When the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, a large number of Native American women still could not vote. The U.S. government did not recognize them as citizens. And if having U.S. citizenship required them to renounce tribal sovereignty, many Native women didn’t want it. But early-twentieth-century writer, composer, and activist Zitkála-Šá was determined to fight for both.

In this episode, host Laura Free speaks with digital artist Marlena Myles (Spirit Lake Dakota) whose art is inspired by Dakota imagery and history, and by Zitkála-Šá’s legacy. Dr. Cathleen Cahill, author of Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement, returns to help tell the story of Zitkála-Šá’s struggle for a “layered” U.S. citizenship that included the acknowledgment of Native American sovereignty.

This final episode of the Amended series demonstrates once again how those who have been marginalized within U.S. democracy have worked, and continue to work, to hold the nation accountable for its promise of liberty and equality for all.

Laura: Hi Marlena, Welcome. Welcome to Amended.

Marlena: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Narration: Marlena Myles is a digital artist from St. Paul, Minnesota. She’s Spirit Lake Dakota, and Dakota imagery is central to the art that she makes. When I talked to Marlena remotely a few weeks ago, we both got on YouTube to watch an animated music video she made for a song called “Cinnamon.”

Laura: Do you want to hit play on your end, and I’ll hit play on my end, and we can sort of chat our way through it?

Marlena: Yeah, I can do that.

Laura: Let me know when you’re ready.

Marlena: I’m ready.

Laura: Alright.

[Music starts – Cinnamon]

Tufawon (sings): I think this whole vibe is based on a dream. Huh. But I don’t really know.

Narration: The song was written and performed by Tufawon, aka Rafael Gonzalez, a Dakota, Puerto Rican hip hop artist from Minnesota. “Cinnamon” is a love song, but Tufawon’s music and Marlena’s images also have something important to say about the Twin Cities.

Tufawon (sings): Ooooooh… What smells like Cinnamon? Do you feel that medicine? Do you feel that sense of it right when you step in my room?

Marlena: It starts out with the nature scene. And you’ll see these rain drops on this pond sort of going on with the beats and the music. And you see this Dakota woman, she’s wearing a jingle dress. She’s walking. The skyline of Minneapolis is behind her.

Tufawon (sings): M-I-DOUBLE N-E-A-P-O-L-I-S That is where I be. Double-S- you see.

Marlena: It’s just to show that, you know, this is Dakota Homeland. And when you say things like Minneapolis, Minnesota, you’re speaking Dakota…

Tufawon(sings): …You deserve to see the whole world. You deserve to see the whole world. Whole world and beyond. Oooohhh…

Marlena: Growing up here in Minneapolis, I never saw anything that told me as a kid that this is Dakota homelands, that this urban place is, you know, where my people were from. But as I grew older, of course, I, you know, you learn about history. And I see that this place was very sacred to my people. You know, it’s like the Pike Island here, it’s called Bdote in Dakota. And that’s where we believe is the birthplace of our people. . .You know, I currently live a fifteen-minute walk from that island, so. . .Native people are still here. We still create or exist in a modern way while holding onto tradition.

Tufawon: Give me that love cause I know it lifts me up it picks me up. Give me that plug and I ain’t talking about no drugs…

Narration: Today on Amended, we’ll tell the story of an early-twentieth-century Dakota writer, composer, and activist who’s been an inspiration to Marlena and many others. Zitkála-Šá lived at a time when Native Americans were denied a voice in American democracy, and when forced assimilation was federal policy. Zitkála-Šá fought for equality, autonomy, and for the right of Native American nations to maintain their cultures and pass them on to future generations.

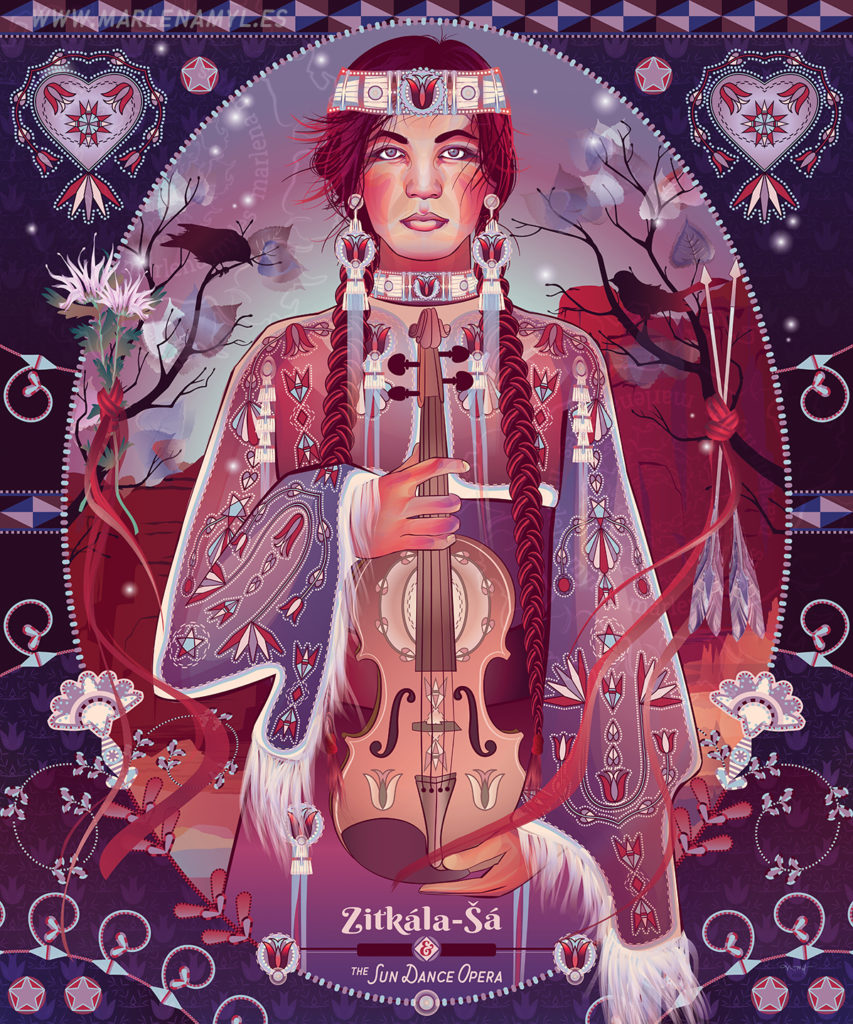

Portrait of Zitkála-Šá by Marlena Myles.

[Music]

Narration: Welcome back. This is the final episode of our series. Over the course of our show we’ve been traveling from the 1800’s to the present day, looking at stories from the struggle for women’s voting rights. Centering women activists who fought not just for gender equality, but against discrimination based on race, citizenship status, and class.

If you’re listening to Amended for the first time, please go back and start with Episode 1. Our series is meant to be heard in order.

Thanks so much for joining us for one last story about what’s been gained, what’s been lost, and what’s still left to be done for women’s equality in America.

[End theme music]

Narration: Before we begin our story, I want to take a moment to talk about names. I introduced the subject of today’s episode as Zitkála-Šá, but the name she was given at birth was Gertrude Simmons. As an adult, she gave herself the Dakota name Zitkála-Šá, which means Red Bird, and used it in published writing, for public appearances, and in some personal letters. She also continued to use the name Gertrude. So rather than using one name or the other, you’ll hear me alternate both.

Okay, here we go. . .

[Music]

Gertrude or “Gertie” Simmons was born in 1875 or ‘76 on the Yankton Dakota reservation in South Dakota. The Yankton nation was one of six different Dakota groups that originally inhabited land that became the states of Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin, but many were pushed westward by white settlers during the nineteenth century.

Gertrude’s mother, Ellen Simmons, was Yankton Dakota and her father was a Frenchman named Felker. At the time, there was a lot of interaction between the Yankton nation and nearby communities of white settlers, including large numbers of European immigrants. As far as we know, though, Felker was never a part of Gertie’s life. Ellen kicked him out shortly before Gertie was born, after he mistreated her son from a previous marriage.

Later in life, when she became a writer, Gertrude would describe her early childhood as idyllic and free. She was surrounded by a loving multi-generational Dakota community and was mostly unaware that her family lived in a state of poverty that had been imposed by the U.S. government.

[Music]

By this point, the U.S. had been displacing and murdering Native Americans for a century, violating treaties and justifying its actions with racist, colonialist ideas. As the U.S. expanded West in the 1800’s, the government carried out a massive campaign to confine Native nations to reservations. When Native American nations fought back, they were brutally attacked by the U.S. Army.

That was the historical backdrop when, about twenty years before Gertrude was born, the Yankton Dakota surrendered most of their territory to the U.S. government, hoping to be left in peace. They were also short on resources, because the U.S. Army had slaughtered the bison that had sustained them for generations. The federal government promised them food and supplies if they gave up their land and relocated.

[Music change]

By the late 1800’s, the federal government changed the focus of its Native American policy. It would force tribal nations to assimilate by converting to Christianity, speaking English, and contributing to an agricultural economy.

Starting in 1887, eight-year-old Gertrude Simmons experienced this firsthand. That’s when Quaker missionaries came to Gertie’s reservation and offered to take her East to get an education. If Gertie went with them, they said, she’d also have all the shiny red apples she could pick and eat. Gertie’s mother saw through these promises and said no at first, but Gertie was enticed. She begged and wept until Ellen gave in.

The next day, Gertie, and a few other children from her community left on a train headed for a boarding school in Wabash, Indiana. The school was called “White’s Manual Labor Institute.” Its mandate was to teach Native American boys to be blacksmiths, carpenters and farmers, while the girls learned to be cooks and housekeepers. White’s got a federal subsidy for each student that today would be worth over $4000.

[Music]

When the children arrived, it was an immediate culture shock, starting with having their long hair cut short. Gertie later described what that felt like, writing, “Our mothers had taught us that. . .short hair was worn by mourners. . .and cowards.” She wrote that she “resisted by kicking and scratching wildly” as she was tied to a chair.

“I cried aloud,” she wrote, “shaking my head. . .until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit.”

[Music end]

Killing the children’s spirit was the goal. And then it was about re-programming them to believe that their own cultures were inferior to the one they were being taught. Their days were tightly regimented, and they were beaten if they fell out of line. They had to learn English and stop speaking their native languages. And the students didn’t just suffer from homesickness and abuse. The school didn’t have indoor plumbing or good sanitation, and it was common for students to get sick. Some were permanently blinded by disease. Some died.

It’s hard to imagine a child coping with so much trauma, and Gertie struggled alone with all of it. “In anguish I moaned for my mother,” she later wrote. “But no one came to comfort me. . .for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder.”

Gertie fought back by breaking a bowl that she was supposed to use to mash turnips. She scratched out the devil’s eyes in a Christian text. With small acts like these, Gertie later said, she was “testing the chains which tightly bound my individuality like a mummy for burial.” The pressure to conform, and the courage to resist, would be with her for the rest of her life.

[Music]

After three years at White’s, Gertie finally returned to the Yankton reservation, but by then it did not feel like home. “I seemed to hang in the heart of chaos,” she wrote later. “Beyond the touch or voice of human aid. . .even nature seemed to have no place for me.”

[Music]

Cathleen: When she goes back home to visit her mother, there’s this real distance between them. . .

Narration: That’s Dr. Cathleen Cahill, a professor of history at Penn State University. You may remember Cathleen from our last episode. Zitkála-Šá appears in her book, Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement.

Cathleen: And that’s absolutely what the federal government wanted to happen. They were, they were trying to sort of break these kinship ties so that native children would not want to live like their parents, right? Wouldn’t have the connection between generations, where they learned the cultural traditions. The goal is within a generation, that Native polities and communities will disappear and have kind of assimilated into the citizenry as individuals who are indistinguishable from other American citizens.

Narration: By the 1880’s, when Gertie first went to school, there were over sixty assimilationist schools, on and off reservations. As the federal government brainwashed and traumatized the youngest generation of Native Americans, it treated their parents and elders like children. A federal agency called the Bureau of Indian Affairs was put in charge of the reservation system. And the Bureau installed white superintendents to manage the land and people. Those who lived on reservations were treated as dependent wards of the state. The Bureau rationed the food on the reservations. Residents had to ask the Bureau if they wanted to leave or have visitors. And it didn’t stop there.

Cathleen: They have to get permission from the superintendent of their reservation to access their bank account, to sell any land, even to sign a lease on their land. So economically in particular, their opportunities are incredibly limited.

Laura: So it’s not just that indigenous people with tribal membership are outside of citizenship. They’re outside of adulthood, essentially.

Cathleen: Yeah. Absolutely. Right.

[Music]

Narration: As a teenager on the Yankton reservation, it was hard for Gertie to envision a future. So in 1890 she returned to White’s School. Maybe it felt like the only place where a kid who had lived in two different worlds could find a path through life.

Back at the school, she studied classical music: voice, piano, and violin. She excelled at writing and at making speeches. And when she graduated in 1895, Gertrude gave a commencement address with a distinctly feminist message. Most of her speech has been lost, but we know she called for “the progress of women” and declared “half of humanity cannot rise while the other half is in subjugation.”

She kept giving speeches when she entered Earlham College in eastern Indiana, one of the few colleges at the time that admitted Native Americans. And as a first-year student there, she was chosen to represent the whole school at a state oratory competition.

On March 13, 1896, at a grand opera house in Indianapolis, over a thousand people gathered. The other speakers, and most of the audience, were white and male. Gertrude approached the stage and shrugged off the racist slurs that the other teams were shouting at her. Then she did something she’d never done before–she openly demanded Native American rights.

Like all the women we’ve heard about on Amended, Gertrude was inspired by the possibility of democracy and equality but found herself excluded from both because of her sex and her race. America’s failure to act on its promises was obvious and personal. The country had begun its “career of freedom and prosperity,” she said, “with the declaration that ‘all men are born free and equal. . .the hope for the future,” lay in “the desire of Native Americans to. . .unite with yours our claim to a common country.”

[Music End]

Most of the crowd applauded Gertrude’s speech, but not everyone welcomed her call for change. When she looked out across the room, Gertrude saw that an opposing team had draped a banner from the balcony just to taunt her. On it was a racist caricature of a Native American woman, with the word “humility” printed at the bottom. It was a rough moment, but Gertrude didn’t let it get to her. Most of the judges ranked her highly, and she came in second in the competition. Gertrude wasn’t just doing this for the accolades. She was learning what it felt like to speak out for justice. “That little taste of victory,” she wrote later, “did not satisfy a hunger in my heart.”

[Music]

We’ll talk about how Gertrude fed that hunger, after a short break. . .

[Break]

Narration: Not long after the state competition, Gertrude dropped out of Earlham College. We don’t know exactly why, but throughout her life she suffered from stomach and lung problems. This ended up being the end of her formal education, but the beginning of a new phase in her life.

Gertrude was a young adult, and she had to think about how to make a living in a society dominated by white people and institutions. So she decided to use her writing and music skills to open some doors for herself. Then, once she was inside, she would take every opportunity to quote “spend her energies” by doing “work for the Indian race.”

First she tried working as a teacher at another boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. This might seem like a strange decision because Gertrude had suffered so much as a student herself. But maybe she thought things would be better at a different institution, or that she could use her authority as a teacher to protect the children there from having an experience like hers. Whatever her reasons for going, it soon became clear to her that Carlisle was no better, and maybe worse. The whole system was a problem.

[Music]

In 1899, after less than two years at Carlisle, Gertrude quit her job. and went to Boston with a grant to study violin from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. There, Gertrude was in the minority as a Native woman, but she found a welcoming community of white artists and writers who encouraged her to write about her life. In her first year there, she wrote three pieces about her childhood and the trauma that Native American boarding-schools were causing. She also harshly criticized the federal policy behind it. Here’s Marlena Myles again:

Marlena: You know, she went through the process of going to these boarding schools but I think when she was there, she saw how Native people were being treated and how their traditions were looked down upon, and that might’ve activated a fire in her to fight back and, I think it made her a stronger person because she was able to advocate for Dakota people and also share our culture and elevate our culture because she was able to walk in both worlds, as they say.

When Gertrude’s writing was printed in a prestigious magazine, The Atlantic, she became the first Native American woman in history to publish her own story without the interference of white interpreters or ethnographers. She also started what would turn out to be a life-long project: writing down Dakota stories that had been passed down through oral tradition, starting with the ones she remembered from childhood. This was also when Gertrude named herself Zitkála-Šá, or Red Bird, to express her Yankton roots.

Zitkála-Šá had an incredibly prolific decade as a writer, and it culminated in a massive creative project that called on all her talents. It was also an act of resistance. In 1910, Gertrude partnered with her friend William Hanson, a white, Mormon music teacher and scholar. And together they spent three years creating a classical opera, the first ever composed by a Native American. They called it the Sun Dance Opera.

[Sun Dance Music Starts, Drumming]

The opera combines Native American drumming and singing with Western instruments and operatic vocals. What you’re hearing is a recent recording of music from the opera that Marlena found on YouTube.

On the surface, it’s a simple love story. But in the show, two male characters carry out a religious ceremony called the Sun Dance. It’s a sacred ritual of music, movement, and feats of endurance that’s been practiced for hundreds of years, by at least twenty different Plains Nations.

[Piano Piece Starts]

In 1884, the U.S. government had banned all Native American religious practices. So if you were caught performing a ritual on a reservation, you could lose your food rations, or even go to prison. The opera subverted this racist law by using a format that white Americans considered high art to perform the Sun Dance openly.

[Operatic Vocals Start]

Marlena told me the opera’s power still resonates with her today.

Marlena: Growing up, you know, I played the flute and I learned the piano. I’ve always enjoyed that genre of music. So to hear that a native person combined our traditional songs on an operatic setting to me was really fascinating.

Narration: Marlena also likes the opera because it portrays the elevated status of Dakota women, in contrast to women’s second-class status in white U.S. culture.

Marlena: You feel that throughout this piece. You learn about the respect of women. Because a Dakota woman back then, they built the house. They owned a house. They would feed the whole family. The whole value of your family came through the woman. So, you know, she placed herself on a high pedestal and she wasn’t just going to have her time wasted by any man.

Laura: Who do you think her audience was for the Sun Dance Opera? Was she trying to reach a white audience, a Native audience?

Marlena: So I guess I could say that the audience was both Native and non-Native people. . .

[Sun Dance Opera – Violin]

Marlena: She found a way to put our religions in the way that they can be taught to a Native person who may be watching, and then the non-Native audience would pick up on, “Oh, this is taking this so-called primitive people. And we’re seeing them in a new light,” perhaps.

Narration: If any of the opera’s white audiences took the opportunity to question their racist ideas, they still probably missed one of Zitkála-Šá’s key messages. When the Sun Dance Opera was first performed in 1913 and ‘14, white Americans had bought into the idea that Native Americans were on the verge of extinction. And so their culture was going to completely disappear. Even the co-creator of the show, William Hanson, referred to Native Americans as doomed to oblivion.

So Hanson thought they were preserving something for posterity. But Zitkála-Šá was using opera to carry the Sun Dance into a future where Native cultures would co-exist along with a white American one. Marlena told me that disguising rituals in white culture was a weapon of resistance for the Dakota people.

Marlena: They banned powwows in early days of reservations. And so the tribes, they would say, well, we want to celebrate Independence Day. Is it okay if we do that with a powwow but we would decorate it in American flags. So you’ll see a lot of beadwork from then that have American flags on it. Like horse masks, regalia bags and stuff. And so the, you know, the, the Indian agent, they’re like “yes they’re becoming good Americans.” But the songs and the dances they were singing were traditional dances. The songs, you know, they’re celebrating beating American soldiers in battle. They’re honoring our warriors in a really traditional sense.

[Music]

Narration: So I want to back up a little bit now, because in parallel with all the artistic work Zitkála-Šá was doing, she also made a life-changing decision: She left majority-white society behind and returned to the Yankton Dakota reservation. One of her goals was to document the oral traditions of her Yankton elders, and she had great success doing that. But she had also hoped to reconnect with her mother, which did not go as well.

Almost right away, it was clear that the damage to their relationship was permanent. And the fights they had must have been pretty hurtful to make Gertrude write to a friend: “I have been needlessly tortured by mother’s crazy tongue ‘till all hell seems set loose upon my heels. and I feel wicked enough to kill her on the spot or else run wild.”

[Music]

Narration: As she struggled with her mother, Gertrude also saw the damage the U.S. government had done to reservation communities. Back in 1887, Congress had passed something called the Dawes Act, otherwise known as “General Allotment.” It declared that all reservation land across the country would be broken up into plots that were “allotted” to each head of household on the reservation.

But as the government carved up the reservations into plots, what it gave to Native Americans was only one-third of the reservation land. It took sixty million acres for white settlers to farm, and to establish national parks like Yellowstone.

Allotment also increased the pressure to assimilate. Most Native lands had been held communally, so dividing them was intended to weaken traditional bonds. It defined men as the heads of most households, which imposed a patriarchy on societies and families. It also forced Native Americans to go into farming–which many had never done–without training or adequate resources. If they weren’t successful, then the only option would be to sell their land.

In exchange for accepting an allotment, supposedly, Native Americans would be granted U.S. citizenship and voting rights. But in practice, it was up to Bureau agents to decide who would qualify. It was impossible to avoid the reach of the Bureau on the reservations. So if you were an activist who wanted to improve the lives of Native Americans, one of your only options was to work for the Bureau.

[Music]

Narration: That’s what a young Dakota man named Raymond Bonnin was doing when Gertrude bumped into him on the reservation. He was a clerk for the Bureau. It was his job to distribute food and supplies on the reservation and help mediate local disputes.

Like Gertrude, Raymond was born on the Yankton reservation, and they had known each other at White’s Boarding School. He had also returned hoping to help his community. Their shared experiences and ideals drew them together, and they got married in 1902.

Shortly after their marriage, the Bureau reassigned Raymond to work with the Ute nation on a reservation in what today is Utah. It would be their home for the next fifteen years. They started a family there, adopting an orphaned Ute boy as their own, taking in a Yankton elder there who had no family. And in 1903, Gertrude gave birth to a son, Ohiya Raymond Bonnin.

[Music]

Narration: Gertrude and Raymond saw the Ute facing many of the same problems the Yankton did: Losing more and more land. Struggling to meet basic needs. They also saw that white Bureau agents on the reservation were taking federal money to enrich themselves. Gertrude and Raymond tried to help their neighbors. She set up a community education center, and he tried to stop white suppliers from overcharging the Ute nation. But white Bureau agents blocked their attempts to make things better, especially as their organizing became more political.

[Music]

Narration: In 1914, Gertrude had joined a new organization called the Society of American Indians, or SAI. It was founded by members of several different nations who were pushing to change federal policy. Gertrude started recruiting local Ute members for the SAI, but she was starting to realize that nothing would change for Native people without confronting the problems on a national scale. “All Indians,” Gertrude wrote in a letter to a friend, “must ultimately stand in a united body for their own protection.”

When Gertrude was elected secretary of the SAI in 1915, the Bonnins decided to quit working for the Bureau and move to Washington, D.C., where the SAI was based. From then on, they would work on a much bigger political stage.

[Music End]

Narration: When Gertrude and Raymond arrived in Washington to advocate for Native American rights, their biggest challenge was the total lack of clarity surrounding what rights Native Americans actually had in the U.S.

Since the 1880’s, the Dawes Act had enabled some Native Americans to become citizens, if they assimilated. But how that was defined varied from state to state. Some tribal nations resisted U.S. citizenship to keep fighting for national sovereignty. Others saw it as a chance to have a voice. Some Native Americans started voting in elections and taking their states to court when their right to vote was denied. Here’s historian Cathleen Cahill again:

Cathleen: All of the Native people that I look at at this time agree that it’s an incredibly confusing moment. Some people clearly have citizenship either because they got it before, or because maybe they were granted it, having taken up their allotment. Sometimes it depends. You can cross a state border and be a citizen in one state, but not in the other. You can cross a reservation line and it will change your status.

Narration: Gertrude was frustrated with this confusion. She wanted the U.S. to pass a law that clearly established Native Americans as citizens. In part, because she began to see voting as a way for Native people to protect themselves and get a degree of autonomy. She debated the issue in public forums. She testified before Congress. And she turned to other women for help.

[Music]

Narration: First she appealed to the wives of Congressmen. Then she noticed the woman suffrage organizations that were out in the streets.

Cathleen: So she lives about three blocks from Lafayette Park, which is where the National Woman’s Party headquarters is. And it’s also right across the street from the White House. And so, I imagine that she is walking by that park and seeing Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party picketing the White House in 1917, 1918.

Narration: So Zitkála-Šá set out to recruit white suffragists as allies. She knew that white Americans in the 19-teens had bought into the idea of the “vanishing Indian,” so she used that to her advantage.

[Music]

Cathleen: For middle class, white American women, there’s something called the Indian craze. And what it is is every fashionable woman has an Indian basket corner in her parlor. So Gertrude Bonnin, she will wear–she calls it a costume herself. But it’s a buckskin dress. She will put her hair into braids. She knows that if she wears this, women’s groups kind of eat it up. And when she gets in front of those women, she uses the opportunity to educate them about what she calls the Indians of today. So she’s clearly contrasting, right? This is your image of Native people, but here’s what we actually face on reservations, where we don’t control our own affairs, where there’s great poverty, where the health issues are devastating.

Narration: Zitkála-Šá argued that Native Americans needed suffrage to protect their rights, just like white women did. So why not work together?

[Music]

Narration: If you’ve heard our previous episodes, what Zitkála-Šá’s doing will sound very familiar: telling white women suffragists that any victory they have will be incomplete if they ignore the fight for racial equality. You might also get déjà vu when I tell you how leading white suffragists responded to this idea. They decided not to waver from their singular focus, even after the Nineteenth Amendment passed in 1920.

Cathleen: The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment doesn’t apply to those Native women who are not citizens, which is a large number of them. And the Native suffragists, right, continue to remind white women of this. The National Woman’s Party actually had a conference in 1921 in February. Thinking about, okay, what do we do next? We have this really powerful machinery, you know, we know how to lobby, what do we advocate for? And they invite a large number of women to speak to them, including Gertrude Bonnin. And Gertrude Bonnin says “not all women have the right to vote, right?” She says, “don’t forget your Native sisters. We need citizenship.”

Narration: But instead of using their new power as voters to push for Native American citizenship, these women turned their backs again.

[Music]

Fortunately, Zitkála-Šá found a more receptive audience in the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, two-million women from service and activist organizations across the nation. They took Zitkála-Šá’s message seriously, and they hired her to tour the country giving lectures.

She made four-hundred speeches over six years, uing the platform to argue that wardship was no substitute for American citizenship. “We seek. . . enfranchisement” she said, “through the help of the women of America.”

[Music End]

This is also when we see a change in Gertrude’s demands. She started to argue that U.S. citizenship alone wasn’t good enough, and that Native Americans needed what she called “layered citizenship.” Which would include the rights and protections that U.S. citizens had, and the right to vote in state and federal elections. But it would not require Native Americans to give up tribal sovereignty, and it would give them the right to elect their own leaders to replace the white agents on the reservations.

By early 1924, these efforts were starting to pay off. Public opinion was changing about Native American rights, and Congress was considering a new bill called the Indian Citizenship Act. It said that all Native Americans “born within the territorial limits of the United states” were citizens.

Some nations, like the Onondaga of New York, rejected the bill because they feared it would threaten tribal sovereignty. And it left white Bureau agents in control of the reservations. But Gertrude saw it as a big step toward autonomy, so she lobbied for the bill. And it passed in June 1924.

Cathleen: So, Bonnin’s excited about this. And she sees citizenship and voting as a real moment of possibility. And so she forms another organization called the National Council of American Indians, she and her husband, Raymond Bonnin found this. And they are clearly hoping to influence politics at the local and state level. And that there can be these Indian voting blocks in States like South Dakota, like Oklahoma, like Montana. And then in the summers, they travel and visit different Native communities. Explaining the Indian citizenship bill encouraging people to participate in voting in local elections.

Narration: In addition to rallying Native American voting blocs, Gertrude and her husband Raymond closely followed any government action that might impact Native Americans. And they had to be vigilant. Right away state governments started using tactics to keep Native voters away from the polls.

Cathleen: White politicians and white residents are concerned that this is going to change the balance of power. And you see them turn to a variety of means of disenfranchising the native citizens in their States. Some of this is very familiar. Kind of following Jim Crow laws, right?. Literacy tests, understanding clauses, things like that. So even though the Citizenship Act has said they are citizens and not wards of the government, some states rule in court cases that under state constitutions, if you live on a reservation and are not paying taxes, you are not considered a citizen and therefore cannot vote. Arizona and New Mexico both rule in 1924 that if you live on a reservation you cannot vote. Montana drops everybody from their registration rolls, and then says you have to re-register.

Laura: This all sounds horrifyingly familiar, in some ways, right?

Cathleen: Yes. Right? No, absolutely. It’s. . .In 2018, we saw in North Dakota, how they targeted native voters by passing the law that said you had to have an actual street address, not a P.O. box, knowing full well that most reservations don’t have street addresses. So these kinds of disenfranchisement absolutely continue up to the present day.

Narration: Gertrude continued to fight for Native people’s voting rights and to rally Native American voters in strategic ways. One of her greatest victories came in 1926.

[Music]

A few years earlier, Gertrude had done an investigation on reservations in Oklahoma. There, white citizens, oil companies, and local courts were colluding to steal from the state’s Native land owners. Oil had been discovered on Native American reservation land, and those who lived there were leasing it out and getting rich.

To separate the Native nations from their wealth, the local courts started declaring some of the tribal members legally incompotent and assigning white guardians to take control of the land and the profits. 4,000 white Oklahomans were in on the scam., and it quickly turned deadly. Over sixty people from the Osage nation were murdered by white guardians who wanted to claim their property. Gertrude and her colleagues published a report on what they found and demanded that Congress take action. After a cursory investigation, Congress dismissed the report as a lie.

[Music]

So when the Indian Citizenship Act passed three years later, Gertrude organized Native citizens in Oklahoma, and they voted out one of the senators who had failed to stop the corruption and violence happening in his state. Gertrude had turned citizenship and the right to vote into effective political power.

A few years after that, Gertrude was totally vindicated. Her Oklahoma report was used as supporting evidence when, in 1934, Congress passed a bill that put a stop to the system of land allotment. It closed the assimilationist boarding schools. It reversed the ban on religious practices like the Sun Dance. And it ended the wardship status of tribal members. That finally restored the right of Native Americans to manage their land and mineral rights.

Although this was an important step, for Gertrude, it was only a partial victory. Because Bureau agents still held their posts as administrators on the reservations, and they still had the right to override decisions tribal leaders made.

After a lifetime of fighting, Gertrude was deeply discouraged that her vision of “layered citizenship” still seemed out of reach. “Though it took a lifetime,” she wrote to a friend in 1935, “the achievements are scarcely visible.”

[Music]

By this point, Gertrude’s health was also declining, and her family was struggling during the Great Depression.

She died on January 26, 1938, at age sixty-one. The autopsy report dismissed her as “Gertrude Bonnin from South Dakota — housewife.” But the two names on her grave at Arlington National Cemetery–Gertrude Simmons Bonnin and Zitkála-Šá–were there to testify to the two worlds she traveled in, and the two worlds she changed forever.

[Music End]

If only we could travel back in time to that moment when Gertrude felt discouraged to show her how much she achieved by resisting assimilation and advancing democracy. We could also show her a beautiful portrait Marlena Myles made of her — in rich blues and reds — as a new cover for her historic opera.

Marlena: You know, I think the work that I create is similar to what she was trying to do. She had the same ambitions that I have, but was living in a place that was not welcoming and had a lot of stereotypes and stereotypical views against her. So. . .

[Music]

… She was a pioneer, I think, in living in those two worlds. Me? Anytime I feel like I’m struggling to find motivation, I guess, to do the work I do, I can always look at what she overcame and I can find strength in knowing that she never gave up.

Narration: I wish all our Amended women had been there to see the year 1965, when Congress passed the Voting Rights Act to block state voter suppression laws. That law marked the culmination of so many movements for change. And yet, I’m also kind of glad they’re not here now to see how the Voting Rights Act has been attacked and weakened in the past decade.

But as they have since the beginning, women activists and organizers keep working to hold America accountable to its highest ideals. . .

[Music Ends / Tufawon – Cinnamon Starts]

My conversation with Marlena was a great reminder that the work of previous generations is always there for us to build on. We just have to be willing to see it.

Before we finished our call, Marlena told me about something amazing that she’s working on now: An augmented reality experience called the Dakota spirit walk. She’s designing it for the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary in St. Paul, Minnesota on the north shore of the Mississippi river.

Marlena: You park the car, you walk underneath this ginormous bridge that connects this cliff to downtown St. Paul, but it’s so far above you that it’s kind of fun to look at, but we walk underneath that. You can also see the river a little in between us and the city skyline. . .

Narration: When the AR experience is ready, visitors will be able to hold up their phones and see Marlena’s animations superimposed over the natural landscape, and hear what the Dakota spirits have to say. It all starts with a colorful flock of butterflies.

Marlena: There’s different colors, but I liked the orange ones the most, and the Monarch butterflies, they say, are your ancestors coming to visit you. So it’s a good thing when you see a butterfly. So the butterflies lead us to the first stop, which is where we’ll see grandmother earth, who we call Unci Maka. There’s a prairie of flowers behind her. She welcomes us to this place. And she lets us know to be mindful of our actions, do no harm, for this is a sacred place, and then we’ll go to stop number two which is a little further down this gravel trail.

Narration: Later on the walk, a giant face appears in the side of a white cliff. It’s the rock spirit, the first and oldest spirit on earth.

Marlena: He’ll talk to us about Kaposia, which is the Dakota village here. And we’ll see sort of the Dakota village life, daily life of activities. So, you know, the women building their teepees. The men working on their tools. But then, you know, he’ll tell us — Íŋyaŋ will tell us– we need to remember and honor the people that used to live here and they’re now buried in the mountains on the cliff above us. . .

Narrative: Before you know it, you get the signal that it’s time to go.

Marlena: And the butterflies will sort of surround you and like do a little fluttering dance and they will disperse. And you’re left to take the knowledge that you gained on this path with you, and maybe in your daily life be a better relative to the earth and to each other.

Laura: What a wonderful way to weave together the present, the past, the meanings, the ways that people have engaged with this space over time, how we’re engaging with space now.

Marlena: Yeah. And for me, I think augmented reality is like the perfect metaphor for Native presence, as I like to say. Because our stories, you know, our philosophies are here embedded in these places. And I want people to go there and feel the power. You know, I think that will open their eyes to what’s here.

[Music Change]

Narration: Amended was recorded on Haudenosaunee, Seneca, Cayuga, Susquehannock, Nentego, Piscataway, Lenape, Osage, Shawnee, Wabenaki, and Dakota lands. We offer our thanks to our Native hosts, both past and present.

This was our final episode. Thank you for helping us reach more people than we ever dreamed possible by sharing this show with your friends and family. I hope what you heard here inspires you to stay curious about history, and how it defies simple narratives. And I hope when you hear a story about an important time or event, you always remember to ask “who else was there”?

Additional Resources

Guest Cathleen Cahill is the author of Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement, which deftly probes the robust, multi-faceted history of the suffrage movement that has traditionally taken a back seat to the myth of Seneca Falls. Cahill highlights a multiracial group of activists, that includes Mabel Lee (Episode 5) and Zitkála-Šá (Episode 6).

Guest Marlena Myles is a St. Paul-based digital artist whose art is inspired by Dakota history and imagery. Explore her work on her website.

To learn more about Zitkála-Šá:

Watch these beautifully animated short videos: This documentary from Unladylike 2020 is a wonderful depiction of Zitkála-Šá’s life and activism. This short film by Yvonne Russo highlights Zitkála-Šá’s musical creativity. It’s part of “Discovering New York Suffrage Stories” from WNED. Both projects were supported by Humanities New York grants.

Our Team

Laura Free, Host & Writer

Reva Goldberg, Producer, Editor & Co-Writer

Scarlett Rebman, Project Director & Episode Co-Writer

Vanessa Manko

Sara Ogger

Michael Washburn

Episode 6 Guests and Collaborators: Dr. Cathleen Cahill and digital artist Marlena Myles

Consulting Engineer: Logan Romjue

Art by Simonair Yoho

Music: “Cinnamon” by Tufawon, Sun Dance Opera clips from a documentary by Palisander Verlag, Michael-John Hancock, Emily Sprague, Pictures of the Floating World (CC), Yusuke Tsutsumi (CC), Meydän (CC), and Live Footage.

Sound library: Freesound.org

The work of Susan Rose Dominguez, Karen Hansen, and Tadeusz Lewandowski helped us immensely in framing our story.

Amended is produced with major funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and with support from Baird Foundation, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Phil Lewis & Catherine Porter, and C. Evan Stewart.

Copyright Humanities New York 2021