The scope of women’s political history is so vast that it can’t be covered by one podcast. This week Amended host Laura Free introduces a special episode from And Nothing Less, a seven-part series from the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission and PRX. This episode is more than a story about women’s rights. It’s a story about civil rights. And women like Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell understood that the suffrage fight was as much about race as it was gender. Hosts Rosario Dawson and Retta speak with some great guests you’ll recognize from Amended—like Martha Jones and Lisa Tetrault—and some you haven’t met yet—like Michelle Duster, great-great granddaughter of Ida B. Wells, and historians Alison Parker and Marjorie Spruill.

Laura Free: When leading white suffragists spoke out against the Fifteenth Amendment in the 1860’s—arguing that white women should get the right to vote before Black men—their complaint was steeped in racial privilege and prejudice. Last time on Amended, we learned how Black poet, speaker, and activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper stood up to call these women out, and that she was not the only one to do so.

Sharia: You white women speak here of rights, I speak of wrongs.

Laura: She was also not alone in her pursuit of a more inclusive vision for women’s rights that left no one behind. Each episode, groundbreaking historians are bringing us the stories of women who fought for the rights of their sex and against oppression based on race, citizenship status and class.

Martha: There have always been black suffragists as long as there have been suffragists.

Judy: We don’t want to write people out who were actually there.

[Music]

Laura: You’re listening to Amended, a podcast from Humanities New York. I’m Laura Free. We’re working on some more stories for you: Episode 4 is about different women immigrants living and working in New York City in the 19-teens. Episode 5 is about indigenous women activists who worked to gain political power in the 1920’s, without losing national sovereignty. And finally, Episode 6 will feature some contemporary activists who are pushing to make voting accessible for all today.

The scope of women’s political history is so vast that it can’t be covered in one podcast. That’s why we’re really excited to bring you a few episodes from our other favorite shows: shows about suffrage specifically and about civic participation more generally, shows that talk about the past, the present, and how they tie together.

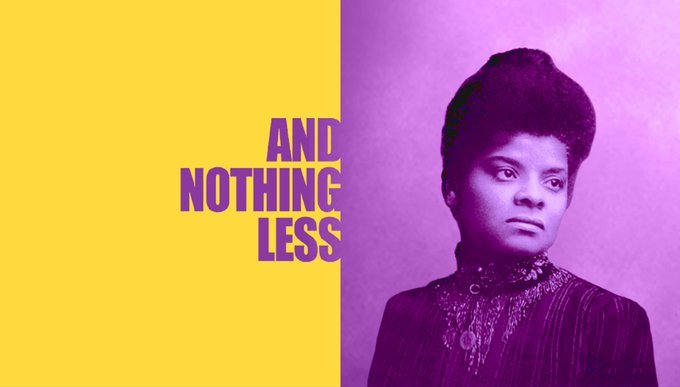

And Nothing Less is a great podcast from the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission, the National Park Service, and PRX. This show shares our commitment to challenging what many of us think we know about women’s right to vote. The show is hosted by Rosario Dawson and Retta, and they share important suffrage stories that have been left out of the textbooks, and introduce us to under-recognized heroes who deserve to be household names. And Nothing Less also brings you the voices of some incredible historians—some you’ve heard on Amended and many you haven’t.

The episode you’re about to hear is called “Truth Is of No Color.” In it, you’ll hear about Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, leading Black women activists who——like Frances Harper——never saw women’s suffrage as separate from the struggle for civil rights. We’ll hear what they did to organize and mobilize to transform the nation’s political landscape.

Now I’ll turn it over to Retta and Rosario. Enjoy this episode from And Nothing Less!

[Chicago ambience]

Retta: A couple of years ago, if you were driving in downtown Chicago from the expressway toward Lake Michigan or walking down the road past the Auditorium Theater, you’d be on a street called Congress Parkway. And you wouldn’t have thought much of it. But now when you turn onto Ida B. Wells Drive, you notice a new name on the block. And wonder how she got here.

Michelle Duster: It’s the first street name change in the city of Chicago in over 60 years. And it’s the first street name in Chicago, in downtown Chicago after any woman or any person of color. And so for Wells to be both African-American and female, I guess she’s a two-fer.

Retta: Standing on Ida B. Wells Drive, in front of the Harold Washington Library, which was named after the city’s first black mayor, is Michelle Duster. She’s Wells’ great-granddaughter and a public speaker and educator. And she worked with the League of Women Voters and the city to get her great-grandmother’s name recognized. When Ida B. Wells moved to Chicago at the age of 32, she was already an established activist in the fight for civil rights and anti-lynching, as well as an investigative journalist. And of course, she also wanted to empower women. And that meant giving them a voice. And a vote. In 1913, Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, which was the first suffrage organization for black women in Chicago. This emphasis on the importance of voting and her great-grandmother’s legacy was constantly with Duster when she was growing up.

Duster: I grew up hearing never ending, you know, people, white folk who fought for this right. People died for you to have this right. And so I think there was always that emphasis on, like, let your voice be heard and make sure that you participate in your own civic engagement.

Retta: Wells was not alone. African American women suffragists were fighting for justice all over the country, and had been for decades. And their stories tell us they had as much — and sometimes more — at stake in the struggle, as white women.

Martha Jones: African-American women are no different than any community of Americans in that they see access to the ballot as a way to participate in the body politic and to enjoy power and influence around law and policy in the United States. That’s a shared story.

Retta: That’s Martha Jones. She’s a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and the author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote and Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.

Martha: African-American women by the 1820s are beginning to ask pointed questions about their relationship to the body politic, their relationship to power. They are leveling by the 1820s a critique of racism and sexism. Simultaneously, they are holding a high bar for the nation as a whole when they decry both racism and sexism.

Retta: And now in this centennial year, as we look back on suffrage history, We think there’s a pretty high bar when it comes to being honest about the role of race and racism. This is more than a story about women. This is a story about civil rights.

This is And Nothing Less, Episode 3. “Truth is of No Color”

[Theme Music]

Martha: The way black women distinguish themselves is that their story doesn’t begin in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York. Black women don’t participate in the Seneca Falls meeting, but they’ve already been for decades at work on their own fight for political power.

Rosario Dawson: Speaking to us again is historian Martha Jones. The story, as she puts it, began well before 1848, not in traditional suffrage associations, but in anti-slavery societies, churches and political party conventions.

Martha: And that campaign will not end in 1920. African-American women must continue the struggle for voting rights after ratification of the 19th Amendment, because, of course, Jim Crow laws are going to continue to disenfranchise so many black Americans, men and women

Rosario: That’s why, when we talk about rights for women, we also have to talk about slavery.

[Music]

Virtually all of the early suffragists were abolitionists. Though not all abolitionists were suffragists. Before the Civil War, white and Black suffragists and antislavery organizers worked together toward a common cause. Formerly enslaved people and free Black women like Harriet Tubman, Maria Stewart and Sojourner Truth were active in women’s rights circles.

Retta: Another famous abolitionist and formerly enslaved person who frequently spoke at women’s rights conventions was Frederick Douglass. In fact, he spoke at Seneca Falls, living just a horse ride away in Rochester, New York. And while living there, he established his abolitionist paper “The North Star” in 1847. But he used it to do more than just denounce slavery. He also talked about equal rights for women and other oppressed minorities. In fact, the paper’s masthead inspired today’s episode title “Truth is of No Color.” The full line read: “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

[Music]

Rosario: So before and during the Civil War, there was a lot to unite the circles of Americans seeking equal rights under the law. But by the end of the Civil War in 1865, nearly 20 years after Seneca Falls, new freedoms and new questions about who should have what rights, sparked new debates. The Fifteenth Amendment, proposed in 1869 by Republican lawmakers to make sure the right to vote could not be denied on account of race, was extended to men and only men. And Suffragists had to choose between a win for some or a win for all.

Lisa Tetrault: Congress decides to endorse black male voting, but not female voting.

Rosario: Lisa Tetrault is a history professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

Lisa: And they propose Congress does the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, one of the last and final reconstruction amendments. And in that, they say that the states may not discriminate in voting on the basis of race, but they don’t say on the basis of sex.

Rosario: Suffragists find themselves split over the Fifteenth Amendment, and ultimately over race. If you remember Susan B. Anthony said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ask for the ballot for the Negro and not for the woman.” She and Stanton faced a hard choice, and decided to sever ties with the American Equal Rights Association and form the National Woman Suffrage Association.

Lisa: I mean, it’s a very ugly chapter. And it reminds us that just because you support the advancement of democracy for one group does not mean you support the advancement of democracy for all. And what will happen over the course of the suffrage movement’s career, the kind of conventional movement that we think of as they continually sacrifice folks of color for the advancement of white voting rights.

Rosario: But Lisa Tetrault reminds us —

Lisa: There were lots of suffragists who supported the 15th Amendment. And we have to remember that the problem is we narrowed this story from the vantage point of Stanton and Anthony and that also deeply skews our sense of the movement.

Rosario: In addition to Anthony’s National association, there was Lucy Stone’s American Woman Suffrage Association who supported the 15th. And these are just the white organizations. Black women and men are organizing in their own communities in support of the amendment. And according to Martha Jones, for many African American women, the 15th amendment victory is their victory. Even if the vote is not theirs.

Martha: African-American women are as involved in defending and realizing the complete potential of the 15th Amendment as they are in realizing what becomes a 19th amendment. That is to say, they understand that the Constitution needs to speak powerfully both to the problem of racism and sexism. If they ever expect to enjoy voting rights.

Alison Parker: I think one of the things that we should recognize is that black men and women always had us knowledge and a sense of their own rights as citizens and asserted them as fully as they could.

Rosario: Alison Parker is a professor of history at the University of Delaware.

Alison: After black men won the right to vote the black women participated in what were called colored conventions, where blacks got together to talk about their priorities for the kinds of legislation that they thought were most necessary, were the kinds of political movements that would mean the most to them. And so even though they did not have the right to vote, black women were part of those colored conventions. And I think that’s an important thing to recognize. The other thing is, is that they participated in thinking about and debating over’s questions about suffrage and about the role of the political parties.

Rosario: This understanding — that political power can’t just be based on gender, And it can’t just be based on race. It can’t just be fought for in the courts. Or in the streets. It’s all encompassing. This is exactly what Ida B. Wells understood. We’ll talk more about her and her fellow activist Mary Church Terrell in a moment on And Nothing Less

[MUSIC]

Retta: So just to remind you, up until the late 1800s, there were two rival women’s suffrage organizations – the National Woman Suffrage Association led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone, among others. And mostly their division was over strategy. Stanton and Anthony were committed to a federal amendment. And Lucy Stone’s camp wanted to take a state-by-state approach. But the other sticking point was race. And those divisions were ugly. But in 1890 they decided the only way they could achieve their ultimate goal, which was a vote for women, was to unite. And so you had one group – the National American Woman Suffrage Association, simply known as “the National.”

But, while united, it was still largely only a white organization. So in black communities, women were organizing and forming clubs of their own. Ones that would build powerful connections and influence.

Martha: African-American women have by the early 20th century been working for half a century through the club model that is local organization and a national network.

Retta: You remember historian Martha Jones

Martha: And it has proven effective, powerful, and it has built this really robust community of black women activists. It is for African-American women essential to a political vision that always is remaining rooted in the material circumstances of black women, their families and their communities. And the club model permits that kind of intelligence, that kind of insight to always be a part of club deliberations.

Retta: And Ida B. Wells is perhaps the embodiment of a club leader.

Martha: Ida Wells is the quintessential example of an African-American woman activist in the late 19th and early 20th century. Wells is such an ideal example, because her politics are never one note.

Retta: It’s why we chose her image for our podcast! She totally embodies the notion of “And Nothing Less.” And many people who admire Ida B. Wells…who walk or drive down Ida B. Wells drive, think of her as primarily an influential anti-lynching activist. Or an ahead-of her time journalist. This formerly enslaved woman, born in Mississippi, was also there for the founding of the NAACP. And yet, people might not talk about her role in securing the vote.

Martha: Even before 1920, Wells helps us appreciate how the term suffragists just doesn’t do justice to black women activists who are like Wells, anti-lynching advocates, civil rights advocates, club women and voting rights advocates all at the same time. And this is the model. This is quite typical of the women of Wells’s generation and beyond who are nimble and versatile in their political vision and in their political activism.

Retta: Suffragists like Wells, were nimble, as we hear, because, like their white partners, black women linked the right to vote with a host of other issues. Suffrage meant education. It meant fair labor. It meant access to the press. And of course, it meant political power — to pass laws against lynching and to break the corrupt machines that were destroying black communities.

[MUSIC]

For black people, suffrage also meant racial justice. And while fighting for these rights, black suffragists would have to deal with discrimination within their own ranks.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, particularly in the South, the mainstream suffrage movement not only accepted discrimination, but encouraged it.

Marjorie Spruill: There was this massive effort on the part of powerful politicians to reassert white supremacy over Southern politics, and they had been driving black men from the polls through violence.

Retta: Marjorie Spruill is a professor emeritus at the University of South Carolina.

Marjorie: They had sometimes sort of coerced them or somehow persuaded them to vote certain ways, in other words, control their votes.

Rosario: It was within this environment that another leader in the black community also emerges – Mary Church Terrell. Like Ida B. Wells, Terrell was born in slavery. Her family was from Memphis. And the two actually knew each other as girls. Like Wells, by the time Terrell was a young woman, she had a strong belief in a woman’s right to vote.

Alison Parker: And this sense of her right to vote was an important step for her, because when she finally moved to Washington, D.C. and was living there, she was inspired to go and attend the National American Woman Suffrage Organization.

Rosario: Allison Parker is the author of an upcoming biography on Mary Church Terrell called Unceasing Militant.

Alison: And she went to one of their meetings and asked them if they would put on their agenda and create a resolution asking them to fight for black women’s rights and for the protection of all African-Americans. And Susan B, Anthony said, are you a member of this organization? She said, no, I’m not. But I hope that you would see that our causes are linked. And this was a really interesting moment because Susan B Anthony invited her to the podium and allowed her to put a resolution in favor of black rights and civil rights protections into the agenda of that meeting. And they became friends after that point and worked together on several occasions.

Rosario: Parker explains that Terrell’s relationship with Susan B. Anthony represents this balancing act that many African American women activists had to achieve at the time.

Alison: And Susan B Anthony also invited Mary Church Terrell, along with several other black women, including Ida B Wells, to stay at her home when she would invite them to Rochester to give speeches, even though she also participated in a lot of racist rhetoric and strategic decisions that excluded black women from considerations about the vote, she was a complicated person and was more likely to participate in acts of social equality than most white women at the time. And so this is something that made Mary Church Terrell, always willing to consider her and other white women and women’s white women’s organizations as groups that she should work with, even as she saw their flaws and saw which black women were being excluded or insulted. She never pulled away entirely from them. She decided to become the head of the first black women’s organization that was designed to promote civil rights and black women’s rights. But she didn’t ever want to be working entirely in an all black environment because she believed that as part of a minority, she had to do what she could to try to get buy in from white women.

Rosario: The anti-black racism that had always run through the suffrage movement was on display at one of the most critical points on the road to the 19th amendment. And both Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell were there for it. This was the 1913 women’s parade in Washington D.C.

[MUSIC]

Organized by Alice Paul, the founder of the National Woman’s Party, it was scheduled for the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. This is a celebration of a new president. And the first President from the south since Reconstruction. And the parade would reflect that. The black suffragists were asked to march in the rear.

Alison: And if you look at a movie like HBO’s Iron Jawed Angels, for example, you’ll see that there is one incident of a black woman who tries to participate in the parade. And that black woman is Ida B Wells. And the way that the story goes is that she has a confrontation with the parade organizer, the Quaker suffragist, Alice Paul, and she decides to disobey the segregation order and go on ahead and insert herself in her Illinois delegation.

Rosario: Parker says this story is true. But the way it’s been told, you might think Wells was the only black woman who refused to be segregated. The truth, she says, is much more interesting.

[MUSIC]

Alison: Alice Paul did indeed try to keep black women out of the parade because she wanted to court white Southern women and was interested in making it a national movement, but did not think of black southern women’s support as being included in that. So instead, what happened is that African-American women who asked her if they could participate got a no and then eventually got a “Well, you can do it as long as you stay in the back.” But they decided to organize, to protest. So they sent many petitions and telegrams to the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and basically said, she can’t do this. You can’t have a parade where African-American women are segregated like that. And there was so much of a backlash that even up to the day of the parade, there were debates about this. And what happened was that on the day there were multiple places and sites of contestation where black women were asserting their right to be part of it.

Rosario: Mary Church Terrell was one of these women. She was enlisted to help marchers from the Delta Sigma Theta sorority from Howard University. That’s a historically black sorority. But they wanted to march with the groups of other college women. Not to be segregated in the back.

Alison: And then the National Association of Colored Women was invited to join the New York delegation. All of the states were from the beginning marching in the back because that’s what the processional chant meant. So technically speaking, Mary Church Terrell and the NACW marched at the back in the New York section, but it was certainly not in a segregated section, nor did they quote unquote, agree to march in the back. And there are lots and lots of articles that say in white and black newspapers that talk about these, the fact that the march was, in fact, integrated and that black women were found throughout. So my hope has been that with this suffrage anniversary, we can start to tell this more interesting and complicated story.

[MUSIC]

Retta: Complicated indeed. Especially when you think about the victory of 1920. By that summer, the suffragists had won thirty five of the thirty six states they needed in order to reach the necessary two-thirds majority required for a constitutional amendment. Looking at the political situation in the remaining states they were left with one option that made the best sense – Tennessee. So what did this mean for the black women in this fight? Tennessee, like other Southern states, was a place where Jim Crow laws were enacted to make it almost impossible for black men to vote — literacy tests, grandfather clauses, poll taxes and violence. What should be different for black women?

It wouldn’t be, explains Martha Jones.

Martha: White suffragists not only know that Jim Crow laws will keep black women from the polls, they count on that being common knowledge because it permits them to make the case for women’s suffrage in the southern states. The promise is that the 19th Amendment, in fact, will not change the political status of African American women and that makes the 19th Amendment palatable for those who oppose black voting rights generally and certainly those who oppose the prospect of black women voters after a constitutional amendment.

Retta: Take the poll tax, which required eligible voters to pay a fee before they could cast a ballot. In each state a law like that would initially be written to only include men. And the goal was to keep African-American men, as well as poor Americans and other people of color, from voting. With the 19th Amendment, state lawmakers would make sure poll taxes would include men AND women. And black women in the South knew this. After the19th Amendment was ratified, women of color in the South experienced racist policies that would keep them without full voting rights until decades later. Racist policies that the 19th amendment did nothing to prevent or correct. And 100 years later, Martha Jones can’t help but wonder “what if.”

[MUSIC]

Martha: Historians don’t like really to play with hypotheticals, but I’ll try this one. You know, what if suffragists in the 19 teens and 20s had held out. And insisted that the only women’s suffrage amendment that they would advocate for, that they would support, was one that promised all American women the vote or guaranteed women the vote without respect to race, color, previous condition of servitude. What if white and black women had linked arms and continued the campaign for women’s suffrage and helped to turn this nation in a way from white supremacy early in the 20th century? For me, that is a powerful “What if?”

[MUSIC]

Laura: Hi again, it’s Laura Free. host of amended. I want to tack on another “what if” to Martha’s. I really love the episode we just heard. because it’s about the strategic choices black suffragists like ida wells and mary terrell had to make as they navigated the racism of white suffragists. And it also illustrates that these moments of intersection between black and white activists are only a small part of the organizing black women did. not only for suffrage, but against racist laws, too.

So here’s my extra what if: what if we change how suffrage history traditionally gets taught, so that, like in this great episode of and nothing less, black women are positioned at the center of stories about women’s activism. what if we taught about the struggles against sexism and racism not as isolated problems that white women and black men worked on separately, and instead recognized that there were also powerful black women tackling oppression at its heart, through church communities, an extensive network of black women’s clubs, and, later, civil rights organizations. they were there all along, honing strategies and laying the groundwork for future generations of activists.

[music]

Thanks for listening to this special bonus episode, courtesy of PRX. you can hear the full season of “and nothing less” right now anywhere you get your podcasts. The national park service has listener companion guides for this episode, and there’s a link to it in our show notes. Please listen through to the end so you can hear about the incredible team behind And Nothing Less…

Additional Resources

Visit the National Park Service website for a Listener Companion to this episode of And Nothing Less, and be sure to listen to the rest of the seven-part series.

Learn more about the history of women’s suffrage on the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission website.

Explore the newly launched Black Women’s Suffrage collection from the Digital Public Library of America.

Learn more about Mary Church Terrell in this short animated biography from Unladylike2020, an HNY Grantee.

And Nothing Less Credits:

And Nothing Less was envisioned by WSCC Executive Director Anna Laymon, with support from Communications Director Kelsey Millay. Executive Producer: Genevieve Sponsler. Producer and Audio Engineer: Samantha Gattsek. Writer and Producer: Robin Linn. Original Music: Erica Huang. Additional Support: Ray Pang, Jocelyn Gonzales, Jason Saldanha, John Barth. Marketing Support: Ma’ayan Plaut, Dave Cotrone, Anissa Pierre. Booker: Amy Walsh. Logo: Stephanie Marsellos.

Original Airdate: August 19, 2020

The Amended Team:

Production Company: Humanities New York

Laura Free, Host & Writer

Reva Goldberg, Producer, Editor & Co-Writer

Scarlett Rebman, Project Director

Kordell K. Hammond

Nicholas MacDonald

Joseph Murphy

Sara Ogger

Antonio Pontón-Núñez

Michael Washburn

Audio Editor and Mixer (for Amended): Logan Romjue

Art by Simonair Yoho

Music (for Amended): Michael-John Hancock and Live Footage

Amended is produced with major funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and with support from Baird Foundation, Susan Strauss, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Phil Lewis & Catherine Porter, and C. Evan Stewart.

Copyright Humanities New York 2020