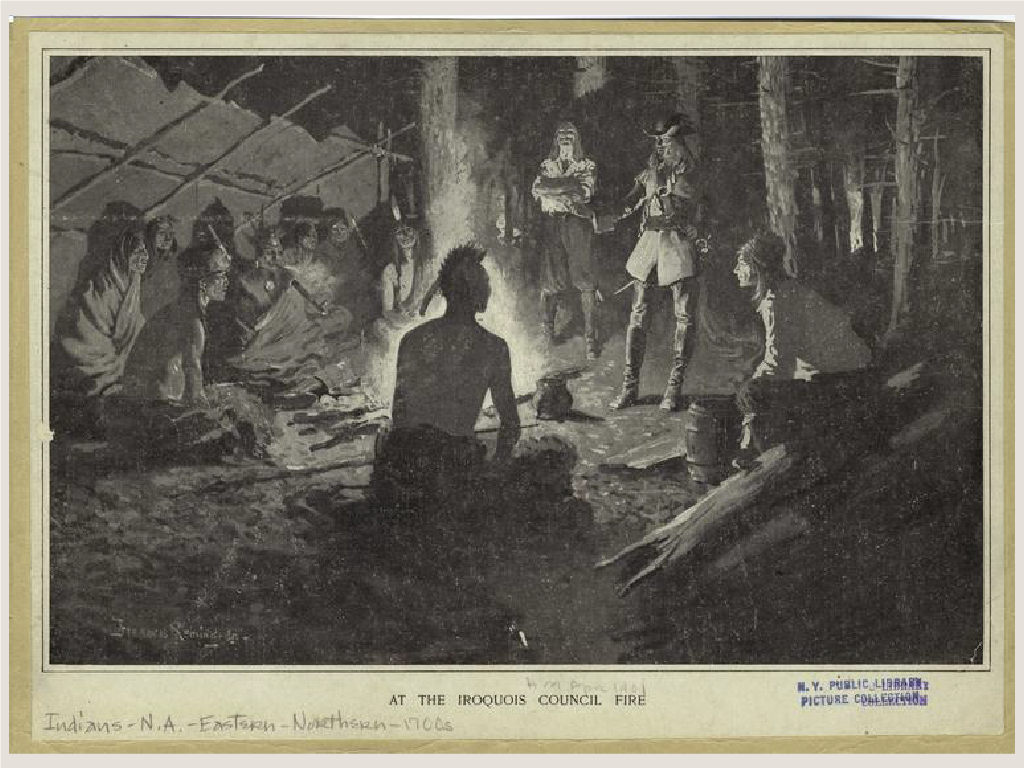

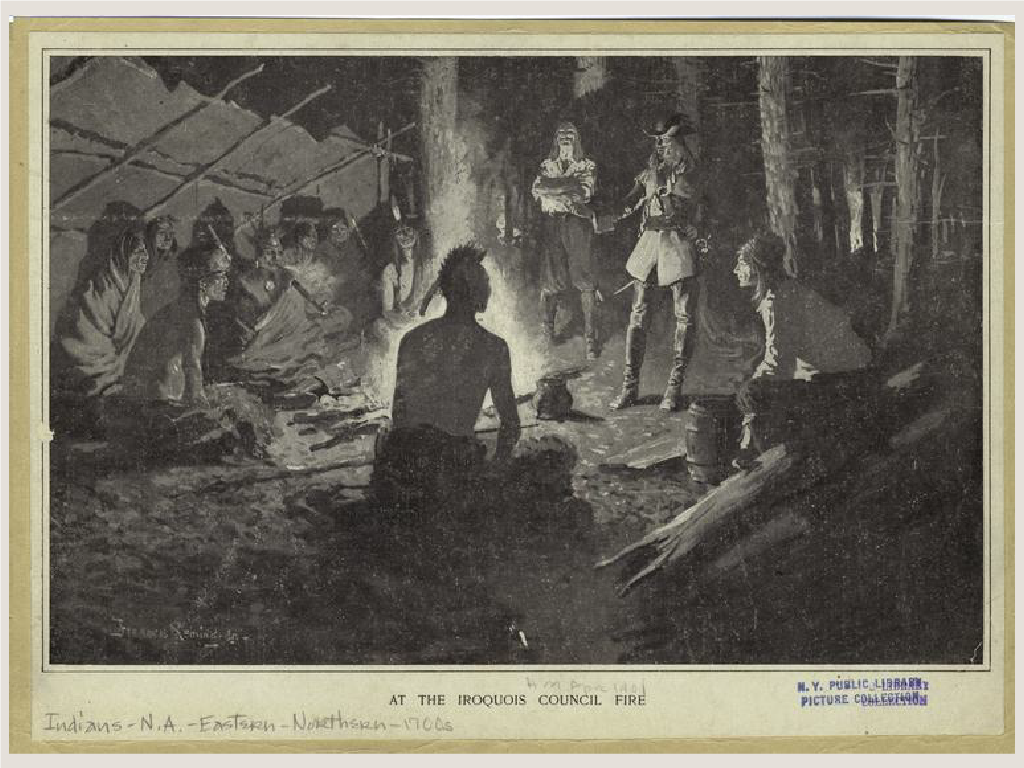

At the Iroquois Council Fire painting by Frederic Remington c. 1901. Courtesy New York Public Library.

In advance of HNY’s April event featuring Ned Blackhawk and Nicole Eustace in conversation, we’re diving into the authors’ work. Read on for excerpts and analysis from Blackhawk’s National Book Award-winning The Rediscovery of America and Eustace’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Covered with Night.

“Indigenous histories invite new interpretations of American history,” Ned Blackhawk writes in The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History. Acknowledging the “currents of deaths and disease” that rippled through the continent in the wake of European settlement, he offers a counter-example with the Iroquois Confederacy: an alliance of five Haudenosaunee-speaking nations that gained economic, social, and political leverage throughout the 17th and 18th centuries that made them intermittently more powerful than colonists. Though among the “most feared combatants of early America,” preserving peace was a foundational tenet of their union.

Blackhawk writes of the diplomacy practiced within the Confederation and the strategic advantage it granted its member-nations:

Archaeology, documentary records, and oral histories reveal the formation of a Great League of Peace in the pre-contact era when five different nations—the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca—united around a set of teachings, rituals, and practices. At the time, such unity quelled strife between discordant villages and positioned the Iroquois to better harness, compared to other Indian nations, the violent advantages of contact. They shared a system of clans and chieftainships, representative councils, and governing practices including the annual recitation of beaded wampum belts that recorded Iroquoian epics and philosophies. Using shared values and ceremonies for peace, by 1600 the Iroquois had developed a confederation capable of withstanding the turbulence of contact.

Long-standing practices of organized governance equipped them to conquer or form unions with tribes and settlers. That said, “By the [17th] century’s end, “Iroquois soldiers would leave their villages more often to talk than to fight,” as Blackhawk notes. They acted as emissaries in a form of “shuttle diplomacy” that granted them invitations to colonial and European capitals.

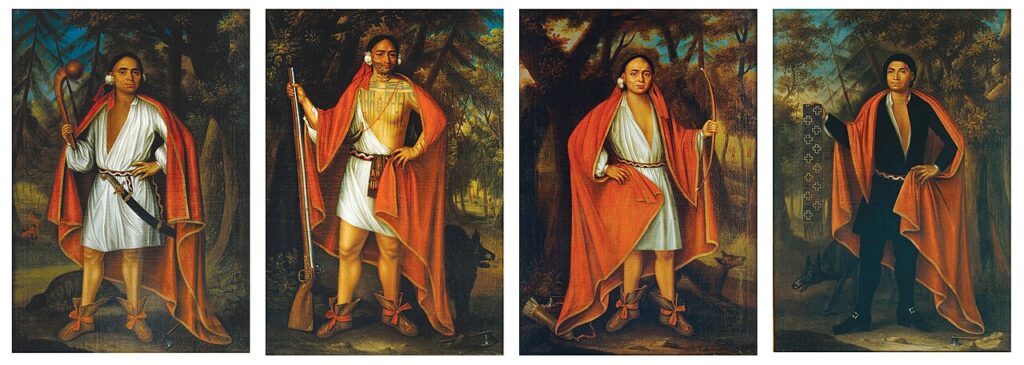

Four Indian Kings by John Verelst (Johannes Verelst), 1710. The honorary portraits were painted during a diplomatic visit to the Court of Queen Anne. Public Domain.

But for the Haudenosaunee, diplomacy was more than a means to curry favor among settlers and overseas royalty—it was a practiced belief worth fighting for. In Covered with Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America, Nicole Eustace recounts how the Haudenosaunee successfully campaigned to inscribe their ethics into colonial—and later U.S.—law.

Covered with Night portrays in rich detail the death of a Seneca man at the hands of two English settlers and its momentous aftermath. Anxious to avoid outright war, colonial leaders pushed for justice to be served to the fullest extent, even if it meant capital punishment. But to their surprise, the Haudenosaunee advocated for clemency for the perpetrators. Negotiations culminated in a meeting in Albany among Haudenosaunee elders and governors from New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, where the Great Treaty of 1722—the oldest continuously recognized treaty in U.S. history—was drafted.

“Indigenous ideals entered the record made at Albany almost inadvertently, Eustace writes in Covered with Night. Nonetheless, their records “preserved Indigenous ideas on crime and punishment, violation and reconciliation.”

In a New York Times essay, Eustace makes the case for the Iroquoian Confederacy’s influence on justice systems at home and abroad today:

What’s distinctive about the Treaty of 1722 is the alternative approach it offered to creating a fair society, one in which people who commit crimes can later be reintegrated into the community — and one in which a crisis of violence can be resolved without inflicting further harm. The treaty provided a working model of restorative justice, demonstrating how communities of the victims and the perpetrators of a crime can come together to repair social relationships through economic, emotional and spiritual offerings. The story has applications today, demonstrating that criminal justice reforms that may sound radical now, as they are pursued by a wide range of community activists, researchers, educators, legislative reformers and progressive jurists, actually have a long American tradition.

As Eustace puts it in other words in Covered with Night: “Colonial magistrates could not imagine the possibility that the Indigenous ideas they were encountering would endure for generations, dormant seeds awaiting the right moment for renewal.”

The moment has yet to come for those seeds to flourish. Eustace and Blackhawk’s work reminds us of the work that’s been done—and that’s yet to do—to cultivate more humanistic attitudes towards conflict.

Purchase tickets: