movement. Often working together in the same prewar coalitions, women’s rights and antislavery advocates regrouped after the Civil War to form the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). The AERA advocated the enfranchisement of both African Americans and women, as twin demands.

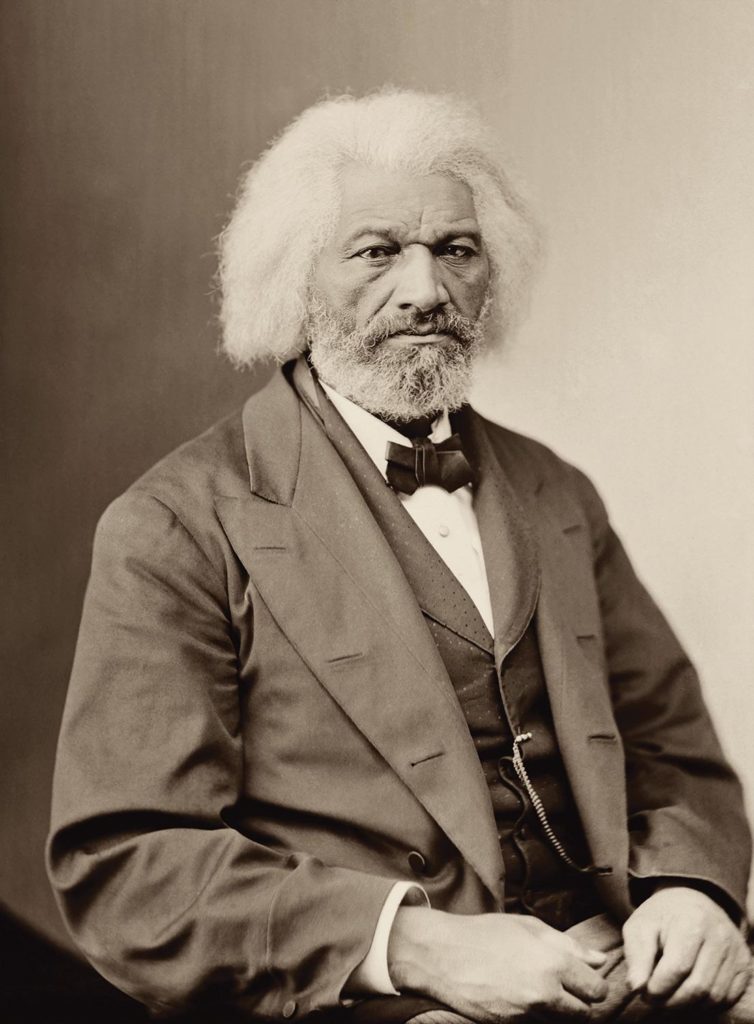

When the Fifteenth Amendment advanced only one of those goals, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony—leading suffragists—balked. At the group’s 1869 annual convention, the pair refused to support the amendment’s ratification because it omitted women. Frederick Douglass—who had escaped slavery and, by this point, become the nation’s leading African-American statesman—defended the amendment as an important step forward. Sparks flew as the trio sparred.

Stanton trotted out racist defenses for her opposition. She railed against “ignorant” black manhood voting before “educated” white womanhood. And she hurled racial epithets, calling black men “Sambo.” Not only would (to her mind) unfit freedmen be allowed to vote, she warned, but immigrant men too, increasing the ranks of “ignorant,” incompetent voters to epidemic proportions.

Anthony backed up Stanton. If the vote was to be given “piece by piece,” Anthony shouted, “then give it first to women, to the most intelligent & capable of the women at least”—clearly meaning native-born white women and displaying her own deeply held sense of racial hierarchy.

Douglass countered. Ongoing vigilante violence across the South gave black men greater priority, he argued. “I do not see how any one can pretend that there is the same urgency in giving the ballot to the woman as to the negro,” he began. “With us, the matter is a question of life or death. . . . When women, because they are women, are hunted down . . . when they are dragged from their houses and hung upon lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed out upon the pavement, . . . then she will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.”

A Divided Movement Is Born

Angrily, Stanton and Anthony bolted from the AERA and formed a new organization, the National Woman Suffrage Association. Stanton and Anthony used their National Association to oppose the Fifteenth Amendment and advocate for their newly conceived idea for a Sixteenth Amendment, granting women’s suffrage.

In their eyes, the Fifteenth Amendment had only one redeeming feature: It had nationalized suffrage, shifting voting regulation from the states to the federal government. This meant suffragists no longer had to labor at the state level, attempting to remove the word “male” from the voting qualifications in each and every state—an excruciatingly onerous fight. Now they could focus all their energies on a single citadel, the U.S. Constitution.

Not all suffragists agreed with Stanton and Anthony’s constitutional logic, however. Their rivals in the AERA, which included most of its leading membership, countered the pair by forming an opposing American Woman Suffrage Association. Overseen by Lucy Stone—a prominent white reformer and peer of Stanton and Anthony—the American Association not only supported the Fifteenth Amendment, but also insisted the vote must still be won in the individual states. They rejected Stanton and Anthony’s arguments that constitutional authority around voting in the U.S. had been remade. The Fifteenth Amendment had been no more than a postwar exigency, ratified in order to redress the evil legacies of slavery.

Black women, who long had a tradition of independent organizing, moved in and out of both organizations, but mostly they pursued their own vision of rights work, often in collaboration with black men. While they sometimes sought alliances with white women and supported suffrage, black women often found the two mainstream suffrage organizations too narrow, incapable of expressing their broader and racially informed visions for justice.

Two Approaches to Amending Constitutions

Although ratification settled the battle over the Fifteenth Amendment, the question of which constitutions to revise in order to win women’s suffrage remained open.

The American Association worked to get the word “male” removed from the list of voter qualifications in states’ governing charters. To remove it, many states required that the proposal pass two successive state legislative sessions. Some legislatures met only every other year, however. And where the proposal passed one session of a state legislature, it might not pass the second, meaning the process would have to begin all over again. In other cases, efforts to win women the vote had to pass a state referendum, going before the all-male voters of the state.

Although cumbersome, these strategies showed signs of promise when, in 1869, the same year the AERA split, Wyoming enfranchised women. A year later, in 1870, Utah did the same. Elsewhere, state constitutional conventions and state legislatures routinely took up the issue.

The National Association, by contrast, experimented with how the federal government might be leveraged to secure a citizen’s right to vote. Because amending the Constitution was enormous work, in the early 1870s, they began trying out interpretations that the Constitution already enfranchised women. Voting was a basic right of federal citizenship, they argued, and, as citizens, women were entitled to vote. In 1875, however, the Supreme Court pushed back, deciding in Minor v. Happersett that voting was a privilege, not a right.

This ruling was devastating for the pursuit of voting on the explicit grounds of “rights.” The National Association’s petitions for an amendment were now patterned on the Fifteenth Amendment, emphasizing nondiscrimination. Just as that amendment banned states from discriminating in voting on the basis of “race,” their congressional petitions requested an amendment that would effectively strike down as unconstitutional all state qualifications that voters be “male.”

Amending the U.S. Constitution, however, would not be easy or simple. A federal amendment first had to have a congressional sponsor, a congressman (as all were men) to introduce it into the legislative session. Next, it had to pass both chambers of Congress (in the same session) by a two-thirds majority. Ratification, in turn, was its own herculean task, requiring approval by three-fourths of the states. And there could be no incremental victories. It was all or nothing.

The amendment appeared to gain traction in 1878, when Senator Aaron Sargent—a Republican from California, whose wife, Ellen, was an ardent suffragist—introduced the amendment into Congress for the first time:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

“Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

For almost a decade, however, the amendment remained stalled in committee until, in 1887, the Senate rejected it by a hefty margin.

Winning women the vote could not be accomplished by a single vote. Suffragists had to wade through layers and layers of power and process. There were endless politicians to coddle and cajole, not to mention the always-scarce resources needed for their voluminous campaigns. This was exhausting work, and keeping momentum alive, over decades, was itself a full-time job.

The Difference the States Made

After almost twenty years of little progress, the state strategy once again bore fruit. Colorado enfranchised women in 1893. Idaho followed suit in 1896. By the close of the nineteenth century, women were voting on equal terms with men in four states.

Although the state and federal campaigns were separate strategies, they were often two sides of the same coin. The federal amendment would likely never have passed if the individual states had not begun enfranchising women in rapid succession around the turn of the century.

Added to the original six states or territories came another eight, all west of the Mississippi: Washington in 1910; California in 1911; Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon in 1912; the Territory of Alaska in 1913; along with Montana and Nevada in 1914. By 1915, western women were voting in massive numbers. Then key eastern states began to fall. In 1917, New York suffragists scored a huge victory when the Empire State agreed to remove “male” from its voting requirements. A year later, Michigan did the same. Then came Oklahoma and South Dakota.

A host of other states began extending partial suffrage rights to women. Women could vote in certain types of elections, but not in all elections—meaning not on equal terms with men. Nevertheless, women began to vote in states that had not even amended their state constitutions. Women gained what was called “school suffrage” (voting on school matters), “municipal suffrage” (voting in municipal or city matters), and “presidential suffrage” (voting for U.S. president). By 1920, there were only eight states in which women were not already voting in some fashion.

Unfortunately, most of the aged, original, nineteenth-century suffragists died before these cascading state victories. Stone died in 1893, Stanton in 1902, and Anthony in 1906. Few who had inaugurated the fight would live to see these victories.

Yet as the word “male” was struck from state voter clauses, many states began to formally strip away poor-white and non-white men’s ballots. In 1890, white supremacists in Mississippi passed the first of the Jim Crow restrictions—poll taxes, literacy tests, and more—whereupon other states followed. By 1913, many states across the nation (not just in the South) had placed significant new restrictions upon voting. Although these tests were often selectively administered against men of color—Latino, black, and immigrant—their precise language nowhere mentioned race, giving such restrictions plausible deniability of being, in fact, race-based, and thus making them legal under the Fifteenth Amendment.

For black women suffragists who had also inaugurated this fight—such as Sojourner Truth (died 1883) and Sarah Parker Remond (died 1894)—such laws represented not only dreams deferred, but dreams destroyed. These new laws did what vigilante violence had not been able to fully accomplish: Throwing most men of color off the voter rolls, until their voting numbers dwindled to almost nil.

A Federal Amendment Won

Some say Alice Paul brought the fight back to Congress. In 1890, just as Mississippi threw men off the voter rolls, the National and the American Associations unified, forming the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Anthony handpicked Carrie Chapman Catt to lead the organization. Catt was a longtime activist who had risen through the suffrage ranks under Anthony’s tutelage. Catt, however, believed that a direct fight for a federal amendment was unwinnable, and that the battle had to proceed state by state. When enough states fell, she predicted, so too would a federal amendment.

Alice Paul, meanwhile, was impatient. A much younger suffragist who had cut her teeth in militant suffrage activism in Great Britain, Paul believed that a direct fight for the federal amendment should be revived. Paul clashed with Catt and soon left NAWSA to form her own suffrage organization, the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

The NWP not only demanded a federal amendment—immediately—but they did so in ways that made Catt cringe. Their brash, militant tactics were an about-face from Catt’s careful diplomacy. Paul and her NWP comrades were responsible for much of the gripping drama that we associate with the final push for the Nineteenth Amendment.

In 1913, they held a massive suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.—the largest peaceful protest ever assembled on D.C. streets to that point. To skewer President-elect Woodrow Wilson for his opposition to women’s suffrage, they held their parade on the eve of his inauguration, upstaging him. Crowds physically attacked the marchers, and scores of women were sent to the hospital.

Then, beginning in 1917, Paul and her allies began peacefully picketing the White House. When decorum dictated they lay down their signs as the United States entered World War I, they went right on picketing. Wilson had had enough. He had the women arrested on trumped-up charges of “obstructing traffic.” But as one group of women went to jail, another row of picketers took up their posts. Soon over a hundred women were put in jail, where some began hunger strikes. The prison ordered the women force-fed, as the correction officers gruesomely poured liquid nutrients down tubes forced into their throats.

These “silent sentinels” ceased their protests only when, in 1918, Congress agreed to bring the federal amendment to a vote. When that vote failed, they posted themselves back outside the White House. Wilson, meanwhile, finally declared his support.

By 1919, the tides had turned. On May 21, the House passed the amendment by a relatively large 42-vote margin. And, on June 4, the Senate followed suit, 56 for and 25 against. The amendment had carried and was headed to the states for ratification.

Although the story often focuses on Paul and the NWP for reasons of sheer drama, Catt’s plodding ground game had been just as important. The scores of women already voting across the nation had convinced many that women’s suffrage would not throw the world off its axis. Those voting women had also helped send pro-women’s suffrage politicians to Congress. The networks Catt and NAWSA had built in the states, moreover, proved critical to this next fight.

The 14-month ratification effort had a promising start. Then panic set in. The quick succession of ratifying states slowed, then stopped—one short of the 36 states needed. Five excruciating months went by, as no states considered it. That fall, the governor of Tennessee shocked everyone by calling a session of the Tennessee legislature to affirm his state’s opposition.

Because Tennessee was a southern state, known for its fierce opposition to women voting, prospects looked grim. Battalions of suffragists and armies of their opponents descended on Nashville, the state capital. Lobbying went on through the night preceding the vote. As roll call began the next day—August 18, 1920—it seemed clear the amendment would not pass.

But upon receiving a letter from his mother, urging his support—and instructing him “to be a good boy”—Harry T. Burn, the Tennessee legislature’s youngest member, at only twenty-four, changed his vote. Burn declared his support. His courage caused one more defection from the opposition. And, shocking everyone, the Tennessee legislature approved ratification by a two-vote margin. The long and arduous fight for a federal amendment—which had taken decades, involved millions of women, and exacted an enormous toll—was finally over.

Newspapers trumpeted victory. “SUFFRAGE WINS,” read the front page of one, “Tennessee House Ratifies . . . Giving Women of Entire Nation Vote.” “The federal suffrage amendment has granted women the right to vote,” read another.

The Still Elusive “Right to Vote”

Victory, however, was not as conclusive as celebrations made it seem. There exists—then and now—considerable slippage between what the amendment did and what Americans claim for it. The amendment, like the U.S. Constitution, neither creates nor extends any “right to vote.” The amend-ment had also not secured voting for “women of the entire nation.”

In fact, discrimination in voting was still perfectly legal, as long as it was not explicitly based on “race,” and now “sex.” Otherwise, states were free to discriminate in whatever ways they chose. And discriminate they did—all across the country.

Turn-of-the-century laws that had disenfranchised black men in the South now also prevented black women from voting. Although the qualification of “sex” no longer barred them, selectively applied literacy tests, poll taxes, and more still did.

Nevertheless, black women showed up en masse across the South to test these limits, displaying enormous resistance to the edifice of white supremacy. In some cases, black women defied the odds and managed to vote. But, like black men, they were largely prevented from doing so. When Indiana Little, a Birmingham schoolteacher, went to register in 1926, white officials arrested her on charges of vagrancy. And when Susie Fountain, of Pheobus, Virginia, attempted to take that state’s literacy test, the white registrar handed her a blank sheet of paper. Naturally, she failed.

Discriminatory laws kept women of color from voting in the North and West as well. During the early 1900s, native-born whites in both regions worked to “purify” the electorate of “problem voters,” which largely meant immigrants and voters of color. Numerous northern and western states expanded their residency requirements for voting, tightened registration requirements, and shortened registration windows. Twelve northern and western states—from New York to California—also added literacy tests to their state requirements for voting. Like those in the South, these tests were often selectively administered against voters of color, including women. Yet because neither “race” nor “sex” was mentioned in the letter of these laws, they were also perfectly constitutional. Still others, particularly Asian, Pacific Islander, and indigenous women, were barred from voting by restrictions on their citizenship.

This countervailing reality of women’s ongoing disenfranchisement underscores just what had been lost when the amendment text had shifted to enshrine only nondiscrimination instead of a constitutionally given right to vote. As white suffragists watched the Fifteenth Amendment crumble after the 1890s, why hadn’t they ditched this single-grounds, nondiscrimination approach and revised the text to demand a citizen’s right to the ballot? The narrow wording of the Nineteenth Amendment, unchanged since 1878, was likely a concession to multiple factors, including that women understood after the Minor decision that decisively claiming a “right to vote” was unlikely to pass, given how radically it would remake the Constitution. At the same time, this was also a concession to American racism.

Many white suffragists believed that discrimination in voting on other grounds was desirable. Stanton, for example, had always supported an educational test for voters, something on full display in her 1869 objections to the Fifteenth Amendment. The same was true for other suffragists, and this text allowed for discrimination on myriad grounds, as long as the reason was not “sex.”

When millions of women protested their continued disenfranchisement after 1920, the mainstream, largely white suffrage organizations refused to listen. White women declared victory. And, in the process, they—just as their amendment had—tacitly condoned the continued operations of American racism.

Meanwhile, scores of women continued their fight for this elusive right, something they would not secure until the 1965 passage of the federal Voting Rights Act, which, together with subsequent reauthorizations, tore down many of their obstacles to the ballot.

For all its merits, the Nineteenth Amendment, like the Fifteenth Amendment, did not radically remake the Constitution into a guarantor of voting rights, even though this is routinely claimed. It is certainly true that the amendment’s opening line references such a right—“the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied”—but that mention is an illusion, having no fixed reference point in the Constitution, then or now. The United States is, in fact, one of the few constitutional democracies that extends no such right in its governing charter.

As centennial celebrations gear up around the Nineteenth Amendment, we will hear again and again about how women won the right to vote in 1920. It makes for a great story, full of drama and triumph. And it was a tremendous, historic victory that affirmed in various ways that women were, and should be, part of the body politic, at least in principle.

But the real story is considerably more complicated. Because states, and not the federal government, appoint voters, millions of women were already voting before 1920. And because what women technically won was only nondiscrimination in voting on the basis of “sex,” millions of women still could not vote after 1920. Given this, we cannot pinpoint a single date when women won the vote, reflecting just how localized voter governance is in the United States.

Subsequent to 1920, various court cases, federal laws, and two more constitutional amendments (barring poll taxes and lowering the voting age to 18) have continued to bar state-level disenfranchisement in significant ways, but none of those federal measures have yet assured Americans of a “right to vote.” Securing that perceived right, which the fights for both the Fifteenth and the Nineteenth amendments cleaved opened, remains the unfinished work of this hard-fought historical legacy.

About

Lisa Tetrault is associate professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University and author of The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898, which won the Organization of American Historians’ Mary Jurich Nickliss history book prize. In 2007, she received a fellowship at the Massachusetts Historical Society that was supported by an NEH grant.

Originally published as “Winning the Vote” in the Summer 2019 issue of Humanities magazine, a publication of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Sources

Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (Indiana University Press, 1998); Martha S. Jones, “The Politics of Black Womanhood, 1848–2008,” in Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence, Kate Lemay, ed. (Smithsonian Institution with Princeton University Press, 2019); Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (Basic Books, 2000); J. D. Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power (Oxford University Press, 2014); Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, ed., One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement (NewSage Press, 1995); Liette Gidlow, “The Sequel: The Fifteenth Amendment, the Nineteenth Amendment, and Southern Black Women’s Struggle to Vote, 1890s–1920s.” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (July 2018); Elaine Weiss, The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (Viking, 2018).