In 1912, Mabel Lee, a teenaged immigrant from China, led a New York City suffrage parade on horseback. Ineligible for U.S. citizenship due to anti-Chinese immigration policy, Mabel nonetheless spoke out for American women’s political equality. She envisioned a world where all women had the right to vote—and she wanted white suffragists to pay attention to the discrimination and racism faced by Chinese American women.

In this episode, producer Reva Goldberg travels to Chinatown to meet with Reverend Bayer Lee, who honors Mabel’s legacy as the pastor of the church community that Mabel and her parents dedicated themselves to building. Host Laura Free speaks with Dr. Cathleen Cahill, author of Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement, to learn about Mabel’s political goals for women and for China. In the end, it’s clear that Mabel Lee forged a bold life according to her values.

Narration: On the afternoon of May 4, 1912, about 10,000 woman suffrage activists began a march through New York City, from Greenwich Village up Fifth Avenue. It was the biggest public demonstration—for any cause—that the city had ever seen.

Bands played lively music as the marchers went by in rows, four-across. They carried signs, and waved pennants and hats in the air. The youngest were pushed in baby carriages. The oldest rode in cars. And about 1,000 pro-suffrage men walked in solidarity with the women and girls.

The New York Times called it quote: “a parade of contrasts. . .there were women of every occupation and profession, there were women who work with their heads and women who work with their hands and women who never work at all.”

The parade was just a year after the Triangle Fire we talked about last episode. And garment workers came out in force. A group of them carried signs to honor the lives lost, making sure no one forgot how deadly it was to lack a political voice. There was also a large delegation of Black suffragists who marched against sexism and racism in the American democracy. The white organizers had asked all marchers to wear white, but Black suffragists wore black, perhaps to signify resistance to the racial prejudice within the suffrage movement itself.

[Music Change]

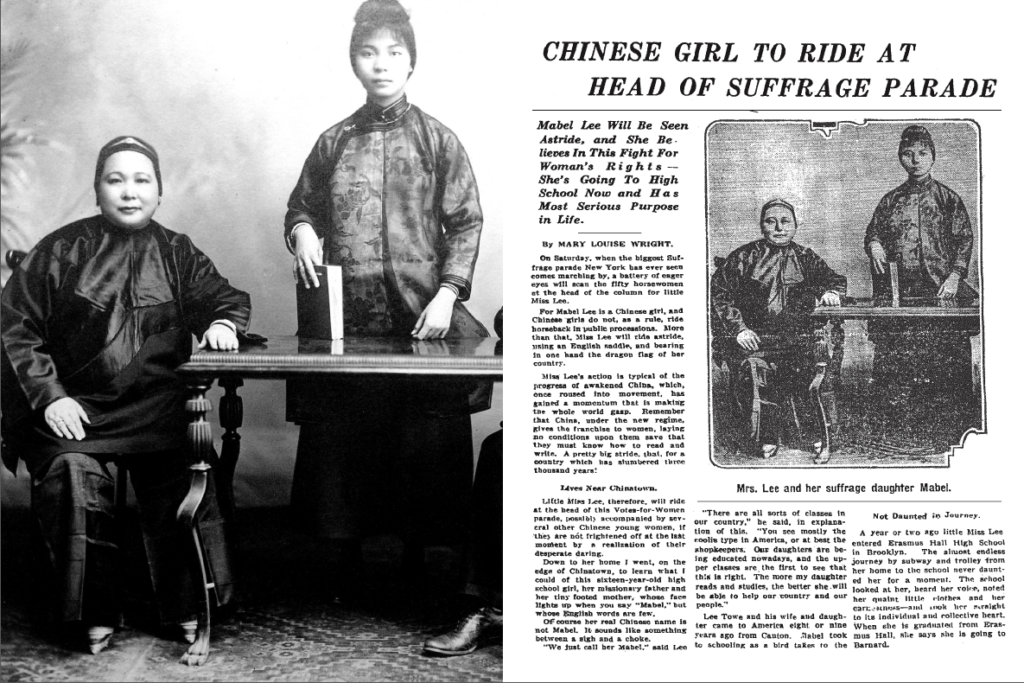

With hundreds of thousands of people watching, it must have been hard to see all the action if you weren’t in the front row. But there was one section that everyone got a good look at: 52 women and girls had been given a position of honor, leading the parade on horseback high above the crowd. As far as we know, all these riders were white except for one: Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a 16-year-old immigrant from China.

Anti-Chinese racism was everywhere in U.S. culture and policy. Chinese immigrants were barred from becoming citizens, let alone voters. And yet, here was Mabel, riding past the cheers and the hecklers, laying claim to her fundamental rights.

Our story today is about what led Mabel to this moment and beyond it. And more importantly, how she made a path for herself, when both of the countries she called home were resisting the call to expand women’s rights.

[Theme Music]

Narration: Welcome to Episode Five of Amended, a podcast from Humanities New York. I’m Laura Free. If you’re joining us for the first time, please start with Episode 1. Amended is meant to be heard in order. We’re traveling from the 1800’s to the present day, looking at the struggle for women’s voting rights through the stories of women who fought for full equality, and against discrimination based on race, citizenship status, and class. We’re talking about what’s been gained, what’s been lost, and what’s still left to be done.

[Theme Music Out]

Reva: Alright, so I’m going to give you a little countdown, and then, just tell me where we are and what we see around us.

Bayer Lee: Okay.

Narration: A few months ago, my producer Reva masked up and went to meet reverend Bayer Lee.

Bayer Lee: We’re in New York City, Chinatown. We’re standing on Pell St. One of the oldest streets in Chinatown. It also intersects with Doyers St., the most crooked street in New York City. Short and crooked.

Narration: Bayer came to New York from hong kong as a kid in the early 1960’s. His stepdad owned a laundry in Queens, and Bayer remembers him always saying he was going down to “the street,” That meant right here around Pell and Doyers, to meet up with friends who were also from southern China.

Bayer: On Sunday they’d dress up like Kings. With their suits, hats and long coats, and come down to the street. And they shopped, they’d catch up on the gossip, they’d go to restaurants.

Narration: Bayer’s stepdad and his friends weren’t the first to hang out here. The area had been a gathering place for southern Chinese immigrants for generations. Today, the streets are still lined with Chinese restaurants and businesses.

Bayer himself goes there to work. He’s the pastor of the First Chinese Baptist Church of Chinatown at 21 Pell St. It’s a three-story brick building with a front that looks like a pink and green pagoda.

Bayer: Would you like to come in?

[Sounds of footsteps, door opening and closing]

Narration: Bayer didn’t know it at first, but when he came here in 2004, his new job as pastor came with the role of lead researcher on the subject of Mabel Lee. Although they share the name Lee, Bayer isn’t a descendant of Mabel’s, but—for reasons we’ll explain later—the building that houses his church is also an archive of Mabel’s life, a life that was almost forgotten until Bayer showed up and noticed some old photos.

Bayer: I didn’t even know who she was, but up on the third floor, there were five photographs hung, huge black and white photographs. To my chagrin they’re turning yellow. One is the one by the window. Mabel Lee is standing in the middle, dressed in a traditional Chinese garb holding a book. To her right is her mother, also in a Chinese traditional garb. You can see her feet bound. Her father to her left was dressed in a Western suit, starched white collar. The organization of their picture is atypical Chinese. Well, usually the girl’s off to the side, right? So, very curious. Photographs at that time was highly organized and constructed with a message. So what was the message? I had no idea until recently.

[Music]

Narration: Starting with photos and documents he found at the church, Bayer has been piecing together the story of that family in the photo, and what they were communicating about themselves with the images and words they left behind.

The father in the meticulous western suit was named Lee Towe, and he was the first of the family to come to the U.S. He was just 12 in 1874 when he left southern China for the western United States. Starting in the mid 1850’s, thousands of Chinese men had come to the U.S. They were the majority of the workforce in two major industries: mining during the California gold rush, and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.

[Music Change]

But when the gold was gone, and the railroad was finished, unemployment surged in the West. White workers started to depict Chinese men as a threat to their jobs, and sometimes attacked or even murdered them. Towe arrived in San Francisco in the midst of these tensions. We don’t know what brought him to California, or how long he stayed, but we do know that his life changed course when he walked into a Baptist church in Oakland to learn English. Towe ended up converting to Christianity, and then going back to China to study theology at an American baptist seminary in Canton. That’s where he would end up meeting the seated woman in the photo, Mabel’s mother, Lai Beck.

[Music Change]

We don’t know Lai Beck’s birth date or what her early life was like, but given her bound feet, she probably spent much of her childhood confined to her parents’ house. Foot-binding was a Chinese practice passed down through women over centuries. Like the corset in Europe and America in the 19th century, foot-binding physically altered women’s bodies to meet an ideal vision of beauty and signal social status. By the time Lai Beck was in her teens, however, there was a growing movement in China to abolish foot binding, especially among Christians. At the same time, progressive Chinese activists and Christians were taking action to give more girls access to an education.

Lai Beck benefited from this movement. She was taught in her home by missionaries, and when she was old enough, Lai Beck went to the seminary in Canton to train to be a teacher. She met Towe there, and they got married. In 1896 they had Mabel.

[Music Change]

While the Lees had been studying and starting their family in China, anti-Chinese racism had become official policy in the U.S. In 1882, Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act to dramatically cut the number of Chinese immigrants allowed into the country, particularly manual workers. It also barred all Chinese immigrants from ever becoming citizens. Other groups of immigrants in the U.S. certainly did experience prejudice, but at the time, only Chinese immigrants were targeted with a law that called them permanent aliens.

All this hostility pushed many Chinese immigrants to settle together in large U.S. cities. They didn’t escape racism, but they were able to build communities, economies, and self-governing bodies in neighborhoods called “Chinatowns.”

The Lees felt called to serve these communities in America. And because Towe was a missionary and Lai Beck was a teacher, they were allowed to enter the U.S.

Mabel was 9 in 1905 when the American Baptist Association asked Towe to move to New York. He would be the minister at the Morningside Mission based on Doyers St. in Chinatown. Here’s Reverend Bayer Lee again:

Bayer: So he first started to evangelize, tried to give out Bible tracts, but not too many Chinese was interested. And so he began to go out to the community and wanted to find out the needs of the community. As a result, he got more and more involved in the issue, social issue, immigrant who needs to learn English. Immigrant who needs help in legal matters. So he got more and more involved with the physical, the social needs of the community.

Narration: Towe’s mission became a really important resource, and Lai Beck and Mabel threw themselves into serving the community, too. The Lees also dedicated themselves to giving Mabel every opportunity to become a modern Chinese woman. Just like in the family photo, she was the center of their lives.

The Lees did not bind Mabel’s feet, and they encouraged her sharp intellect. At home, she was immersed in Chinese history and literature. She learned to play the piano, and studied Christian theology. She also went to American public schools. First, a segregated Chinese school near home. Then the best high school in the city at the time—Erasmus High in Brooklyn. She was the only Chinese student in her class.

Bayer: And she was able to go because of the subway. So that took her out of Chinatown. And so part of her acculturation in the educational environment of the Erasmus high school and the faculty, many of them were strong women who advocated women being free, right? And educated.

[Music]

Narration: So Mabel’s parents had a progressive view of women, and her American teachers did, too. But there was another major influence on Mabel’s emerging feminist worlview. Back in China a decade of unrest had resulted in a revolution in 1911. The revolutionaries wanted to replace the emperor and install a democracy. And they promised to give women equal rights if they succeeded. There was an active woman suffrage movement in China at the time, and many Chinese suffragists joined the revolution. They believed it was their best chance to get a full voice in government.

So both the U.S. and China seemed to be on the verge of a reckoning regarding the status of women. As a girl with ties to both countries, Mabel must have been captivated by the possibilities.

She seemed to excel at everything she tried, and her future looked bright. The more gender barriers that women broke as she grew up, the more likely it would be that she could choose the life she wanted. Before she even finished high school, Mabel decided to help break those barriers. We’ll find out how, after a short break.

[Music Out / Sponsor Break / Music Up]

Narration: When Mabel was in high school, the number of Chinese women in New York was small. But she and her mother were part of a growing cohort of women who were making a major contribution to their community. Along with other wives and daughters of ministers and merchants, Lai Beck and Mabel were heavily involved with activist work. They did things like start kindergartens for Chinese children in the U.S. and send aid to the poor in China.

When the revolution for democracy in China began, this community of women became even more politically active. Mabel started giving speeches at meetings to talk about the change the revolution could bring. She was also part of a student group that hosted fundraisers for revolutionary leaders.

It was in the spring of 1912 when Mabel’s skills as a speaker attracted the attention of the American woman suffrage movement. I called Dr. Cathleen Cahill, a professor of history at Penn State University, to find out how.

Laura Free: Hey Cathleen, thanks so much for joining us.

Cathleen Cahill: Hey, thanks for having me.

Narration: Cathleen features Mabel’s story in her new book, Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement. She told me that in the early 19-teens white Americans were closely following news coverage of the revolution in China. they were especially intrigued by the role Chinese women were playing in it.

Cathleen: Women are involved in this revolution in some pretty visible and surprising ways. So there’s a women’s unit of soldiers that fight. Women are serving as spies and carrying bombs. And so Americans are reading about this, and they’re fascinated. ‘Cause the stereotype of Chinese women in the United States is that they’re all prostitutes or that they’re extremely subservient. So the idea of them fighting in a revolution just kind of blows Americans’ minds.

Narration: For some leaders of the American suffrage movement, these stories didn’t just challenge their prejudice. American suffragists started to wonder how the progress of women in China might benefit their own struggle for equality—especially after the Chinese revolution succeeded in early 1912, and a new government took control.

Cathleen: The news that comes back to the United States is that they have enfranchised women. It’s a little more complicated. They allow each province to decide if they will, and Canton, which is where actually most of the Chinese immigrants in the United States are from, has decided to enfranchise women. In a lot of cases it’s only educated women. So it’s not universal. But Americans are not parsing those specifics. They just hear China has enfranchised its women.

[Music]

Narration: White suffragists wanted to understand how Chinese women were making such progress, so in cities around the country, they reached out to Chinese women through church networks and asked them to meet and talk. One of these meetings happened in April 1912 at a high-end Chinese restaurant in midtown Manhattan. 16 year-old Mabel and her parents were there, along with other prominent women from their community.

The Chinese women were still celebrating the success of the revolution, but they came to the meeting to talk about something far more local: the anti-Chinese racism of everyday life in America.

Famous and powerful white suffragists, including Alva Belmont and Anna Howard Shaw, sat and listened as a Chinatown resident named Pearl Mark Loo told a disturbing personal story. Pearl was a teacher, and therefore exempt from the Chinese Exclusion Act. But when she tried to enter the U.S., she had been detained for months in a freezing San Francisco warehouse before finally being released. Mabel also gave a speech, and we have a short excerpt of what she said from a reporter who covered the meeting. Mabel said, quote, “All women are recognized in New York, excepting Chinese women. She is not included in your educational institutions. Your social and recreational centers do not include her. How can she learn!”

Cathleen: She’s apparently incredibly poised and charismatic as a speaker. Later, people will describe her as “Mabelizing” crowds, just holding them in awe with her speeches.

[Music]

Narration: Mabel’s speech at the restaurant was actually pretty gutsy. She directly confronted a group of prominent white women activists, and called them out for their privilege. Yes, they lacked voting rights, but they had so many advantages that were systematically denied to Chinese women and girls.

Because her father was a well-connected religious leader and her family was middle class, Mabel had opportunities to learn and thrive that many Chinese children lacked. Now she was using the platform she had to stand up to those with more power and to advocate for those with less.

The white suffragists came away impressed. They invited the Chinese activists to form a delegation in their upcoming parade, and they asked Mabel to ride at the front.

[Music Change]

So that’s how we arrived at that moment from the start of the episode: Mabel on horseback in front of hundreds of thousands of spectators. She must have been proud that she was selected as a leader, and that there was a whole delegation of Chinese women suffragists in the parade, too. The women, including her mother Lai Beck, carried the flag of the new Chinese republic, and signs that read “light from China.”

When I first heard this, it sounded like a great moment of intersectional alliance—where Chinese and white and Black and immigrant suffragists are all marching together for the same cause. But the parade was actually really segregated. The white women organizers grouped the participants by race, ethnic group, and class. And they didn’t stop there.

Marching directly behind the Chinese delegation was Anna Howard Shaw, the president of the largest suffrage organization in the country. Anna carried a sign that said “National American Woman Suffrage Association: catching up with China.”

In effect, Anna was saying that by holding women back, the so-called “progressive” U.S. was falling behind so-called “backwards” China. Anna had been at the restaurant meeting and heard all about the racism Chinese women faced, but she clearly cared less about what they needed, than she did about using them to promote her own message.

Cathleen: White suffragists are going to try whatever works to get attention to their cause. Because they’re very savvy about PR and they know that having a Chinese woman is going to bring attention to the parade. That’s going to get suffrage in the newspapers. It’s clickbait in our social media terms.

Narration: The Chinese marchers did get lots of press, and Mabel’s name and picture showed up in newspapers across the country under headlines like “Chinese Girl Wants Vote” and “Chinese Girl Suffragist.” The whole event was a rare moment of visibility for Chinese women in America, but it also remained to be seen if going forward they would be included in the white suffrage movement in a meaningful way, or if they would share in any gains women made in America.

[Music Change]

While Chinese suffragists in America wondered about their future, women in China were getting impatient to see the gains they had been promised during the revolution. American suffragists believed Chinese women were way ahead, but when it came to voting rights their status was actually pretty similar. Women had the vote in some regions of China, just like they did in some U.S. states, but both national governments still refused to fully enfranchise all women.

In both countries, suffragists were becoming more militant and daring. Some American suffragists started picketing the white house, getting arrested, and going on hunger strikes. And in China a group of suffragists tried to storm their new parliament, shattering the windows with rocks.

[Music Change]

As a young, ambitious person, just starting to make her path in the world, Mabel had to be on the edge of her seat. If the suffrage movements in either or both countries succeeded, it could mean a huge shift in what was possible for her future. We don’t know if Mabel had a specific career path in mind yet—I certainly didn’t at her age—but over the next few years she threw all she had into two things: academic excellence and women’s equality. It was like she was trying to be the living proof of what women could achieve when they were given the chance. And at the same time, trying to influence the future, so that there would be a place in it for high-achieving girls like her.

In 1913, Mabel entered Barnard, which was affiliated with Columbia, and was one of the most prestigious women’s colleges in the country. The essays and speeches she wrote there are a powerful record of the change she believed in. Here’s Cathleen again:

Cathleen: She sees the U.S. and British suffrage movements as fantastic. And she’s a big advocate of democracy and democratic institutions and sees the United States as a model for that. But she’s also critical and she says, look, both Britain and the United States built their democracies without including women’s rights. And she says U.S. and Britain are going back and kind of having to build it on. In China, we have the opportunity to build this new nation and to get women’s rights in there from the beginning.

Narration: If you’re sensing that Mabel’s message was more for a Chinese audience than an American one, you’re not wrong. She was one of only a few Chinese American women at Barnard, but Mabel belonged to an elite group of about a 1000 Chinese students who were in cities across the U.S., many of them were being groomed as future leaders for China, and Mabel was one of their rising stars. She was writing, speaking, and publishing ideas for an international community of Chinese scholars, business leaders, officials and diplomats.

And she was warning this audience not to make America’s mistakes when it came to women.

Bayer: Traditionally in China at that time, or even the world at that time, it’s that women is to be at home. You know, her calling is to be a good mom. Right? And she wrote about that limitation. About freeing the woman from bound feet, but more so in her emphasis is that education, learning. Calling for the women in China to have the same access to knowledge and professional vocation as the boys.

Narration: It was not just unfair to women as individuals to deprive them of education, opportunity, and suffrage, but it made women into what Mabel called the “submerged half” of the population. And that robbed the country of half its intellectual and economic power. It left, quote, “every other beam loose in the construction,” and that was an existential threat to the nation.

Mabel’s argument was a common sense one: “We all believe in the idea of democracy. woman suffrage,” she said “is the application of democracy to women.” Mabel also saw that American democracy wasn’t just failing women. She had seen it fail Chinese immigrants her whole young life. Anti-Chinese racism was part of the fabric of American culture.

Cathleen: She sees it in kind of cultural depictions of the Chinese that are in early film that are in dime novels. Chinatown tours that are advertised to the students at Barnard and Columbia. And it’s marketed as kind of like a ghost tour is now. Kind of a joke. Kind of scary. “Go to Chinatown and you’ll tour an opium den and you’ll see the dragons.”

Narration: These insulting, voyeuristic tours were in Mabel’s own neighborhood, and that wasn’t the end of it. On campus, Barnard students surrounded themselves with racist depictions of Chinese culture.

Cathleen: One of the years that Mabel is there, the mascot is the Chinese dragon. So it’s written up in the yearbook, right? and it’s described as this horrible serpent that the Chinese people worship. And you know, when I was reading that in the yearbook with Mabel’s picture in it, I was thinking, you know, what did this mean to her, right? Here’s this really awful stereotype of her nation being used as this sort of jovial part of college culture.

Narration: As harmful and alienating as it was for Mabel to see her culture misappropriated, Cathleen told me that Mabel was also personally targeted.

Cathleen: H.L. Mencken, the sort of great American wit, has a famous book called American Language, where he is sort of thinking about how the American language is changing because of all of these immigrants. And it’s a very–he’s writing from this very like superior position of “I am this, you know, very witty man talking about all these immigrants.” And he spends a couple paragraphs making fun of the names of Chinese people in the United States. And he’s clearly going through the Chinese Student Alliance’s magazine and saying like, “Look at all these names where they’re taking on English forms. So like John Wellington Koo, right? This is, this is hilarious.” And he literally names Mabel Ping Hau Lee as one of the people whose names seem so ridiculous.

[Music]

Narration: So before she’s even a full adult, Mabel has been splashed across the front pages of America’s newspapers for her suffrage activism. She’s had a college experience steeped in anti-Chinese racism. And she’s been ridiculed by a famous American satirist. And what about the white suffragists who had invited Mabel to speak and march with them?

In the end, the national woman suffrage movement failed Chinese women. Mabel and her community had taken the time to teach white women how racism—not just sexism—impacted their lives. But white suffragists continued to regard Chinese activists as foreigners, not partners in fighting the common enemy of inequality. So for example, when Mabel was invited to speak to a group of suffragists at a fundraiser for the movement in 1915, her talk was siloed as part of a quote “Chinese week,” and she was asked yet again to update American women on suffrage in China.

[Music Change]

In spite of it all, Mabel continued blazing a trail as a scholar. She finished at Barnard, then earned a master’s degree. And she was working on her doctorate at Columbia University when New York State enfranchised women in 1917. Mabel was still at it in 1920 when the 19th amendment was enacted to outlaw voter discrimination based on sex.

As these suffrage milestones came and went, I imagine Mabel looking up from a huge stack of books for just a moment to register that now second-generation Chinese American women in her community would have a political voice. But as a first-generation immigrant, living under the Chinese Exclusion Act, Mabel still had no path to citizenship or voting in America.

When Mabel finished her doctorate at Columbia in 1923, she was the first Chinese woman to do so. She self-published her 600+ page dissertation, a sweeping economic and agricultural history of China that scholars still reference today.

Finally done with her studies, Mabel weighed her options. As one of the most well-educated women in the country, and maybe the world, what was next for her? Here’s Cathleen.

Cathleen: After getting her PhD, she’s sort of thinking about going back to China and there are very few opportunities for women with PhDs in the United States. There are even fewer for Chinese or Chinese American women and a lot of both Chinese-born women and Chinese-American women end up going to China to work for the YWCA to take up positions in Chinese universities, and to work for the new nation in China.

Narration: So Mabel took an exploratory trip to China and interviewed for a range of different jobs. One of the jobs was Dean of Women at a Chinese university. Another was at a big international import and export company.

When Mabel got back to New York, whatever plans she was making about her future were upended by what was happening at home. Her father had decided to step in between two rival Chinatown organizations called tongs that had been at war with each other on and off for decades. Here’s Reverend Bayer Lee again.

Bayer: At that time, well, you know, different groups edge for power. So the two most powerful tong were the Hip Sing and On Leong. It was self government. They process finance, they gave out loans, they helped immigrants, but they also collected dues so they were almost like the mafia in some way. So these are the factions of the tongs that were fighting. Not only New York but in Chicago and other parts of the country at that time.

Narration: Mabel’s father Towe at this point was a trusted elder of the community. He was president of the Chinese benevolent association, which made him the de facto mayor of Chinatown.

[Music]

Towe set up a meeting between the tongs to try to mediate a truce.

Bayer: So in 1924 he organized this effort. Think about a minister in the midst of a, you know, power struggle between the different factions. But he was booed and jeered. People said, “Sit down, Bible, man. What do you know about anything?” And he was, I guess, struck. Paralyzed. And he died later.

[Music]

Narration: When Towe became ill and died after the meeting, it must have been devestanting for Mabel. He had been one of her staunchest allies. He had supported her education and activist work, and taken pride in all she had accomplished. And while the Lees believed in progressive ideas, that didn’t mean they gave up the traditional obligation of children to respect and care for their parents. Duty to her elders was perhaps even more a part of Mabel’s upbringing then Western individuality. With Lai Beck now a widow alone in New York, Mabel had to decide if leaving permanently for China was the right thing. Here’s Cathleen.

Cathleen: You know, she’s torn between this idea of filial piety, which she talks about how important that is in one of her articles, and her own ambition. And that’s where I think her favorite hymn is a little bit revealing. It says that “I will be faithful through each passing moment. I will be constantly in touch with God. I will be strong to follow where he leads me. I would have faith to keep the path Christ trod.”

Laura: Wow.

Cathleen: To me, I wonder if that’s about this sort of tension she feels between her own ambition and then also right, again, the legacy of the church and what her father had worked for her whole life.

Narration: On top of this soul-searching, Mabel had to wonder whether she could actually have the sort of life in China that had seemed possible when she was a few years younger. The political climate in China had been extremely rocky since the revolution. Coup attempts, assassinations, and divided leaders and provinces, had plagued the revolutionary government.

It was becoming more and more uncertain if China would ever really become a representative democracy. There was so much turmoil that after 1921, no national elections were even attempted until the late 1940s.

Mabel also had to be aware that there was a rising anti-Christian movement in China, among the people and in government. She was still devout, so that had to be a concern.

[Music]

With all of these factors in play, it’s no surprise that ultimately Mabel decided that New York was where she belonged.

Cathleen: The rest of her life is really spent caring for this institution, and caring for the community and the parishioners, who are old enough to remember her, remember her very fondly, as someone who did a great deal of work for their community.

Narration: Mabel took Lee Towe’s place as leader of the Morningside Mission. She led a campaign to buy a building at 21 Pell Street and transform it into a memorial hall in her father’s honor. Inside it, she gathered the community and ministered to them. That building is Bayer’s church, and he continues her ministry work today.

Mabel also grew the mission’s work and offered more and more programs, including expanding educational resources for girls. She took care of her aging mother, and served as a surrogate mom, sister, and daughter to less fortunate community members.

Bayer: These are the personal stories, right? That doesn’t get published, human relationships, that leave a legacy. You know, if you asked me what I think, those relationships are a lot more, you know, a lot more precious.

Narration: On top of her service to the community, Mabel also achieved personal financial independence. She built a sizable fortune as a merchant and property owner, and she was apparently so business savvy that wealthy American families like the Rockefellers hired her as a consultant. Bayer said this was unheard of for a woman in Chinatown at the time.

Bayer: She always appeared to me as an individual. You know, powerful, I mean, to be reckoned with, right? She’s not only a woman but a single woman. As a powerful woman, she’s alone. But she went through the 1918 Spanish Flu. She went through the 1929 Great Depression. Went through World War II. Went through the Communist Revolution. And her last day is with these major leaders in Chinatown, men. And she’s in the center. All the pictures that’s taken of her she’s in the center. Now, how did that happen? Right? She can’t say I want to be in the center of a photograph, right? You don’t do that, right?

Narration: What those photographs signal to me is that Mabel’s leadership was essential to her community. She was a source of internal strength and prosperity, and that was so important when the country outside of Chinatown continued its exclusion and hostility. In 1943, when the U.S. and China became allies in World War II, the U.S. finally slightly loosened their restrictions and some Chinese people could become naturalized citizens and voters. But Cathleen told me how limited that change really was.

Cathleen: It’s like 103 people that, that law and the idea of the quota system and the way in which U.S. immigration was really structured to favor immigrants from Northern Europe, doesn’t change until the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, which, gets rid of the quota system and opens up immigration more broadly and actually changes the face of immigration in the U.S.

Laura: Does Mabel Lee get to vote in her lifetime?

Cathleen: I haven’t found the evidence of that. So, Mabel Lee dies in 1966. In the records for New York, I don’t see her as having applied for citizenship before her death.

[Music]

Narration: So it was only at the very end of Mabel’s life that she saw U.S. immigration policy start to change. But the fact that she never became a citizen was America’s loss, not hers.

From a really young age, Mabel had the global and historical perspective to see that any nation that denies rights and opportunities to some of its population, weakens itself as a whole. She also saw how true this was for the U.S. woman suffrage movement. By marginalizing all other groups, white suffrage leaders weakened the whole fight for women’s rights. They settled for making superficial and incremental changes that benefitted only some, and left the work of achieving true equality to those they had excluded.

So Mabel instead put all her knowledge and heart back into Chinatown. There, she continued to break gender barriers and achieve firsts, without waiting for the right time in the right country. She did so almost entirely on her terms, and while living out her belief that a society is only strong when each beam in its foundation has the freedom to build itself.

Bayer: Remember somebody asked that actress. What’s her name? Emma Watson. She was asked about whether she has a boyfriend or something. And she said I don’t want to be referenced to a man. I’m the reference. Right? You know, women, I’m the reference. I’m not someone’s girlfriend, wife, or daughter or whatever, I’m me. Well, Mabel Lee, perhaps that, that was her argument too, that she is referenced by her. Not even Lee Towe’s daughter, right? She’s Mabel Lee, PhD.

[Music]

Narration: We’re still working on the next episode of Amended, but we’ll be back soon to share it with you. And we’re going to keep exploring the complex relationship between American citizenship and voting. Our final episode looks at Native American activists who fought to have the rights of citizenship while also defending the sovereignty of their tribal nations.

Additional Resources

Guest Cathleen Cahill is the author of Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement, which deftly probes the robust, multi-faceted history of the suffrage movement that has traditionally taken a back seat to the myth of Seneca Falls. Cahill highlights a multiracial group of activists, including Mabel Lee, who pressed for greater inclusiveness in the suffrage movement.

To learn more about Mabel Lee: Read The New York Times’ belated obituary for Mabel Lee, which it published in September 2020 part of its “Overlooked No More” series. Mabel Lee and other suffragists from Columbia University are featured in this article from Columbia Magazine. Visit the National Park Service website and the National Women’s History Museum website for short biographies of Mabel.

To learn more about the history of the Chinatown community, visit the Museum of Chinese in America. Explore the history of suffrage in New York City using this 19th Amendment Centennial story map from Village Preservation.

Our Team

Laura Free, Host & Writer

Reva Goldberg, Producer, Editor & Co-Writer

Scarlett Rebman, Project Director

Nicholas MacDonald

Joseph Murphy

Sara Ogger

Michael Washburn

Episode 5 Guests and Collaborators: Dr. Cathleen Cahill and Dr. Bayer Lee

Consulting Engineer: Logan Romjue

Art by Simonair Yoho

Music by Michael-John Hancock, Emily Sprague, Pictures of the Floating World (CC), Yusuke Tsutsumi (CC), Meydän (CC), and Live Footage.

The work of Mary Chapman, Louise Edwards, Grace Li, and Timothy Tseng helped us immensely in framing our story. Special thanks to Connie Shemo, who consulted on this episode.

Amended is produced with major funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and with support from Baird Foundation, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Phil Lewis & Catherine Porter, and C. Evan Stewart.

Copyright Humanities New York 2021