Humanities New York sits down with Josie Whittlesey of Drama Club and Cameron Rasmussen and Ryan Burvick from the “Beats, Rhymes and Justice” program. They discuss the Action Grant-supported projects they offer to incarcerated youth (men and women under the age of 21) on Rikers Island.

HNY: Rikers Island sounds like a difficult place to get an educational program going. How did you start it?

Josie: I started with one class at the Robert N. Davoren Complex. It took a long time to get invited in. When I finally got there, it was just a matter of doing a weekly class and constantly checking in with the youth and figuring out what they needed. What was working for them and what wasn’t working for them, and then trying to replicate that.

Cameron: I work for the Center for Justice at Columbia University. Ryan works for a music production company called Audio Pictures. We partner on “Beats, Rhymes and Justice,” which is part of a larger set of programs called the Rikers Education Program. We’ve been doing programming for a little over two and a half years. “Beats” was the first program we did together. The Center for Justice got connected through the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. We went in, met some guys, asked them about what they wanted. One of the things was beat-making. We were able to connect with Ryan, and the rest is history.

Ryan: I founded Audio Pictures back in 2008. It was a neighborhood studio for the poorer communities, in the west side of Queens, Long Island City Area. A lot of the residents from the projects would come to the studio and express themselves and record. Over the years I started working on iPad curriculums to bring [a mobile recording studio] to after-school programs. Then I linked up with Cameron, and it was the culmination of ten years of studio work. We had some insight as to what people wanted and knew how to get professional quality with a small device.

When I started doing this work with “Beats, Rhymes and Justice” and the Center for Justice I actually thought it was going to be a one-program cycle, which consisted of maybe four or five classes spread apart every Saturday. I just thought I’d give it a try. I didn’t realize how much I would care. I didn’t realize how much I would fall in love with the work and the people I would meet.

HNY: What obstacles do you face in running this program?

Josie: One of the biggest obstacles when we start each program at each site is getting staff buy-in. I feel like we actually win over the kids pretty quickly, but to win over the staff takes a little longer. We have to prove that we’re safe and that we’re just trying to support a healthier environment, giving the kids the chance to have fun and communicate with each other. Luckily we’ve met some amazing correctional officers and people in the jail that do support us.

For the “Pivotal Rights” performance [at the Rose M. Singer Center], we asked one of the correctional officers who works with us a lot to play a little part. The girls just totally jumped on the wagon with that and said “Come on, you have to do it!” She did, which was amazing. The cool part of it was that she actually went home and did research. She played one of the men in Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet who was trying to convince him not to give women the right to vote. She researched what arguments men of that time were using to deny women the right to vote. It was really cool.

Ryan: For me, the day-to-day stuff or politics of Rikers Island doesn’t seem like an obstacle. The obstacle for me once we actually get to the room is reminding the young men and women who they are. Everything about their environment breaks them down. We use the tools of the program as a way to remind them of what they’re capable of. It always feels like it’s not enough time to get the point across. You hope that you’re leaving a lasting impression.

Cameron: Jail is a very unstable place. People who are incarcerated there have a lot of instability in their lives, and who knows what’s going on. There’s a lot of stuff that they’re dealing with. Their readiness to be in an educational space [varies]. The music generally gets them ready pretty quickly.

HNY: How do you create a safe learning environment for the students in your programs?

Ryan: I try to make the environment very natural. My goal is to treat them like I saw them right around the corner in my neighborhood, like someone who came upstairs to do a recording session. I create an environment that is hopefully filled with some wisdom, some games, some information, some knowledge that they can take with them. I think creating a space that is very family-oriented and street level has helped me gain the trust of the students that I’ve been working with and has spread to my counterparts.

Setting up an environment where we assume that you’re going to be great allows for any of these other topics—whether it be something about mass incarceration or something about how you conduct yourself as your personal being—to run smoothly.

Josie: We’re all teaching artists, we’ve all taught in multiple spaces. This is another classroom. We greet them with respect. We try to create an ensemble, which is very much part of theatre. The kids feel it’s a family. It’s a safe place. It’s physically safe, and it’s emotionally safe. Those are two things they don’t get in jail.

HNY: How do the humanities inform your programs?

Cameron: A lot of our work is thinking critically about social justice and justice systems. [We help participants] to understand not only their own experiences but also the larger forces and systems that exist in this country, situating themselves inside of that. That sometimes happens through lessons and discussion, but a lot of time through music. We use hip hop songs to unpack not just hip hop itself but also lots of issues that young folks face, that people face in general, many of which are centered around issues of justice.

Josie: The teaching artists are always talking about meeting these kids where they’re at. For a lot of them, the idea of extending themselves to something they really don’t have any experience of was challenging. The Action Grant allowed us to look at the suffrage movement and really study it together. I came into it not really knowing as much about the suffrage movement as I should, and I tried to educate myself and then bring that to them. I watched these young women put themselves in the position [of the suffragists] to understand why they would make such intense sacrifices in their life for a woman’s right to vote. Without the Action Grant, we never would have gone on that really challenging but really rewarding journey.

HNY: What are the short and long term benefits of opportunities like this, in your opinion, for incarcerated people?

Ryan: I would say off the top: better quality of life. Getting people to work and engage with each other, and having a space where they can create and perform and express themselves openly, brings everyone in that community together—the people that work there along with the people that are housed there. I think that also creates a more productive environment, an environment where other things can be negotiated, other privileges and other aspects of how they conduct themselves.

Josie: They also learn to trust education. Education doesn’t just mean sitting in a classroom being bored out of your mind, and feeling disconnected from whatever subject you’re trying to learn. It’s expanding what education can look like.

Ryan: They’re actually realizing that education is a tool that they can use. It can help lead them in the direction that they really see themselves going. When people like Josie and Cameron come in–dynamic, intelligent people who have a lot of life experience under their belt–it changes not only how they view education but how they view the person delivering education. It creates a different concept of the teacher. It inspires them one day to even lead a group as well.

HNY: What’s something you’ve learned from the students?

Ryan: I learn something new every time. I’ve learned that when you open yourself up to a smile or to a hug, and when you just show up to give yourself a chance to succeed, life works with you. Sometimes I don’t want to show up because it’s an obstacle to get there. But when I get there, I’m always glad I did. It teaches me a lot about how to live life.

Josie: I think it’s very powerful that artists get to go into these spaces. It’s obviously teaching us a lot about our world. I really had no idea about what was going on with mass incarceration before I started working in jails. I get to connect with people I wouldn’t usually get to connect with. It’s a privilege. On a basic level, I feel like I’ve made some really beautiful friendships, even though I know they’re youth. There’s a real bond of communion when you’re in those spaces together.

Cameron: The bigger thing is how much I don’t know. We exist in a world, and especially a country, where we’re supposed to know things. We’re supposed to be experts. As someone who hasn’t served time in jail or in prison, there’s so much I don’t know. The other piece of this is the amount of stuff that these folks are dealing with and the fact that they can still come and be kind and have fun and laugh and engage critically. It’s pretty amazing.

HNY: What role can the humanities play in reducing the number of Americans behind bars?

Josie: Funding programs like this is pretty powerful. The students wouldn’t have done this project without that grant. The young women learned something, and they internalized something that wouldn’t have happened without that money.

Ryan: They probably would have been doing just nothing. That’s really the alternative to the programming: nothing. Sitting there with an idle mind. More money can help to bring some of the best minds into these spaces. There’s something the scholastic community can also gain by opening themselves to this population of people who are forgotten.

Cameron: I want to zoom out a little bit. Fundamentally we’re talking about changing the way that we respond to behavior we deem harmful. What does it mean to support people who are in conflict with themselves or others in a way that’s actually about helping them heal? There’s certainly a lot of variables, but a lot of this is the way everyone thinks about and understands justice and morality and punishment, and what our own beliefs are about what should happen when someone does something that is wrong or harmful. The more that we can have critical or open conversations about what those things are, the more likely there will be at least a better understanding. The humanities can help get people closer to these issues, both through discussions and also through creating cross-dialogues between people who are impacted and people who are not. Having critical discussions about justice, punishment, and morality I think are worthwhile efforts.

HNY: What projects are you working on now?

Ryan: I’ve started thinking more about reentry. There’s a need to continue the same type of energy we give to them inside, outside. I am really thinking about ways to continue the programming in the same intimate and creative environment that we’re allowed to do when we’re in there. Most recently I got the opportunity at Rosie’s [The Rose M. Singer Center] to create something called the Free Studio, about Audio Pictures the production company. It’s for free minds, free styles, and free thinkers. It’s a play on the word freedom, but it’s also a place where they don’t have to pay for anything, and they can experience a wealth of information for free. We’ve done six weeks straight at Rosie’s, and it went pretty well. Hopefully that can lead into some sort of reentry program and can reach the world.

Josie: We’re working on that, too. It’s very difficult. We do a partnership with The Door in Lower Manhattan. We’ve been able to pull a few of them [the Rikers students] in, and we give them a paid internship to come and help us teach a weekly class there. It’s an opportunity for them to step into a space where they do have some expertise. I’m thinking about that all the time–how can we grow it, how can we expand it, how can we really serve them when they come back home?

Cameron: “Beats, Rhymes, and Justice” is still going strong. We partner with Columbia faculty, graduate students, and community organizations that develop courses and bring them in. We have a creative writing thing happening next month, we just launched a game design course. We’re sort of thinking about how can we use the talents and interests and capacity of people at Columbia in particular, but also folks in the community, to support people’s education and their critical thinking.

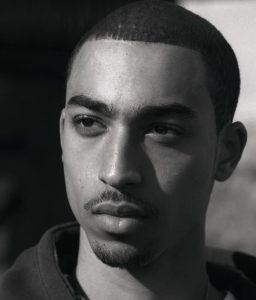

Interview of Ryan Burvick, Cameron Rasmussen, and Josie Whittlesey by Scarlett Rebman, Humanities New York. Photo credit: NYC Department of Correction.

- For podcast episodes featuring the work of Drama Club and Beats, Rhymes and Justice, visit The Takeaway and The Documentary.

- Follow @DramaClubNYC on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

- Follow @JusticeColumbia on Twitter and @JusticeInitiativeatCU on Facebook.