In the summer of 1964, about a thousand young Americans, black and white, came together in Mississippi to place themselves in the path of white supremacist power and violence. They issued a bold pro-democracy challenge to the nation and the Democratic Party. This week Amended host Laura Free introduces “Freedom Summer,” a special episode from a podcast called Scene on Radio, one of the sources of inspiration for Amended. Season 4 of Scene on Radio was called “The Land that Never Was,” which looks at the nation’s history from its beginnings to the present to understand the deep-rooted challenges that American democracy has never solved. “Freedom Summer” highlights an important chapter in the struggle for equal voting rights.

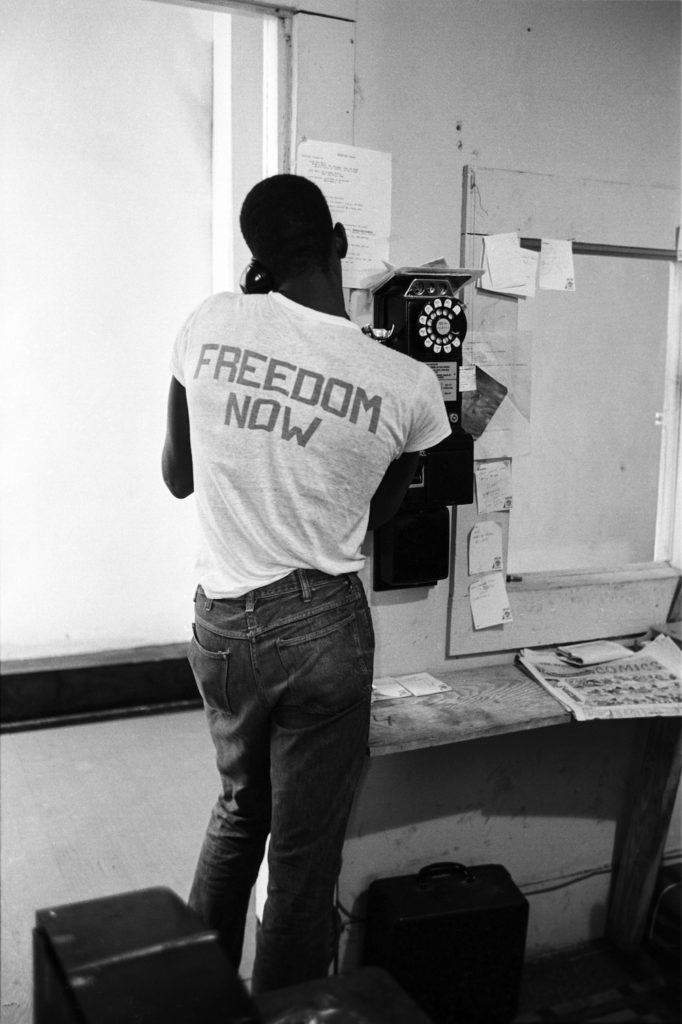

Photo: A Freedom Summer worker in Mississippi, 1964. Photo by Steve Schapiro.

[Music]

Laura Free: Hi everyone, this is Laura Free, host of Amended, a podcast from Humanities New York. The next and final episode of our series is coming out next week, but today we have a special bonus episode for you.

[Music Change]

Laura Free: When our team set out to make Amended, one of our inspirations was a podcast called Scene on Radio. Season 4 of Scene on Radio was called “The Land that Never Was,” and it looked at the nation’s history from its beginnings to the present to understand the deep-rooted challenges that American democracy has never solved. What you’re about to hear is an incredibly moving episode called “Freedom Summer.” It’s about the summer of 1964. Almost 100 years earlier, the 15th Amendment was passed to prevent voter discrimination based on race. This was followed in 1920 by the 19th Amendment, which was supposed to do the same for women. But as we’ve discussed on this show, these were incomplete victories. The states invented other means, like poll taxes and literacy tests, to disenfranchise Black, Southern voters. For generations, activists rose up to fight these discriminatory laws. And in 1964 things reached a boiling point. About a thousand young Americans, Black and white, led a campaign in Mississippi where they registered Black voters and trained emerging activists in how to challenge the racist political system. When they did this, the activists put themselves directly in the path of white supremacist violence, sacrificing their safety and in some cases their lives. Their actions forced the federal government to admit that the Constitution, as written, was still allowing unchecked voter discrimination, and then to finally do something about it. Now here’s the hosts of Scene on Radio, John Biewen and Chenjerai Kumanyika. Please note that the “Freedom Summer” episode was originally released about a year ago, so you’ll hear a few references to the early days of the pandemic and to the 2020 elections.

John Biewen: A content warning: this episode includes descriptions of intense violence, and the use of a racial slur.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: So John, when you look at history the way that we’re looking at it in this series, sometimes I start to get tempted to make really sloppy historical comparisons. You know what I mean? ‘Cause that’s easy to do.

John Biewen: It is easy to do. What’s that expression: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does often rhyme. And it’s easy to get carried away trying to hear those rhymes.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: In the scholarly world, we learn to have nuance and not to do that, but, you know, sometimes, I myself have been guilty. I worked on this podcast, Uncivil, about the Civil War, and during that time I was like, everything is just like 1861. I would be at dinner parties and people are like Chenj, we get it, to understand anything, like a movie–we have to go back to the 19th century, we understand.

John Biewen: Yeah. Or, you know, the United States today is Germany 1933! Right? Well, maybe it is, somedays it seems to be, but yeah, you try not to get too carried away reading the newspaper every morning.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Absolutely. That said, I do think it’s really important to think about the themes and continuities and lessons that we can really learn from history. And today’s episode has me thinking about political parties, and this kinda never-ending struggle that they have between what gets called party “unity,” or maintaining a “big tent,” and then on the other hand really trying to stick to or imagine more ambitious or even radical policy positions that vulnerable groups within the base of the party care about.

John Biewen: Yeah. Both major parties in the U.S. have this struggle – really all the time, to some extent — but then sometimes the tension gets more cranked up than at other times. And as we’re talking here in 2020 there’s an intense struggle within the Democratic Party in particular. Do you reach toward the middle or even to the right to form a coalition with people who only kinda sorta agree with you on some things … or do you push — in the case of Democrats — a more sharply progressive agenda? Maybe because you think that’s the winning strategy, or because you just don’t want to make all those compromises.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: And I mean, to me it just always seems like looking at the Democratic Party, there’s always a faction pulling it in the wrong direction in history. So for example think of the Democratic Party of the 1960s, what we’re going to talk about. It had changed a lot since the 1860s when it was the proslavery, pro-secession party. After the New Deal and liberal policies under Truman and Kennedy, now it’s the political home of most working class people. The Democratic Party is where most working class people of every race and identity, including Black people, are. But you still got this coalition that includes all these elected politicians down in the South where one-party, apartheid, Jim Crow politics are still explicitly in force.

John Biewen: And leaders of the Democratic party, the national party, still think they have to answer to those people in order to keep this coalition together and this is incredibly frustrating to Black people, especially Black people living in those southern states.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Yeah. So like that’s the tension. You see it then. And I think today, right, a lot of Democrats think of the choice as one between a status quo that they’re kind of used to, and maybe it’s not perfect, or some other authoritarian republican monster. But what I think they forget is that for some groups, the status quo, the idea of normal, is totally unacceptable for people. And even deadly. It also was like that in 1964. That’s what makes it interesting for me. What they were facing was brutal repression. And they just felt like the stubbornness and these incremental arguments were coming at the cost of their lives. I mean, just going back to there, it was really very intense. I almost wish we could hear from somebody who lived through that time.

John Biewen: Ooh. Well, let’s see, actually I think I may have an old piece of audio tape lying around here somewhere. Check this out:

John Biewen: Check, one, two. Mr. John Lewis. Were you involved in the discussions about whether to do the summer project, to invite in northerners?

John Lewis: Well, at the time of the planning for the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964, I was the national chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. So I was involved. . .

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Okay, just to make this clear. That’s you, and then a younger John Lewis, more than 25 years ago, in 1994.

John Biewen: That’s right. Yep.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: You were making a documentary about this plan to force the Democratic party to kind of address it’s own sh**.

John Biewen: Yes. So, 1994, and I’m making a documentary about 1964, and what came to be called Freedom Summer. Of course, a lot of people have heard that term, but I think a lot of people may not know a lot about what happened that summer. And of course now, we’re coming up on sixty years since Freedom Summer. So it feels lucky I was able to talk to a bunch of the people involved back then because some of those folks are no longer with us. Though many still are, thankfully. But I interviewed a few dozen people who took part in this really pretty radical organizing effort in ’64.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: So in 1964 you have America still calling itself a democracy, but all the way after, you know, the 15th amendment and all these other things, right, the Democratic party in Mississippi and other places won’t even let Black folks vote, much less participate as elected officials. And the national party really isn’t doing anything.

John Biewen: Yeah. Not only was the party not doing much to stand up for the political rights of Black people, it was literally not protecting them from widespread racist violence. Especially in places like Mississippi.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: So what do people leading the civil rights movement in Mississippi do? They come up with a plan that is really innovative and creative but extremely dangerous. But it’s a plan to force the Democratic Party to stop having it both ways and to choose a side once and for all.

[Music: Theme]

John Biewen: From the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, this is Scene on Radio Season Four – Episode 7 in our series on democracy in America. We call the series The Land That Never Has Been Yet. I’m John Biewen, producer and host of the show. Dr. Chenjerai Kumanyika, whose voice you were just hearing, is my collaborator on the series. He’s a Journalism and Media Studies Professor at Rutgers, an artist, podcaster, organizer, pie chef, and baker of zucchini bread. He’ll be back again later to help me sort things out. This episode: 1964. Mississippi, and really, the USA. We took apart the radio documentary I made in the nineties, and updated and rebuilt it for this season using the interviews that my co-producer Kate Cavett and I recorded back then. Deep into the twentieth century, the struggle was still very much on for something resembling a multiracial democracy in the U.S. A struggle led by Black Americans, and their accomplices of all shades. What did those young people accomplish that summer? And, in what they failed to achieve, what hard truths about the United States did they uncover yet again?

[Music: Get on Board, Children, Children…]

John Biewen: Nobody called it Freedom Summer until after it was over. To the people who organized it, it was just the Mississippi Summer Project. About a thousand mostly young Americans, Black and white, came together to place themselves in the path of white supremacist power and violence. Lawrence Guyot was on the staff of SNCC, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the lead organization behind the project.

Lawrence Guyot: The ’64 Summer Project was the most creative, concentrated, multi-layered attack on oppression in this country. There’s nothing to compare with it. Because you brought in different people with different talents for different reasons. And there was a sustained fight. And there was no middle ground. You were either for change or you opposed change.

[Music]

John Biewen: In the early 1960’s, white Mississippi held most of its Black residents in a kind of serfdom. Many worked on cotton farms, like their enslaved ancestors – legally free to come and go but with no real options for making a living. Sharecropping and tenant farming arrangements paid subsistence wages, if that. Public education was separate and deeply unequal – the state, which spent less on education than any other, funded Black schools at a fraction of what it spent on white schools.

Unita Blackwell: I guess I was born in it, you know. I was born in the movement, the day I was born I was born Black.

John Biewen: Unita Blackwell was born in 1933. She lived all her life near the Mississippi river, in Mayersville.

Unita Blackwell: So all my life I knew something was wrong with the way that people perceived me as a Black person, ’cause I was born in the Mississippi Delta.

John Biewen: Until 1961, people doing civil rights organizing in Mississippi did it in secret. That’s how dangerous it was.

John Lewis: I grew up in rural Alabama, about fifty miles from Montgomery, near a little place called Troy. So I had seen segregation and racial discrimination. My own mother and my own father could not register to vote.

John Biewen: John Lewis said he first went to Mississippi as a Freedom Rider, at age twenty-one.

John Lewis: You know, in spite of growing up in Alabama, where it’s not too much different, but Mississippi! It was just, this was the last place. When you crossed that state line from Alabama to Mississippi, there’s just this sense of something like, the climate changed, the air got warmer and your heart started beating faster. You was in a different place. Where too many people had died, too many bodies had been found, Black bodies, in the Pearl River or the Tallahatchie River, in the state of Mississippi.

John Biewen: Starting in 1961, a few young staff members with SNCC ventured into the state. They began coaxing Black people to go to their county courthouse to try to register to vote. The system designed back in 1890 to prevent Black people from voting was still in place. State laws gave county registrars, all of them white, discretion to decide who could become a registered voter, based on a literacy test that the registrars could easily manipulate. They often approved illiterate white people and rejected almost all Black people regardless of their actual literacy. When Unita Blackwell and a few other local Black folks went to register in Mayersville, a white mob met them at the courthouse.

Unita Blackwell: So that courthouse, that we wasn’t allowed to go in, unless it was time to go over there and pay your tax or something like that, and you went in the back door. So we was to go to that side, back, to try to get in. And the look on the whites’ faces, they were just red, you know, and the anger and the hate. And we stood there. And I got very angry that day, and determined, or something happened to me. And I decided nothing from nothin leaves nothin. ’Cause we didn’t have nothin. And you were gonna die anyway. Because they’re standin there with guns and you hadn’t done nothin. So I went to try to register to vote.

John Biewen: Ms. Blackwell was turned away without being physically attacked. But some Black people who tried to register in the state were beaten, jailed, even murdered. In June of 1963, an avowed racist named Byron de la Beckwith fired a single bullet through the heart of Medgar Evers, Mississippi leader of the NAACP, as Evers walked into his house in Jackson. Evers was a World War II veteran and the father of three young children. For white Americans in deep, willful denial about systemic white supremacy, here was another wake-up call. The national leader of the NAACP, Roy Wilkins, at a press conference.

Roy Wilkins: We view this as a cold, brutal, deliberate killing in a savage, uncivilized state. The most savage, the most uncivilized state in the entire fifty states.

Bob Moses: When Medgar was assassinated, it focused a lot of national attention on Mississippi, and various individuals and groups were considering doing something.

John Biewen: The leader of SNCC’s efforts in Mississippi was Bob Moses. He was just twenty-nine in 1964 but that made him older than most members of SNCC. Moses grew up in Harlem. He’d earned a master’s degree in philosophy from Harvard, and he was known for being thoughtful and soft-spoken as well as courageous. He led those early efforts to register Black voters in Mississippi. He’d been beaten badly and survived a sniper attack. Moses said it was the assassination of Evers that drew the involvement of key white collaborators: Allard Lowenstein, a political activist from New Jersey who would later serve a term in Congress. And Robert Spike, who led a commission on race for the National Council of Churches.

Bob Moses: ‘Cause certainly Al’s recruitment, through his whole network, of white students across the country, and then Spike’s support, through the National Council of Churches, were two critical ingredients in the whole idea of sort of having the country take a look at, first hand, Mississippi.

[Music: This Little Light of Mine]

John Biewen: In the fall of 1963, Moses and his collaborators proposed a massive project for the following summer. The centerpiece was a plan to launch an alternative political party as a challenge to Mississippi’s closed, racist, one party system. The organizers planned to invite up to a thousand mostly-white volunteers from northern universities to help with the project, and to try to register Black voters. The plan to bring in a lot of white students raised controversy inside the movement. SNCC was founded in 1960 under the leadership of Civil Rights Activist Ella Baker. It was an outgrowth of the student lunch counter sit-ins in places like Nashville, Tennessee and Greensboro, North Carolina. Its leaders were Black, but SNCC was consciously integrated; it had a few white staff members from its beginnings. Still, for the mostly-Black SNCC staff in Mississippi, the proposed infusion of white volunteers led to sharp debate.

Hollis Watkins: I was opposed to the idea of bringing in massive numbers of people from the north.

John Biewen: Hollis Watkins grew up in Lincoln County, Mississippi. He was one of the first in the state to join SNCC, in 1961, when he was nineteen. Hollis said what he cared most about was the painstaking work that civil rights workers were doing with Black Mississippians themselves.

Hollis Watkins: I saw people who had began to take initiative for themselves, and acting on those decisions that they made. And to me, this was growth. And deep down within I felt that young people coming from the north, who for the most part perhaps felt that they were better than we from the south, who felt that they had to be on the fast track to get certain things done because they would only be here for a short period of time, I felt that these people would overshadow the efforts of the people from Mississippi, and would retard that development and growth that had already began to take place.

John Biewen: What was your response to that argument?

John Lewis: Mine was very simple….

John Biewen: John Lewis, then the national chair of SNCC, understood the concern raised by Hollis Watkins and others. But he thought the summer project was a risk worth taking.

John Lewis: We had an opportunity to educate America. It would demonstrate that we could build a truly interracial democracy in America, to have young, local, primarily poor Blacks working with primarily middleclass white students from the north, side by side. It was something I think that we had to try. We hadn’t been down that road before.

Bob Moses: Either way, I mean it was damned if you do and damned if you don’t, that’s all. But that was Mississippi.

John Biewen: Bob Moses and the rest of the SNCC staff in Mississippi continued this debate into early 1964. When one more death of a Black man tipped the scales.

[Sound: Allens’ yard.. birds, neighbors’ voices in distance]

Henry Allen: That time of year, up in that part of the country, like January? Lot of people do night hunting and stuff up there, so it’s not unusual to hear gunshots in January at night. And we lived a little ways off the road, too, you know?

John Biewen: Henry Allen was 18 years old in early 1964, when someone came for his father, Lewis, at their place outside of Liberty, Mississippi. Lewis Allen was a logger and farmer. He’d been a witness two years earlier when another Black farmer, Herbert Lee, was murdered for trying to register Black voters. So, first, the Herbert Lee story: A white state representative, E.H. Hurst, confronted Lee in the fall of 1961. Lee and Hurst were neighbors, and they’d been childhood friends, but Lee had stepped out of his place. He’d started working with members of SNCC on voter registration efforts, and that infuriated E.H. Hurst. They argued that day, and Hurst shot Lee in the head in front of more than a dozen people, including Lewis Allen. Hurst told police Lee had threatened him, so he’d shot him in self-defense. The Black witnesses, including Lewis Allen, went along with that story, knowing what could happen to a Black person who testified against a white man in Mississippi. But later, Lewis Allen quietly told a few people that the self-defense story was a lie; Hurst had shot Lee with no provocation. Allen did not testify against Hurst, but word spread that he’d spoken the truth about the murder, and local police and other white men started harassing and threatening him. Civil Rights Activists told the FBI that Lewis Allen was in danger, but the agency did not protect him. On a January night, his son Henry came home from a date and found Lewis in the front yard.

Henry Allen: Oh, he was just mutilated. I meant, to shoot a person in the head with a shotgun at close range, I meant, just chaos, man. Just chaos, you know. Yeah, I never wanted my mama or my little sister to ever see him. My mama wanted to go down that road but she’d of stroked out, she’d’ve probably died right there. Just too much to look at, somebody that close to you. ‘Cause we was close people, you know?

John Biewen: No one was ever charged with the murder. Bob Moses and other members of the SNCC staff were in Hattiesburg, discussing whether to go ahead with the summer project, when the news came. Bob Moses: Yeah, it came down, it was my decision to move it. And what moved me was Lewis’s murder, that was it. I decided that what was important for us in Mississippi was to see if we could break the back of the state, politically.

[Music]

John Biewen: A civil rights coalition, led by SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, announced plans for what would come to be called Freedom Summer — a peaceful program to bring democracy to Mississippi. Besides college students and teachers, several hundred lawyers, medical professionals and clergy would descend on the state. White Mississippi politicians, and many of the state’s white journalists, denounced what they called an ’invasion’ by ‘outside agitators.’ Police departments hired more officers and bought riot gear. The Ku Klux Klan and another racist group, the White Citizens Council, issued threats. In June, hundreds of mostly-white northern college students gathered in Oxford, Ohio, for week-long training sessions sponsored by the National Council of Churches. Hollis Watkins: We had to tell these young people exactly what they were getting ready to get involved in. And we had to be truthful with them….

John Biewen: Hollis Watkins helped with the training of the northern volunteers.

Hollis Watkins: If they were coming to Mississippi, they had to be prepared for at least three things. They had to be prepared to go to jail, they had to be prepared to be beaten, and they had to be prepared to be killed. And if they were not prepared for either one or all three of those, then they probably should reconsider coming to Mississippi.

John Biewen: SNCC and CORE staff lectured the white students on voterregistration techniques and non-violent philosophy. Bob Zellner, a white SNCC staff member from Alabama, remembers the volunteers were also given rules for survival in the segregated South.

Bob Zellner: No interracial groups travelling, day or night, unless absolutely necessary. And if that happened, only one, whoever was in the minority, would be hidden, covered up with blankets, laying on the floor boards, whatever. Training in jail procedures. If you’re released from jail at odd hours, and so forth, there’s not somebody there, refuse to leave. People had done that before and disappeared, been killed, people who did that afterwards disappeared, and so forth.

John Biewen: The training sessions foreshadowed the violence that would come, but also the racial and cultural gaps among the summer project workers. Some African American SNCC staff members were traumatized and angry after several years in what felt like a war zone. They saw the white students as naive idealists off on a summer adventure. Robbie Osman was a 19-year-old volunteer from New York City. He remembered the tension burst open one day, during the training in Ohio, when SNCC staff members showed a film clip: a Mississippi registrar turning away Black people trying to become voters.

Robbie Osman: Someone had tried to register and he was sending them back and being vaguely threatening and it seemed to us, the young white college students, that this guy was as ridiculous, as pathetic, as caricature a racist as we ever expected to see. And we laughed. And to our complete surprise — I speak for myself, I really didn’t expect it — this horrified the SNCC veterans. Folks stood up and said, ‘How can we go to Mississippi with you? How can we put our lives on the line with you guys? You really don’t have a clue as to what’s going on, do you? You really don’t know what this guy represents in the context in which he really lives.’ And I think it was a moment in which we all had to stop and realize the gap between us. If we were to reach across it, it was gonna take a lot of reaching.

[Music]

John Biewen: On June 21st, the day after the first northern volunteers arrived in Mississippi, three young civil rights workers disappeared after being pulled over by a sheriff’s deputy near the small town of Philadelphia. One of the men was James Chaney, a 21-year-old Black Mississippian and a staff member with CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. His mother, Fanny Lee Chaney, was interviewed in 1965.

Fanny Lee Chaney: Well I knew it was something had happened to my child, because I didn’t care where he went … he would always call me and say ‘I’ll be there at such and such a time, Mommy, I’m on my way,’ or something like that. But all that Monday and that Sunday night, I just knew it was something wrong, he was somewhere where he couldn’t get in touch with me.

John Biewen: Unlike Herbert Lee and Lewis Allen, and other Black Mississippians whose murders went unreported outside the state, James Chaney was traveling with two young white men from New York: fellow CORE staff member Michael Schwerner, and summer volunteer Andrew Goodman. The federal response this time led Mississippi Governor Paul Johnson to hold a press conference.

Governor Paul Johnson, Jr.: President Johnson has ordered 200 Marines and eight helicopters to join in the search for three civil rights workers missing in Mississippi. Their presence here is indeed a surprise to me….

John Biewen: The bodies of the three young men were found six weeks later, buried under a red-clay dam. Mississippi authorities failed to indict anyone for the killings. The federal government eventually convicted seven white men, in 1967, including Neshoba county sheriff’s deputy Cecil Price. None of those men served more than six years in prison. Another Klan leader involved in the murders, Edgar Ray Killen, was convicted forty-one years later, in 2005. He died in prison in 2018.

[Music]

John Biewen: The nation’s response to the killing of white civil rights workers drove home a central point of Freedom Summer. Volunteer Robbie Osman told me that for the first time, he really grasped the double standard that valued white lives more than Black lives — a double standard not just in the South, but embedded in U.S. culture. Robbie Osman: The very reason that we were there as white college students was that unless the country’s attention was focused by the presence of those people that this country was accustomed to caring about, namely white college students, nothing would happen. And if it was only people who this country was not accustomed to caring about, namely Black Mississippians, then nothing would happen. And I think that what embarrasses me is the extent to which I was capable of forgetting or underestimating that. It’s not that I didn’t know it, it’s that I didn’t feel it.

[Sound: crickets, cars…]

Unita Blackwell: You would look out there and the highway patrol would be sitting there in the white, and police would be right here, and they would always be. ‘Cause this was the corner, you know, where I lived…

John Biewen: During the summer of 1964, Unita Blackwell’s home became a focal point for civil rights activity. As project director for Issaquena County, in the Delta, Blackwell had summer volunteers sleep on the floor of her two-room house, and she oversaw the county’s voter registration efforts.

Unita Blackwell: ’Cause it was our daily operation. It wasn’t like you was at home, get up and clean up your house and do a meal and sit around and talk to people or go to work or something. This was it. You ate, you slept, you did everything in terms of voter registration.

[Music]

John Biewen: Volunteer Joe Morse of Minnesota and Mississippian Rosie Head were among those who spent the summer looking for potential Black voters, and members for the new Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Joe Morse: So it meant going door to door. Usually we were in pairs, well, we were always in pairs, usually a Black person and a white person…

Rosie Head: We would go from house to house and talk to people and try to encourage them to come out to meetings and explain to them how they could get registered to vote and what good it would do them if they could get registered.

Joe Morse: There’d be a home on the side of the road and you’d have to park your car and you knew that if anybody came by while you were parked there, if it was anybody related to the Klan or the White Citizens Council or some racist, they’d know your car and they’d know your license plate so you’re immediately putting the people you were talking to at risk.

Rosie Head: A lot of time we would get put out of people’s houses, they wouldn’t let you past the gate or they’ll just say they didn’t wanna talk to us, they didn’t wanna be involved in the mess, and they would just be afraid to talk to us.

John Biewen: On the surface, the voter registration drive failed. Out of half a million Black Mississippians of voting age, fewer than two thousand were approved as voters during Freedom Summer. But that was expected. The point was to show the country how the state systematically disenfranchised Black voters. At the same time, though, a lot more Black people signed up for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which would soon make history at the Democratic National Convention.

[BREAK]

John Biewen: The voter registration drive during Freedom Summer had another purpose, besides shining a light on the disenfranchisement of Black people. It also showed the nation how white people behaved when Black Mississippians tried to assert their rights as citizens. For several years, civil rights workers in the state had asked the federal government for protection, with no success. Michael Sayer was a young white man from New York and a staff member with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. He recalls that the FBI, under director J. Edgar Hoover, was well aware of Klan violence against Black Mississippians — in fact, the FBI had informants inside the Klan.

Michael Sayer: But the FBI policy wasn’t to intervene and prevent the Klan from doing what it was doing, it was simply to report back to the FBI so the FBI could be on top of the knowledge game. But we’re talking about J. Edgar Hoover here, who was very hostile to the idea of independent Black political activity.

John Biewen: During Freedom Summer, under pressure from President Johnson, the FBI opened an office in Jackson. But that didn’t stop the abuse or the terrorism. Mississippi police arrested more than a thousand civil rights workers during the summer. White supremacists burned down more than sixty Black churches and homes, beat up eighty civil rights workers, and fired dozens of shots into the cars and offices of Freedom Summer workers.

Dean Zimmerman: You came to see white faces as something to fear.

John Biewen: Dean Zimmerman was a white volunteer from North Dakota.

Dean Zimmerman: And of course, then you come to realize that this is the reality of Blacks every day of their lives, especially in that situation. That as you encounter a white face, you immediately, your body takes on a whole different posture, your mind becomes very alert. You are constantly on the lookout for what you may have to do in a big hurry just to survive.

Dorie Ladner: Fear was there. But I must say, it did not stop anything. I can’t recall anyone saying that I’m afraid and I’m not going to do it.

John Biewen: Dorie Ladner was a Mississippian, already a veteran SNCC staff member by 1964, when she turned twenty-two. During Freedom Summer she was project director at SNCC’s office in Natchez, where, she says, she spent sleepless nights taking threatening phone calls from white supremacists.

Dorie Ladner: I suffered from trying to dodge white men in pickup trucks, worrying about whether or not somebody was going to come and bomb the house where we were sleeping, whether or not we were gonna get killed, and I don’t like to ride in front seats of cars right now because I couldn’t drive during that time and I was always afraid of a drive-by shooting. Those were my problems.

John Biewen: Ladner told us the stress was so great, she vomited most nights after eating dinner. For some civil rights workers, the fears came horribly true. Matt Suarez was on the staff of the Congress of Racial Equality. He remembers, one night, someone made the mistake of bringing a white volunteer to an organizing meeting in the town of Canton, just outside of Jackson.

Matt Suarez: We had certain areas where we knew that if a Black guy and a white woman were seen together, it was almost certain death. At that time, Canton, Mississippi was one of those places.

John Biewen: Word got out that a white woman was in the meeting with Black men, and a white mob, including men from the sheriff’s department, gathered outside. CORE staff members decided to send out several Black men in one car to draw the mob away, and then sneak the white woman out in another car. Matt Suarez and another CORE staff member rode in the decoy vehicle with George Raymond, who was a leader of CORE in Mississippi.

Matt Suarez: And about fifty pickup trucks got behind us with white boys hanging off the running boards with chains and pipes and baseball bats and they screaming ‘kill the niggers’ and all this crap. And a highway patrolman and a sheriff’s deputy, and you have to understand this is a two lane highway, one lane in each direction, they got in both lanes following us and put their bright lights on behind us. And I told George, I said, ’hit em, George.’ He said, ’we can’t…’ And I said ‘George, this is no time to be stopping out here in the middle of nowhere. Hit em.’ George pulled the car on the goddamn side. They took George out, they had him behind the car, right in the headlights, so that all we could see was silhouettes, and they just beat George into the ground. They literally just pulverized him out there on the highway. The highway patrolman came over to us and he says, ‘You got twenty-four hours to get your Black asses out of Mississippi. If we ever catch you in here again we’ll kill you.’ And that ended that. They turned around and took off and we went and picked up George off the highway, put him in the car, and drove into Jackson. But you can’t imagine the fear that’s gripping you at that time that that’s happenin’, that you know they there, they wanna kill you, they can do it, there’s nothing to stop ‘em. And that stuff stays with you a long time. A long time.

[Music: Been in the Storm So Long]

John Biewen: George Raymond survived that beating, and several others he got in Mississippi jails. But his fellow civil rights workers say he changed from a light-hearted young man to a tense, bitter one. And he died of a heart attack in 1973. He was thirty years old.

John Biewen: The primary organizers of the southern civil rights movement did not meet in offices in Atlanta or Washington, D.C, or New York. They gathered at night, usually in Black churches, in small towns and on rural backroads, to form strategy and gain strength from one another. Music was a source of healing, unity, and motivation.

[Music: “O Freedom…”]

John Biewen: In this 1963 recording, Hollis Watkins, the SNCC staff member we heard from earlier, led the singing at a civil rights meeting in Jackson. In our interview in 1994, Hollis explained that most of the Freedom Songs were adapted from gospel, blues, and folk music, as tools for movement organizing.

Hollis Watkins: In the mass meetings you wanted to raise the interest, you wanted to raise the spirit, and in doing that it coincided with what would be going on in your daily activities. (Sings:) Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me ’round, turn me round, turn me round. Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me round, I’m gonna keep on walkin, keep on talking, fightin for my equal rights. Or you would say (sings:), marchin’ down the freedom lane. And as you sang the different songs, getting the spirit and the momentum going, you could eventually get to the song where you sang the question that kind of locked people in, you know, and… (sings:) Will you register and vote? Certainly, Lord. Will you register and vote? Certainly, Lord. Will you register and vote? Certainly, Lord. Certainly, certainly, certainly, Lord. Will you march downtown?…’

[Singing fades under]

Hollis Watkins: The late Fanny Lou Hamer, she was good about that. After we get people to singing certain songs, and if they made certain commitments in songs then she would hold them to that after the meeting and everything…

Fanny Lou Hamer, archival audio: And we can protest against these things by registering to vote! I want to know RIGHT NOW, how many people will go down Monday morning? If you afraid, me and my God’ll go with you!

John Biewen: Fanny Lou Hamer was a potent voice in the Mississippi Civil Rights movement. In 1962, after being recruited by SNCC activists, she went to the county courthouse in Indianola to register to vote. As a result, the white owner of the plantation where her family worked as sharecroppers evicted them. A couple of weeks later, night riders shot sixteen bullets into a house where they thought the Hamers were staying, but they weren’t there. The following year Mrs. Hamer was severely beaten in a Winona, Mississippi jail, after several people she was with used the whites-only restroom and lunch counter at a bus station.

Euvester Simpson: I was in jail with Mrs. Hamer in Winona.

John Biewen: Euvester Simpson was a 17-year-old activist at the time. Euvester Simpson: I remember I really was not afraid, I was more angry than anything because I shared a cell with Miss Hamer, and I remember we, I sat up at night with her, applying cold towels and things to her face and her hands trying to get her fever down and to help some of the pain go away….

[Music: Fanny Lou Hamer singing Walk with Me Lord]

Euvester Simpson: And the only thing that got us through that was that, we were all in these cells right along a wall, and we sang. We sang all night. I mean songs got us through so many things, and without that music I think many of us would have just lost our minds or lost our way completely.

[Fanny Lou Hamer singing]

John Biewen: From June through August, 1964, Freedom Summer organizers tried to bring America to Mississippi. At the end of the summer, organizers got ready to place the reality of Mississippi before the country’s largest political party, to test that party’s commitment to democracy. And Fanny Lou Hamer was about to take her turn on the national stage. White registrars had mostly blocked Black Mississippians from registering to vote during the summer. But alongside that effort, organizers had also created that new political party, the Mississippi Freedom Democrats. White registrars had no say in who could join this party. So, by August, the Freedom Democrats had signed up sixty thousand Black members and a few white ones. It was an open, democratic contrast to the state’s regular Democratic party, which excluded Black people and ran Mississippi’s white supremacist society. Lawrence Guyot was the new party’s chairman.

Lawrence Guyot: We paralleled the state organization of Mississippi where we could, where it was possible to do so and remain alive. We had our registration form, we conducted precinct meetings, we conducted convention meetings, we conducted county meetings and congressional district meetings, we elected a delegation. We then put that delegation on the way to Atlantic City.

[Music, Fanny Lou Hamer: Go Tell It On The Mountain]

John Biewen: In August, at its national convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, the Democratic party was set to nominate President Lyndon Johnson for another term. The Democrats wanted what major parties always want at their conventions: unity, and as little controversy as possible. But the Mississippi Freedom Democrats, the MFDP, got in buses and headed for Atlantic City – sixty-four Black people and four whites, some of them, John Lewis remembers, leaving Mississippi for the first time in their lives.

John Lewis: And we went to the Democratic convention, hoping and dreaming that this interracial party, this biracial party, will be seated as the official Democratic party of Mississippi.

John Biewen: Speaking to the party’s credentials committee on the first days of the convention, the Freedom Democrats said that unlike the all-white party, they had followed the party’s rules: Only their party was open to everyone. So only their delegates had been properly elected.

Fanny Lou Hamer: My name is Mrs. Fanny Lou Hamer. And I live at 626 East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi…

John Biewen: The Freedom Democrats chose Fanny Lou Hamer as their most important witness before the Credentials Committee. She spoke for eight minutes without notes, her hands clasped in front of her. Mrs. Hamer told the story of her beating in the Winona jail the previous year. Her crime, again: using the whites-only restroom at a bus station.

Fanny Lou Hamer: And it wasn’t too long before three white men came to my cell. One of these men was a state highway patrolman. And he said we’re going to make you wish you was dead.

John Biewen: The jailers put her in a cell where two Black men were locked up. The authorities ordered the Black men to beat Mrs. Hamer with a Blackjack, a police baton.

Fanny Lou Hamer: After the first negro had beat until he was exhausted, the state highway patrolman ordered the second negro to take the Blackjack. I began to scream and one white man got up and began to beat me in the head and tell me to hush. One white man – my dress had worked up high. He walked over and pulled my dress, I pulled my dress down and he pulled my dress back up. I was in jail when Medgar Evers was murdered. All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings in America. Thank you. (Applause)

John Lewis: She stated the case. And she told her story and told the story of the people of Mississippi. And we really thought we had won the day.

John Biewen: Several Mississippians said they believed that if the credentials committee had taken a vote right then, they would have seated the Freedom Democrats and sent the all-white Democrats home. But party leaders intervened. Lyndon Johnson was afraid he’d lose any support he had among white southerners in the November general election, if the Freedom Democrats, the MFDP, were seated. Johnson asked Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey, his choice for vice president, to negotiate with the Freedom Democrats. Bob Moses.

Bob Moses: Johnson is the president and Johnson says, ‘If you wanna be vice president, then you deliver this.’ So it’s straight power politics.

John Biewen: Deliver this, meaning…

Bob Moses: The MFDP. You get this monkey off our back.

John Biewen: Humphrey’s young protege from Minnesota, and another future vice president, is Walter Mondale. At Humphrey’s direction, Mondale offers the Freedom Democrats a compromise. Two members of their delegation, one Black and one white, would be seated as delegates at-large. Members of the all-white party would be seated only if they promised to support Johnson for President. And the national party promised never again to seat a segregated delegation. Mondale announced the proposed compromise at the convention.

Walter Mondale: It may not satisfy everybody, the extremes on the right or the extremes on the left. But we think it is a just compromise.

John Biewen: Everybody rejected the plan. Most members of the all-white Mississippi party were Goldwater supporters. After Mondale’s proposal all but four of them left the convention. The Freedom Democrats said no to the compromise, too. Unita Blackwell, the organizer we heard from earlier, from Mayersville, was one of the party’s delegates.

Unita Blackwell: The compromise was two seats. And Miss Hamer said, ’Well, you know. We ain’t gonna take no two seats. All of us sixty-eight can’t set in no two seats.’

Walter Mondale: I would say first of all, they came with a powerful moral case….

John Biewen: I interviewed Walter Mondale in 1994.

Walter Mondale: Recounting the indisputable fact that Blacks in Mississippi were sealed out of the Democratic party, that the delegation that had been officially sent from Mississippi, which was all white, was selected on a rigged, discriminatory basis, and that our party finally had to do something about what was, uh, a moral disgrace.

Frank Smith: In the end, they just didn’t have the guts to do it.

John Biewen: SNCC staff member Frank Smith.

Frank Smith: Everybody agreed with us, they all knew it was wrong, they all knew it violated the constitution, they all knew it had to be done sooner or later, they all knew all of the right things. They just couldn’t do it at the time. And it disillusioned us a great deal. I think it disillusioned, actually, the civil rights movement quite considerably.

John Lewis: And I think that was a great disappointment.

John Biewen: John Lewis.

John Lewis: This could have been, I think, the real final straw, that set in a period of discontent and a period of bitterness, and a period of deep, deep despair on the part of a lot of young people who had worked so hard.

[Music]

John Biewen: Right after Freedom Summer, the young organizers felt they had taken on American racism and gotten trampled. They’d registered few Black voters in Mississippi. Their challenge to the Democratic Party had been turned aside. Dave Dennis was the Mississippi Director of the Congress of Racial Equality,

Dave Dennis: What it achieved more than anything else, I think, it exposed the system, from top to bottom. And what it did was to show that there was a conspiracy to some extent, unwritten — there was just so far that people were gonna go to make changes. They weren’t gonna step on too many people’s toes at this time in this country. And really what type of a rock this country was built upon.

John Biewen: Others, looking back later, had a more positive take on the summer and what it accomplished.

Lawrence Guyot: I think that every time we got someone to register to vote, to attempt register to vote, whether they were successful or not, every time we got someone white allowed to stay in their home, every time we got someone to stand up and say, ‘yes i’m going to the mass meeting,’ we had changed them. You don’t do that and then undo it two weeks later and go back to what you were before that act.

Robbie Osman: People came out of the Mississippi summer project and looked at the questions that affected our lives ever after — questions about gender, questions about sexuality, questions about war and peace, and we had real knowledge of a way to function.

John Lewis: What we were unable to do, maybe, in Mississippi, but we were able to build on Mississippi, build on Atlantic City, and I think we did it in Selma.

John Biewen: The Selma to Montgomery March, in the spring of 1965, was followed a few months later by the signing of a landmark bill. John Lewis: The Mississippi summer project laid the foundation, created the climate, for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, to make it possible for hundreds and thousands and millions of Blacks to become registered voters.

[Music]

John Biewen: Hey Chenjerai.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Hey John.

John Biewen: This seems like another one of those stories where, when you add up the outcomes, there’s good news and bad news, and you have to decide which to tell first but also, which is more important, which to emphasize.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Yes. Cause you know, we always want to try to take the right lessons from this history. And I think that it’s tricky because there was a defeat. We can see that despite all of that organizing by the Mississippi Freedom Democrats, Johnson and them felt like they were facing this dilemma and, I mean, the thing is, they knew that the Mississippi Freedom Democrats’ proposal was to seat the delegation that actually represented the state. That’s clearly the more democratic option.

John Biewen: Yes. And that had actually followed the party’s own rules for how you choose a delegation. Unlike the other one.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Exactly. And yet ultimately they come out in a way that can only be described as against democracy, really, in that moment. And so I think, you have this example right of the Democrats claiming to represent the most vulnerable members of the party, but then it kinda feels like they sold those members out. Then the excuse they give is that they have to appease this conservative faction within the party.

John Biewen: And this is a very real thing for people, right? People really think they’re making a hard-headed political calculation — we may have to give up our deepest principles right now but at least that’s gonna help us win and hold onto power so we can do more good down the road. But how did that work out in 1964?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: See, that’s the key question. What you have to pay attention to is that the southern states that you worked so hard to appease? What did they do. Well Mississippi and 3 other states ultimately voted for the republican president, Goldwater, who was just coming out with this explicitly racist platform. They sorta felt insulted that they were asked to be more democratic.

John Biewen: So Lyndon Johnson didn’t get those electoral college votes anyway. After bending over backwards to please the white southerners at the convention. But mostly here we’re sort of focusing so far on the bad news side of the story.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right, yeah. I mean. All of that is true, but I still think that that’s a short-sighted way of understanding the legacy of Freedom Summer. So there’s a longer and wider story about that, that has to be told. And one place that you might start is, like, in the process of that really contentious Convention, the DNC offers the Mississippi Freedom Democrats this compromise. They said we’ll seat two of your delegates without voting rights and all this other stuff. And then maybe next time, or something. And you know, the Mississippi Freedom Democrats reject that. You can just see Fannie Lou Hamer like “I didn’t come all the way up here for this.” But that compromise that the DNC offered sets a precedent that over time transforms the delegation process and ultimately transforms the Democratic party itself. It winds up becoming kinda institutionalized in ’72 when they create like this McGovern-Fraser commission to figure out, to look at contentious moments like that. And once that stuff is institutionalized, it paves the way for this, like, unprecedented increase of Black elected officials at the local level, some at the national level, judges, etcetera. And their policies really do make a difference in a number of ways.

John Biewen: Yeah. So, it’s really, it’s a really powerful legacy of the Mississippi Freedom Democrats. And speaking of the longer view, there’s an aspect of the Mississippi Summer Project, Freedom Summer, that we really haven’t even mentioned up to now. And you and I agreed we have to at least touch on it here, and that is the Freedom Schools.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s it. You know, I mean, again, this is one of the limited ways that I think sometimes people only look at the success of things in terms of specific electoral victories or something. But social movements are also these places where people are learning new strategies, new ways to organize, and the Freedom Summer was a really incredible example of that. So you had this, while they were doing the voter registration and building the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, some Black civil rights workers and white student volunteers actually spent the summer running these schools all over Mississippi. They invite Black children to spend their day at those schools, they’re teaching Black history, including African history. They’re talking to them about the political and economic realities of Jim Crow. And the goal was to plant seeds in the minds of those young people, who were definitely not supposed to think for themselves according to the racist power structure.

John Biewen: Yeah exactly. The education system was not only profoundly – actually the white schools got four times the funding that the Black schools got, and even the white schools were poorly funded, so imagine. And then also, the schools, Mississippi schools at the time did not teach foreign languages, and they didn’t even teach civics.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: Yeah, I mean it’s just, you see scholars and people who lived through that and they say, you know, this was a system explicitly designed to stifle independent thought and self determination. I mean how do you not teach somebody civics, right?

John Biewen: So the Freedom Schools were part of a long-term strategy built in to Freedom Summer to really build democracy by creating politically aware young Black citizens who would understand that they had to get involved and stay involved if their world was gonna change. It’s really, just interesting and brilliant grassroots movement building strategy.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. And all those things, like protests, and that deeper organizing, inspires student struggles beyond the southern movement. You see it in groups like the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Student Movement (NSM), etc. And then some of those movements, right, they’re also taking it past simply electoral politics, I mean, even looking at the school and other places, as sites for expanding democracy. But I do think it’s important that in the wake of what would seem like a, I mean what was, a devastating electoral defeat at the Convention, the SNCC leaders still don’t cede the territory of the vote. That’s really important. They don’t give up on electoral politics because they understand it’s too important. And that effort that starts in Jackson actually continues years later in other places, right? One of the most important places is the Lowndes County, Alabama organizing. Kwame Ture (formerly named Stokely Carmichael) and other leaders went down to Lowndes and formed something called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. The Lowndes County organization is also the origins of the Black Panther symbol, because they choose that symbol.

John Biewen: Yeah, and I had learned that in the process of doing this Freedom Summer thing, but one thing I didn’t know until you told me just recently: the Democratic party, the all-white Democratic party in Alabama at the time, its symbol was a white rooster.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: yeah, so Alabama Democrats have a white rooster and a slogan that says, and I quote, “White Supremacy – for the right.”

John Biewen: So white supremacy is in the slogan of the Democratic party in the 1960’s in Alabama.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. And they kinda get rid of the slogan but they keep the symbol, which kind of evokes that slogan, all the way up until 1996. And so this choosing of the Black panther symbol was in part a response to that because, you know, they had this saying, where they were like okay, you got a rooster, but Black panthers eat roosters.

John Biewen: I’d put my money on the Black panther every time against a rooster. So that was the origin of the Black panther being adopted as a symbol, and then it was adopted by the much more famous Black Panthers of Oakland, California.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: That’s right. They became aware of that symbol, and you know, the other part of the message which was that what happens when a panther is backed into a corner and they have to fight, right. So Huey and Bobby Seale adopt that symbol, but they also later recruit Stokely Carmichael as honorary prime minister of the party. So yeah, but going back to the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, it wasn’t just that they had this symbol, they did some concrete organizing. In 1966 they registered over 2000 people, and then five years later they elected their own activists as Mayor, County Commissioner, and Sheriff, right? That’s not necessarily the end of the revolution or something, but it did have concrete effects on Black life in that area. And when I look at local politics, I mean here in Philly we have city council members like Helen Gym, Kendra Brooks who was recently elected, Larry Krasner, our DA—I mean whether we’re talking about sanctuary cities, the coronavirus relief, that ability to control politics at the local level has been really important for vulnerable groups to push back when the national party feels that their demands are too radical.

John Biewen: And I think this is important, this point you’re making. Because I think a lot of people look at, we look mostly at politics at the national level, and we think that what matters are the leaders themselves, who are we gonna vote for, the actions they’re taking, and people out in the world maybe engaging in activism at the local level but that’s mostly about local issues and doesn’t really have much to do with what’s happening nationally. That’s kind of a separate thing. And I think that what can get lost in those narratives is the way that local activism really can make stuff happen at the national level too. And this is a really a powerful example. Another thing we haven’t mentioned yet is that it was during the summer of ’64, in July of that year, that congress passed and Lyndon johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. Huge, landmark legislation, along with the Voting Rights Act of ’65, the other major piece of legislation of that period that really dramatically pushed Civil Rights ahead in this country. Remember the Civil Rights Act banned segregation in public institutions, and it outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, or national origin.

Chenjerai Kumanyika: And that law was passed because of activism by Black folks in places like Birmingham, in Alabama. People forget that Kennedy was dragging his feet on Civil Rights during the first couple years in office. People like Martin Luther King weren’t too sure about Kennedy, actually. But the movement and the violent white response to it finally forced him to act. And then after Kennedy is assassinated, Congress passes the law, and Johnson signs it. So, it’s not some biased, partisan argument, right? It’s the verdict of history that that is what works. Sustained activism over time, relentless pressure by people’s movements on the ground.

John Biewen: The other thing that it seems like we keep learning though, Chenjerai, is that victories like these, victories that advance democracy and equality, they’re never won permanently, are they?

Chenjerai Kumanyika: No. it’s a history of struggle. And you have to fight to maintain those rights. Because there’s always forces trying to take them away.

[Music]

Laura Free: Hi again, it’s Laura Free. Thanks for listening to this special bonus episode of Amended, from Scene on Radio, courtesy of the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. You can hear Scene on Radio anywhere you get your podcasts, or at sceneonradio.org. The episode you just heard is a great reminder that when we talk about social movements, no victory is ever complete. Following the passage of the Voting Rights Act, activists kept pushing to make that legislation work for them, and to make American democracy live up to its ideals of equality and justice for all. That work continues today.

[Music]

Laura Free: In 2013 the Supreme Court decided that the Southern states no longer needed federal approval to change their voting laws, and that ushered in the modern era of voter suppression tactics. Things like closing polling places in areas where people of color live, or restricting the availability of drop boxes for collecting mail-in ballots. Today voting rights activists are pushing for the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. It aims to restore the protections of the original Voting Rights Act.

Laura Free: Next time on Amended, we’ll go back in time again, to look at the tactics that were designed specifically to exclude Native Americans from citizenship and voting and tell the story of a Yankton Dakota suffragist who set out to change that. Please listen through to the end so you can hear about the incredible people who make Scene on Radio.

[Music]

John Biewen: The show’s website, where we post transcripts and other goodies, is sceneonradio.org. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, @sceneonradio. Chenjerai is @catchatweetdown. Our editor this season is Loretta Williams. Music consulting and production help by Joe Augustine of Narrative Music. Our theme song, “The Underside of Power,” is by Algiers. Other music this season by John Erik Kaada, Eric Neveux, and Lucas Biewen. The freedom song recordings in this episode were courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways. Archival audio from the 54 Mississippi Department of Archives and History. This episode was adapted from the 1994 documentary Oh Freedom Over Me, produced by me with consulting producer Kate Cavett. It was a Minnesota Public Radio production from American Public Media. Big thanks to Michael Betts II for production help in making this adaptation. Scene on Radio is distributed by PRX. The show comes to you from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

“Freedom Summer” Credits:

Produced by John Biewen, with series collaborator Chenjerai Kumanyika. Interviews with John Lewis, Bob Moses, Unita Blackwell, Hollis Watkins, Dorie Ladner, and many others. The series editor is Loretta Williams. Freedom song recordings courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways. Other music by Algiers, John Erik Kaada, Eric Neveux, and Lucas Biewen. Music consulting and production help from Joe Augustine of Narrative Music. This episode was adapted from the 1994 documentary Oh Freedom Over Me, produced by John Biewen with consulting producer Kate Cavett. It was a Minnesota Public Radio production from American Public Media. Scene on Radio is a project of the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

Original air date: April 1, 2020

The Amended Team:

Production Company: Humanities New York

Laura Free, Host & Writer

Reva Goldberg, Producer, Editor & Co-Writer

Scarlett Rebman, Project Director

Vanessa Manko

Sara Ogger

Michael Washburn

Art by Simonair Yoho

For this bonus episode of Amended:

Music: Live Footage and Pictures of The Floating World

Amended is produced with major funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and with support from Baird Foundation, Susan Strauss, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Phil Lewis & Catherine Porter, and C. Evan Stewart.