By Alison Parker

Expressing an early version of the theory of intersectionality at the turn-of-the-twentieth century, Mary Church Terrell identified herself as “a colored woman in a white world” who experienced both racism and sexism. Throughout her life, Terrell also publicly advocated on behalf of black girls and women who were unfairly convicted for defending themselves against assaults by whites. Today, black women activists have similar priorities. Kimberle Crenshaw’s African American Policy Forum, for instance, coined the hashtag movement #SayHerName, urging the Black Lives Matter movement to bring specific attention to police violence against black women such as Sandra Bland, Tanisha Anderson, and Breonna Taylor. They are also drawing attention to the fact that black women are being incarcerated at increasing and disproportionate rates. Unceasing Militant, my forthcoming biography of Mary Church Terrell, shares the life and priorities of a black feminist foremother whose voice was insistent, clear, and powerful.

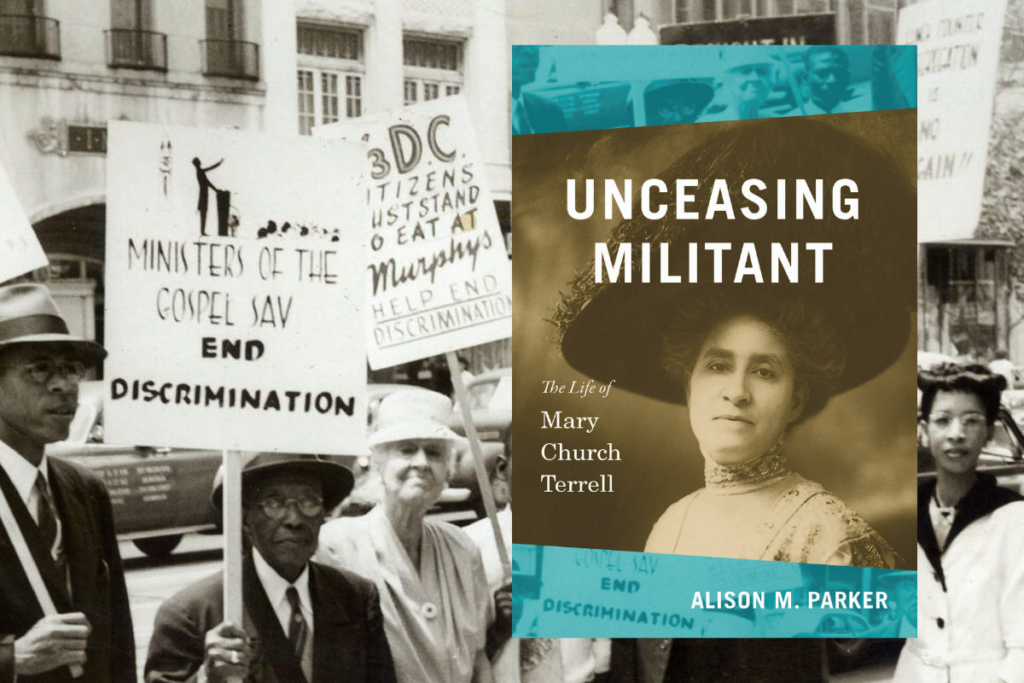

An exclusive excerpt from Unceasing Militant.

As she pursued voting rights, Terrell simultaneously engaged in a related effort to achieve equality by dismantling racist and sexist stereotypes about black women as sexually impure. The National Association of Colored Women had formed in 1896 in part to provide black women with a national platform from which to defend themselves against scurrilous slander by hostile whites. Such slander had become an excuse for dismissing concerns about sexual violence against black women.37

Determined to protect her own and all African American daughters from these racially prejudiced and gendered stereotypes as they grew into young womanhood, Terrell wrote and spoke explicitly about sexual purity. Her public speeches offered cogent critiques of racist caricatures that demonized black girls and women as impure, a stereotype that put them at increased risk of harm. White and black audiences and the newspapers reacted strongly to Terrell’s piercing analyses of how sexism and racism affected the lives of all African American girls and women who had to live and survive in a culture that assumed their racial and sexual impurity.38

When the white National Purity Association first invited Terrell to give a talk on “Purity and the Negro” in 1905, she noted in her diary that it “is not a subject one can treat easily, altho’ there is a great deal to be said.”39 Her first purity talk comprehensively laid out her fundamental black feminist ideas about the intersections of gender, race, and purity—ideas that shaped and were shaped by her experience of raising two African American daughters in a hostile, racist society. Terrell used her time at the lectern to dispute whites’ assumption that African Americans were innately more immoral and impure.40 Completely rejecting that premise, she began by criticizing whites for their racial bias: “Those who insist that colored people are brutes with respect to their sexual natures, as is often asserted by the enemies and traducers of the race, either ignore or maliciously misrepresent the facts.” Adroitly shifting the blame to white men, Terrell defended the honor of black women, reminding her audience that “during slavery it was impossible for bond-women to protect themselves from the lust of their masters, the sons of their masters or their masters’ friends.”41 Highlighting the vulnerability of black women to rape by white men, she insisted . . . that crimes against African American women must be taken as seriously as those against white women.

White male violence undermined the sanctified categories of home and womanhood: “In the South, the negro’s home is not considered sacred by the superior race. White men are neither punished for invading it, nor lynched for violating colored women and girls.” Condemning a double standard of sexual purity, she contended that until the day when rape was a crime no matter the race of the victim, black women would not be recognized as legitimate victims or full human beings. White men would continue to claim superiority while acting with impunity, whereas black men would be unfairly accused and even murdered for rapes they did not commit.43

Daring to shift the terms of the debate, Terrell moved from accusing white men to publicly charging white women with responsibility for perpetuating the problem of assaults against black girls and women. White women must openly protest the rape of black women by white men, she said, for only their voices could “arouse the conscience of the public toward the open and shameless debauchery of colored women by [white women’s] husbands, fathers and sons.” Instead of forming a sisterhood based on women’s collective resistance to sexual violence, Terrell pointed out that “the white women of the South who discuss the subject in the public print . . . seem to delight in exposing the weakness of colored women. . . . In several articles . . . in one of the best magazines . . . southern white women have declared . . . that there is no such thing as a virtuous colored woman in the United States.” White female authors used their access to national media to denigrate and further endanger black women by increasing race hatred, whereas most black writers did not have access to mainstream media.44

It was white women who had inherited immorality, Terrell countered, because of their callous indifference toward the rape of African American women: “Descended from generations of [white] mothers who were accustomed to look upon the wholesale debauchery of colored women without a protest and without the shock to their moral natures which they would be expected to receive, their daughters have inherited this indifference to the degradation of colored women by the men of the present day.” She bluntly told her white audience, “Morally speaking, slavery was a weapon which shot both ways, wounding those who fired as well as those who were hit. . . . Surely [white women] must know that so long as men may despoil the women of any race with impunity, this prevailing standard of morality must necessarily be very low.”45 …

A comprehensive and powerful defense of African American womanhood was at the core of all of Terrell’s speeches at white purity conventions. Every time she spoke honestly to white audiences, she took a significant risk. . . . When she spoke in 1907 “On the Condition of the Colored Woman” at the National Purity Conference in Battle Creek, Michigan, the press was ready to pounce. The Battle Creek Enquirer reported, “Negro Speaker Assails White Women of South.” The Associated Press, in a widely reprinted story, denounced Terrell’s “furious invective” and charged her with claiming that no black woman was safe working as a servant in a white household. This particularly alarmed the white press and its readers, who feared losing their cheap labor supply if African American women declined to do this work. . . .

Invited to speak at the 1911 World’s Purity Congress, in Columbus, Ohio, Terrell had not forgotten the backlash but decided to take the same hard-hitting approach. Afterward, she reported to Berto: “My darling Husband: . . . You should have heard that vociferous prolonged applause when I finished my address! . . . I tell you white people like to hear the disagreeable truth, if one has tact and good taste enough to present it forcibly but politely. I am amazed myself at the quantity of hard pummeling they are willing to stand from me.” She had again “poured it on to white women good and hard and strong.”48

Continuing her 1911 lecture tour, Terrell inspired African American audiences, too, with her blunt message about how racism had created distorted notions of purity. Her refusal to accept the fiction of black women’s innate impurity resonated with African Americans.

From Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell by Alison M. Parker. Copyright © 2020 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org.

Photo Above: Mary Church Terrell and others protesting lunch counter segregation, 1952. Courtesy Moorland-Springarn Research Center at Howard University.

Keep up with HNY —get the newsletter!

Alison M. Parker is Chair & Richards Professor of American History at the University of Delaware. She has research and teaching interests in U.S. women’s and gender history, African American history, and legal history. She majored in art history and history at the University of California, Berkeley and earned a PhD from the Johns Hopkins University. In 2017-2018, Parker was an Andrew W. Mellon Advanced Fellow at the James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference at Emory University. Parker is author of Articulating Rights: Nineteenth-Century American Women on Race, Reform, and the State (2010) and Purifying America: Women, Cultural Reform, and Pro-Censorship Activism, 1873-1933 (1997). Parker also serves as co-editor of the Gender and Race in American History book series for the University of Rochester Press. As Chair of the History Department at the University of Delaware, Parker is committed to helping to build a coalition of students, faculty, and staff promoting a wide-ranging anti-racism agenda.

Notes:

37. Rudolph, “Victoria Earle Matthews,” 106; Guy-Sheftall, Daughters of Sorrow, 26–27; Salem, To Better Our World, 20–22; Hine and Thompson, Shining Thread, 180.

38. Even after her father’s death, Mollie [her nickname] remained sensitive about his background as a saloon owner and developer of Beale Street. Berto reassured Mollie: “By all means attend the Social Purity Congress. Nobody is giving your father’s life a thought. He atoned for all of his sins by accumulating and leaving a fortune. You are entirely too sensitive about his career.” Preston Lauterbach argues that Church’s houses of prostitution were protected by white police officers and Memphis officials because he supplied white prostitutes to white men in a protected vice zone. There is no evidence that Mollie knew about this aspect of his business. Lauterbach, Beale Street Dynasty, 87, 113; RHT to MCT, November 6, 1913, MCT Additions; MCT, “What the Colored Woman’s League Will Do,” 155–56; MCT, “Lynching from a Negro’s Point of View,” North American Review, June 1904, 853–68; MCT, “Purity and the Negro,” 1905, MCT Papers, reel 2 (published in the Light, June 1905, 19–25).

39. In the Light (1905), Terrell was described as “one of the principal speakers at the Conference, her message is always in behalf of the colored people. Herself a colored woman, she can plead the cause of this struggling race with deep earnestness and feeling and we prophesy that there will not be a dry eye nor a cold heart in the audience.” In advance of the 1927 International Purity Conference, it described her as “probably the most eloquent Negro Woman on the American platform. . . . She is a former member of the school board in Washington and is a high official of the International Council of Women of the Darker Races.” That year, Terrell served on a Joint Committee on Delinquency and Crime in Washington, D.C., which noted that “colored girls are arrested and placed in jail more quickly than white girls and an investigation along this line was suggested.” “Notes on Meeting, Joint Committee on Delinquency and Crime,” 1927 and undated, MCT Papers, reel 15. “National Purity Conference,” La Crosse, Wis., October 17–19, 1905; the Light gives detailed information about the speakers on the Purity Conference programs as well as National and International Purity Congresses, 1905, 1907, 1913, 1927, and undated, MCT Papers, reel 16; MCT Diary, September 17, 22, 1905, MCT Papers, reel 1.

40. For more on white purity organizations, see Foster, Moral Reconstruction, 140–43. For its investigations of prostitution, see Rosen, Lost Sisterhood, 14; Satter, Each Mind, 208–9.

41. In a 1905 Voice of the Negro article, Fannie Barrier Williams similarly pointed out that “the women of other races bask in the clear sunlight of man’s chivalry, admiration, and even worship, while the colored woman abides in the shadow of his contempt, mistrust or indifference.” Fannie Barrier Williams, “The Colored Girl,” Voice of the Negro, June 1905, 400–401, quoted in Guy-Sheftall, Daughters of Sorrow, 90, n. 167, 195; James, “Shadowboxing,” 349; MCT, “Purity and the Negro.”

43. See Collins, Black Sexual Politics, 217; Perkins and Stephens, “Introduction,” 5; Hall, Revolt against Chivalry; Wells-Barnett, Southern Horrors, 49–72; Feimster, Southern Horrors, 97–92; Freedman, Redefining Rape, 73–88; Rosen, Terror, 9–11; White, Dark Continent, 33; Kuhl, “Countable Bodies,” 133–60; and Terrell, “Lynching from a Negro’s Point of View,” North American Review, June 1904, 853–65.

44. Similarly, in the YWCA, Addie Hunton “and her colleagues sought to persuade white women that they (white women) had a Christian duty to improve race relations.” Robertson, Christian Sisterhood, 26; Dunlap, “Reform of Rape Laws,” 352–72; Shaw, What a Woman, 197, 210; Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow, chap. 6; MCT, “Purity and the Negro.”

45. Educator Charlotte Hawkins Brown made a similar point in 1920: “We have begun to feel that you are not, after all, interested in us. . . . The Negro women of the South lay everything that happens to members of her race at the door of the Southern white woman.” Brown quoted in Laville, Organized White Women, 43; MCT, “Purity and the Negro.”

48. When she spoke to white women in Wilmington, Del., for instance, Terrell challenged them: “Did you ever feel, sisters of Wilmington, that you are to a certain extent responsible for the downfall . . . of these girls[?] . . . .Did it ever occur to you, good people, how many and how great are the temptations to which colored girls are subjected in various sections of the country? They are marked as the legitimate prey for the evil minded of all races and complexions.” MCT to RHT, October 27, 1911, MCT Papers, reel 2; MCT, “Address to Raise Funds for a Home for Delinquent Girls” (undated), MCT Papers, reel 23.