By Alison K. Lange.

For as long as women have battled for equitable political representation in America, those battles have been defined by images—whether illustrations, engravings, photographs, or colorful chromolithograph posters. Some of these pictures have been flattering, many have been condescending, and others downright incendiary. They have drawn upon prevailing cultural ideas of women’s perceived roles and abilities and often have been circulated with pointedly political objectives.

An excerpt from Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement

In the mid-19th century, female reformers faced an impossible task as they advocated for rights and aimed to maintain a high social standing. Women who had the means to live up to ideal femininity, but chose not to, prompted anxiety. Ultimately, one of the main tasks of the women’s rights movement was to justify their steps outside accepted gender roles and, eventually, change these roles. But without power, money, or organizational strength, activists could not change the way Americans conceived of political women. Cartoons that derided reformers proliferated during the years after the Seneca Falls Convention. Artists continued the tradition of representing political women as ugly, masculine threats to American values, including gender norms, white supremacy, and heteronormativity.

The women’s rights movement grew out of women’s activism on behalf of other people. In the 1830s, women, especially white middle- and upper-class women, participated in and led antislavery and moral reform societies.[i] They signed petitions, raised money, and read the Liberator. Abby Kelley Foster, the Grimké sisters, and Lucy Stone traveled the country to deliver public lectures.[ii] Rather than leading organizations, they hoped to leave behind towns of supporters who organized on their own.[iii] By the end of the decade, their outspokenness angered even their fellow antislavery supporters. In 1840, the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London, for example, refused to seat female attendees.[iv] Discussions of women’s rights were part of local conversations years before women brought them to the national stage. In 1844, a group of men in New Jersey petitioned the state constitutional convention to grant women the vote.[v] Two years later, three groups petitioned the New York constitutional convention to enfranchise women.[vi] One, a group of women from Jefferson County, asked for more than the ballot. They wanted “to extend to women equal, civil and political rights with men.”[vii]

In July 1848, about three hundred people, including prominent abolitionists Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass, met in Seneca Falls, New York. They sparked national conversations about women’s rights and set an agenda. At the end of the two days of proceedings, one hundred attendees signed a statement of their aims, the Declaration of Sentiments.[viii] The main author was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a thirty-two-year-old highly-educated mother. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, her Declaration of Sentiments affirmed that “all men and women are created equal.” Attendees called for rights ranging from women’s education and employment opportunities to the right to own property and control their money. Reformers included the right to the ballot, which they viewed as a tool to gain other rights and enact temperance and antislavery laws. In 1851, the attendees of the convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, resolved that “the Right of Suffrage for Women is, in our opinion, the corner-stone of this enterprise, since we do not seek to protect women, but rather to place her in a position to protect herself.”[ix] They addressed their opponents’ arguments, which contended that fathers, husbands, and sons represented their female counterparts.

Unlike petitions to local governments, the Declaration of Sentiments established specific goals to launch a movement. Stanton’s document asserted, “We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf.” They wanted their meeting to prompt “a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.”[x] Between 1848 and 1860, they held national conventions every year (except in 1857).[xi] Organizers concentrated their national meetings in the Northeast and Midwest, but local groups held gatherings throughout the United States.

Public calls for women’s rights prompted a backlash. Artists, editors, and publishers seized upon fears of political women and produced a powerful new wave of cartoons to caricature them.[xii] They policed gender roles and undercut reformers. In 1849, David Claypoole Johnston, a popular engraver based in Boston, published a page of five scenes in his periodical, Scraps (see figure ).[xiii] His cartoons exemplify the negative press that plagued activists. One picture on the top right, Women’s Tonsorial Rights, depicts a woman about to be shaved in a barbershop. To her right, a woman stands in an unladylike manner with her hands in her coat pockets and a cane propped against her chair. Another female customer reads the Woman’s Rights Advocate newspaper as she sits with her feet up on a chair. On the left, a woman shaves her face. The scene recalls pictures of barbershops filled with men, with their hats and canes set aside, socializing as they are shaved.[xiv] Even the picture hanging on the wall depicts female boxers. Johnston’s other images reveal that these scandalous women might feel empowered to propose marriage and smoke in public. He suggested that women would become like men physically and usurp men’s separate spaces and rites if they gained rights.

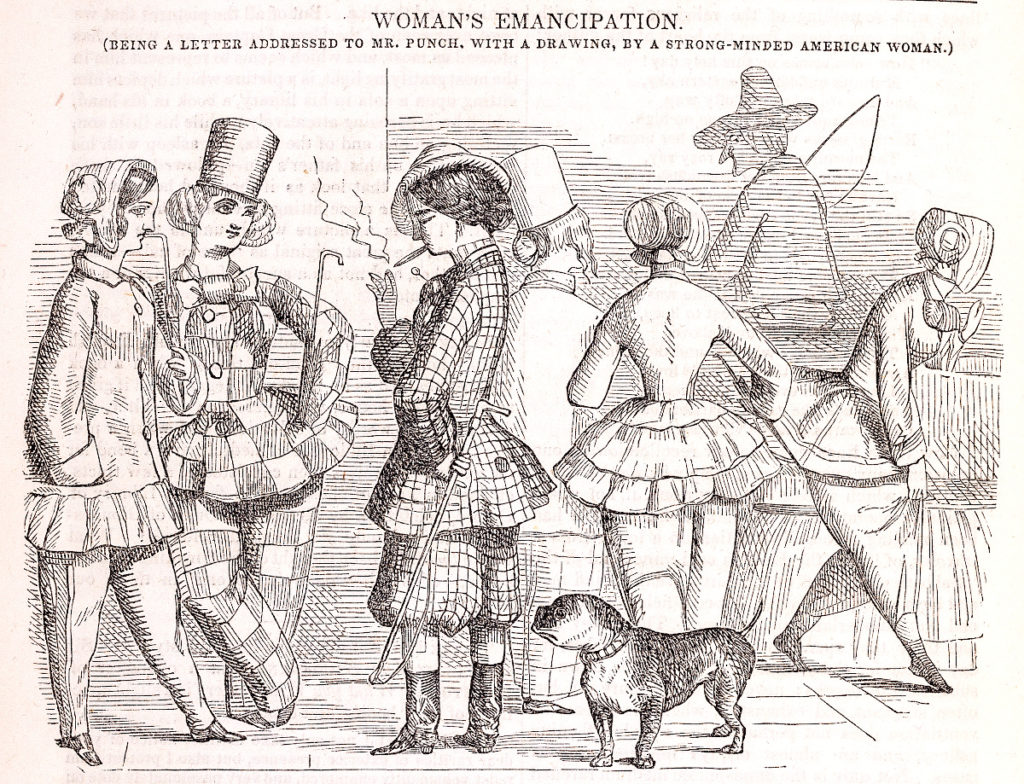

Artists and editors presented the movement as a ridiculous threat to established values. Similar to Johnston, in August 1851, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, aimed at an educated Northern audience, combined several of these sexist tropes into their engraving called Woman’s Emancipation (see figure). The illustration depicts six women wearing bloomer styles with top hats or bonnets, carrying canes, and smoking. The bloomers have short skirts, much shorter than those actually worn, and one woman on the right pulls up her pant leg, boldly revealing an ankle. Another woman on the left wears a bulky overcoat with her hands in her pocket in a relaxed, masculine stance. The only man in the picture wears a broad-brimmed hat and holds a whip, an allusion to true manhood. He turned his back to the women and rides away hauling a cart; perhaps he is a farmer who has just finished his dealings in town. He is leaving the city with its “emancipated” women for a more traditional rural community. Two of the women link arms, perhaps a suggestion of their preference for female partners, and watch him go.

An accompanying satirical letter underscores the idea that political women challenge values ranging from gender norms to heteronormativity. The letter, supposedly written by the “strong-minded American woman” Bostonian Theodosia Bang, declared that women were emancipating themselves from the “feudal” systems, symbolized by the term “Lady,” and from traditional “European” clothing. Bang continued, “The American female delivers lectures, edits newspapers, and similar organs of opinion” so that the “degrading cares of the household are comparatively unknown to our sex.”[xv] Emancipated women were distinctly American, and the fictional character announced that she planned to proclaim these ideas in Europe next.

Artists, editors, and publishers expected audiences to laugh at these women. Without context, to twenty-first-century eyes, pictures of women living nontraditional lives might suggest that Harper’s Weekly supported women’s rights. Today, Americans regularly see images of women smoking, wearing pants, and taking part in same-sex relationships. However, knowledge of the era’s visual context makes the ridicule apparent. Neither cartoon represents the reformers as respectable women. Scraps was a comic publication, and the satirical letter in Harper’s Weekly’s clarified the picture’s message. Women’s rights supporters were easy targets and subjects for entertainment since most Americans opposed their cause.

In their pictures, artists stressed that gender equality would lead to racial equality. Pictures most often lampooned the white women who tended to hold the most visible positions. However, some artists noticed the emergence of black female reformers, such as Maria Stewart, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Forten Purvis and her sister Margaretta Forten. One print, published in 1851 in New York City, was part of a satirical series that featured multiple plates about women’s rights and dress reform (see figure).[xvi] This lithograph, entitled Bloomerism in Practice: The Morning after the Victory, depicts two smiling bloomer-clad reformers. The white woman, wearing a knife, holds a sign that says “no more basement and kitchen!” with a fork at the top of the pole. The black woman’s sign reads “no more massa & missus.” It implies that if white women abandon their domestic work, then black women will resist enslavement and oppression too. These women are eager to fight for Mrs. Turkey, seated in the center, to become president. Her name, the turban, and the water pipe reference a popular alternate name for bloomers: “Turkish dress.” This female politician abandoned her child, who wants his breakfast. Mrs. Turkey pets her husband, who hunches over like an old woman and mends his coat. Society praised women for their domestic tasks, but the same chores degraded men. An earlier plate in the series notes that he wears bloomers too, per his wife’s orders.[xvii] Bloomerism was more than a fashion, the cartoons said; it was dangerous.

By 1851, Americans had encountered images like these for almost a century. Images showed audiences a future that many feared. If women won rights, then black women would as well. One shift in the hierarchy would endanger the entire social and economic system. Women’s rights even threatened to tip the balance in debates about slavery and white supremacy. Since Americans conceived of political power as masculine, manly women’s rights activists fit established visual conventions. To maintain a balance, men, opponents posited, would need to become feminine, take on more domestic responsibilities, and heed their wives’ orders. Rather than create fresh commentary, artists relied on familiar visual tropes to keep women in their place.

In 1845, thinker Margaret Fuller bemoaned cartoons like these in Woman in the Nineteenth Century. The transcendentalist book rejected the dominant gender norms. Fuller observed that opponents contended that if women became political, “The beauty of the home would be destroyed, the delicacy of the sex would be violated, the dignity of the halls of legislation degraded.” This fear, Fuller argued, resulted in the “ludicrous pictures of ladies in hysterics at the polls, and senate chambers filled with cradles.”[xviii] In response, she countered that “woman can express publicly the fulness [sic] of thought and creation, without losing any of the particular beauty of her sex.”[xix] Unfortunately, reformers lacked any power to prove Fuller’s point.

Fuller knew that graphic satire damaged impressions of female reformers. Pictures most often disparaged women as a class, but sometimes they lampooned specific reformers. Even before listeners went to see Lucy Stone lecture, they had a negative stereotype of her in mind. Stone encountered angry audiences when she started lecturing in 1847. Once, a man with a club protected her from an unruly crowd, but other times the audience launched eggs, spitballs, and even a hymnal at her.[xx] Crowds disliked her message, but they also disliked the messenger. An 1853 engraving in the Illustrated News (a short-lived publication by showman P. T. Barnum), supposedly copied a photograph by Mathew Brady. Stone appears in bloomers, short hair, and a frumpy jacket, reinforcing the idea that she appeared masculine.[xxi] Two years later, Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion commented, “Lucy Stone is lecturing on the subject of woman’s rights in Michigan. Her appearance is said to be quite manly.”[xxii] In response to criticisms like these, reverend and women’s rights supporter Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote in a suffrage tract, “Lucy Stone said, ‘woman’s nature is stamped and sealed by her Creator, and there is no danger of her unsexing herself, while his eye watches her.’”[xxiii]

Popular pictures criticized women who wore bloomers, but they also made fun of women who wore fashionable dresses, suggesting they were incapable of rational thought.[xxiv] Clothes served as a visual signifier for gender, class, occupation, and country of origin.[xxv] In the early 1850s, American women increased the circumference of their skirts by adding layers of heavy petticoats. European fashions often influenced American styles, and magazines like Godey’s Lady’s Book kept moneyed women aware of the latest styles.[xxvi] The tightest corsets and most voluminous skirts signified a woman’s elite social status. Farming, domestic and factory work, exercise, and travel were challenging in such clothing. Even Southern slaveholders invested in dresses and petticoats for enslaved women, though trousers would have kept them safer as they tended kitchen fires.[xxvii]

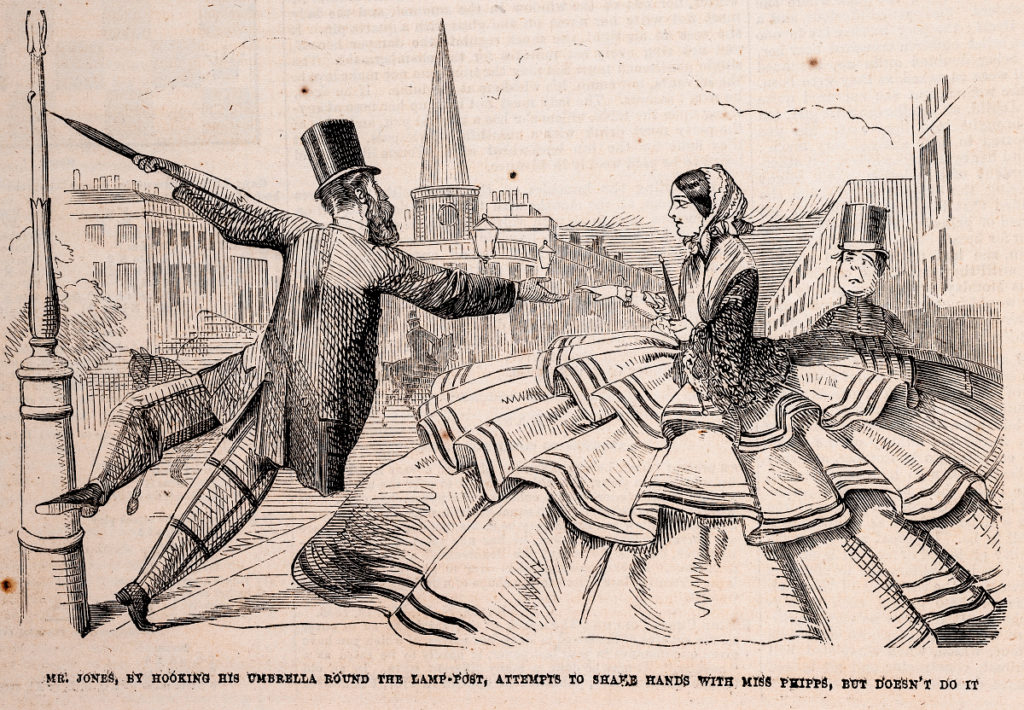

Popular pictures reveal that fashionable women provided as much entertainment as women in bloomers did. In 1856, the introduction of the crinoline, a skeletal undergarment resembling a cage, made skirts even wider.[xxviii] Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, priced at six cents, included scores of images between 1857 and 1864 that mocked the crinoline (and more ridiculing other women’s fashions). In an 1857 engraving, a man wraps his umbrella around a lamppost in an attempt to shake hands with a woman wearing an expansive, tiered skirt (figure 2.10). Her dress separates her from the man and, implicitly, from society. On the right, a man looks at the scene in disbelief. His reaction may suggest the dismay that some Americans felt about women’s fashions. She cannot participate in an activity as mundane as greeting passersby. Some engravings mocked women who attempted to garden in crinolines, while others joked that women in crinolines would blow away like hot-air balloons.[xxix]

Nick-Nax for All Creation, an inexpensive comic monthly, printed a nearly identical version of this illustration a month later.[xxx] Publishers shared engraving plates to keep costs low. Nick-Nax changed the caption to tell a story of a man meeting his betrothed after his long absence.[xxxi] Later that year, the paper published a poem that put the cartoon’s message into words. The lines alerted readers: “For be sure that your dresses the wider they get, The more narrow the mind they disclose.”[xxxii] Such pictures amused Americans throughout the nation. While Nick-Nax for All Creation was printed in New York, responses to puzzles indicated they had readers from Canada, Florida, Santa Fe, and Cape Cod.[xxxiii]

In 1851, Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony donned bloomers to signal their rejection of dominant gender norms.[xxxiv] Stanton contended that “woman is terribly cramped and crippled in her present style of dress.”[xxxv] Some utopian societies in the United States had already adopted pants for women to enhance their ability to contribute, but governments across the country passed laws against cross-dressing in the 1850s.[xxxvi] The outfit implicitly argued that elite white women wanted more than to act as decorative representatives of family wealth. Women could wear trousers and loose-fitting clothes while performing domestic chores, but wearing the outfits in public threatened the men whose needs trousers were designed to meet.[xxxvii] Trousers, still relatively new, symbolized democratic, capitalist progress, and women could not participate equally.[xxxviii]

Bloomers put women’s bodies on public display and challenged feminine values like modesty.[xxxix] The mainstream press dismissed bloomers, and they became a symbol of the reformers’ unwomanly nature.[xl] Nick-Nax for All Creation featured a picture titled The Attractive Points of a Woman’s Rights Lecture, which showed the outline of a woman’s legs, clad in bloomers.[xli] An 1856 article in Frank Leslie’s Ladies’ Gazette called “hideous” bloomers “an outrage” that prompted “a common laugh of derision.” The costume supposedly dated back to the French Revolution, when the “fashion of the male for one month was frequently adopted for the mode of female for the next.” This “extravagance”—the flexibility of the visual signifiers of gender—would culminate in revolution.[xlii] Activists later recalled that opponents associated bloomers with unpopular ideas, such as “free love,” “easy divorce,” “strong-minded[ness],” and “amalgamation” of the races.[xliii] Public disapproval prompted activists to wear dresses again. After just under two years of ridicule, Stanton abandoned the costume in 1853 and convinced others to do the same “for the sake of the cause.” She believed that “physical freedom” was less important than “mental bondage.”[xliv]

Whether in practical bloomers or fashionable crinolines, editors and artists popular mocked women in popular pictures to reflect and reinforce gender norms and American values. Authors, editors, artists, publishers, and printers—often men—controlled visual content. They used images to argue that women should not participate in politics.[xlv] Americans who opposed women’s rights—the majority of the population—bought these sexist images and, implicitly, their ideas about women. Only an elite few activists wrote and read works on the intricacies of political reforms, but these pictures were part of popular conversations.

After enduring ridicule during the antebellum period, women’s rights leaders began to construct their own public image. They came to believe that visual evidence of their femininity, sincerity, and adherence to more familiar conventions of womanhood—at least for the sake of appearances—might attract public support. As female reformers learned that pictures influenced political power, they learned to wage their own war.

Thank you to Alison K. Lange & University of Chicago Press for their permission to print this excerpt,”Lampooning Political Women,” from Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

Keep up with HNY —get the newsletter!

Allison K. Lange is an associate professor of history at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. She received her PhD in history from Brandeis University. Lange’s book, Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement, was published in May 2020 by the University of Chicago Press. The book focuses on the ways that women’s rights activists and their opponents used images to define gender and power during the suffrage movement.

Various institutions have supported her work, including the National Endowment for the Humanities, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Library of Congress. Her writing has appeared in Imprint, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post.

Lange has also worked with the National Women’s History Museum and curated exhibitions for the Boston Public Library’s Leventhal Map Center. For the 2020 centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, she curated exhibitions at the Massachusetts Historical Society and Harvard’s Schlesinger Library.

[i] For a discussion of early nineteenth-century woman’s political activism and women in public, see Allgor, Parlor Politics; Paula Baker, “The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780–1920,” American Historical Review 89, no. 3 (1984): 620–47; Anne M. Boylan, The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Susan Branson, These Fiery Frenchified Dames: Women and Political Culture in Early National Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Lori D. Ginzberg, Women in Antebellum Reform (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2000); Ginzberg, Women and the Work of Benevolence; Lori D. Ginzberg, Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Nancy A. Hewitt, Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822–1872 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984); Isenberg, Sex and Citizenship in Antebellum America; Kelley, Learning to Stand & Speak; Carol Lasser, Antebellum Women: Private, Public, Partisan (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010); Matthews, The Rise of Public Woman; Ryan, Women in Public; Susan Zaeske, Signatures of Citizenship: Petitioning, Antislavery, and Women’s Political Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash.

[ii] Carol Faulkner, Lucretia Mott’s Heresy: Abolition and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Ginzberg, Untidy Origins; Zaeske, Signatures of Citizenship.

[iii] Ellen Carol DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978). For more on the efforts of these early activists, see Alice Stone Blackwell, Lucy Stone: Pioneer of Woman’s Rights (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1930); Faulkner, Lucretia Mott’s Heresy; Andrea Moore Kerr, Lucy Stone Speaking Out for Equality (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992); Kristen Tegtmeier Oertel and Marilyn S. Blackwell, Frontier Feminist: Clarina Howard Nichols and the Politics of Motherhood (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010); Christine L Ridarsky and Mary Margaret Huth, Susan B. Anthony and the Struggle for Equal Rights, 2012; Dorothy Sterling, Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Anti-Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton, 1994).

[iv] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1. Reprint ed. (Salem, NH: Ayer, 1985), 53–62.

[v] Isenberg, Sex and Citizenship in Antebellum America; Zaeske, Signatures of Citizenship; Zagarri, Revolutionary Backlash.

[vi] Lori Ginzberg examines the local conditions surrounding this petition in Ginzberg, Untidy Origins.

[vii] “Petition for Woman’s Rights,” published in William G. Bishop and William H. Attree, Report of the Debates and Proceedings of the Convention for the Revision of the Constitution of the State of New-York, 1846 (Albany, NY: Evening Atlas, 1846), 646.

[viii] Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 174; Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, The History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 4. Reprint ed. (Salem, NH: Ayer, 1985), 73.

[ix] “Resolutions,” Second Worcester Convention, 1851. Reprinted in Stanton, Anthony, and Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, 1:825.

[x] “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,” adopted by the Seneca Falls Convention, July 19–20, 1848.

[xi] Sylvia D. Hoffert, When Hens Crow: The Woman’s Rights Movement in Antebellum America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 127; Isenberg, Sex and Citizenship in Antebellum America, 20–21; Stanton, Anthony, and Gage, History of Woman Suffrage.

[xii] Among the first postconvention images was Leaders of the Woman’s Rights Convention Taking an Airing (New York: James S. Baillie, 1848), Schlesinger Library. Isenberg, Sex and Citizenship in Antebellum America, 44–46.

[xiii] For more on David Claypoole Johnston and his art, see Clarence S. Brigham, “David Claypoole Johnston, the American Cruikshank,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 50 (1940): 98–110; Jennifer A. Greenhill, “David Claypoole Johnston and the Menial Labor of Caricature,” American Art 17, no. 3 (2003): 32–51; Jack Larkin, “What He Did for Love,” Common-Place 13, no. 3 (2013).

[xiv] See, for example, Patent Democratic Republican Steam Shaving Shop (New York: Willis & Probst, 1844), lithograph, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. For more, see Sean Trainor, Groomed for Power: A Cultural Economy of the Male Body in Nineteenth-Century America (PhD diss, Pennsylvania State University, 2015).

[xv] Woman’s Emancipation, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, August 1851, 424.

[xvi] The print was plate 17 in Nagel & Weingärtner’s Humbug’s American Museum Series, published in 1851. Thanks to Lauren Hewes and the American Antiquarian Society staff for research on this series. Signed “AW,” the print was likely completed by Adam Weingärtner himself.

[xvii] See plate from the series called Halloo! Turks in Gotham, which has been digitized by the Library of Congress.

[xviii] Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Greeley & McElrath, 1845), 23.

[xix] Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, 24.

[xx] Frances Willard and Mary Livermore, eds., “Lucy Stone,” in American Women (New York: Mast, Crowell, and Kirkpatrick, 1897), 693–94; Alice Stone Blackwell, “Pioneers of the Woman’s Movement,” Zion’s Herald, August 14, 1918, 1044.

[xxi] Lucy Stone, in Illustrated News, May 28, 1853.

[xxii] Splinters, in Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, March 17, 1855.

[xxiii] T. W. Higginson, “Woman and Her Wishes,” in Series of Women’s Rights Tracts, 26. Sophia Smith Collection Women’s Rights Collection, Box 1, Folder 2.

[xxiv] For more on dress and the ways fashion and vanity undercut women’s status in the eighteenth century (through images and texts), see Kate Haulman, The Politics of Fashion in Eighteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

[xxv] Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016); Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002); Haulman, The Politics of Fashion; Michael Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy: A History of Men’s Dress in the American Republic, 1760–1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[xxvi] Patricia A. Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850–1920: Politics, Health, and Art (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2003), 11–15.

[xxvii] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America, 64.

[xxviii] Gayle Fischer, Pantaloons and Power: A Nineteenth-Century Dress Reform in the United States (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2001), 20.

[xxix] An “Awful Gardener,” in Nick-Nax for All Creation, May 1859, 30; Painful and Sad Warning, in Nick-Nax for All Creation, April 1857, 381.

[xxx] For more on mid-nineteenth-century comic monthlies, see Richard Samuel West, “Collecting Lincoln in Caricature,” Rail Splitter, December 1995, 15–17.

[xxxi] Expedient of the Long-Absent and Just-Returned Algernon Fitzimplies to Shake Hands with Lettice, His Betrothed: With the Hook of His Umbrella Handle around a Lamp-Post, He Is Enabled to Reach across the Hoops, and Take That Darling Hand into His, in Nick-Nax for All Creation, February 1857, 307.

[xxxii] To a Lady, in Nick-Nax for All Creation, December 1857, American Antiquarian Society.

[xxxiii] Nick-Nax for All Creation, January 1860, 272.

[xxxiv] Fischer, Pantaloons and Power, 79.

[xxxv] Letter from Gerrit Smith to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, December 1, 1855, American Antiquarian Society.

[xxxvi] Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 33–37; Fischer, Pantaloons and Power, chap. 2. For more on laws against cross-dressing: Clare Sears, Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

[xxxvii] Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 32–33; Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy.

[xxxviii] See Leora Auslander’s discussion of the sans-culottes during the French Revolution in Auslander, “Making French Republicans: Revolutionary Transformation of the Everyday,” in Cultural Revolutions: The Politics of Everyday Life in Britain, North America and France (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). For more on trousers as symbol of democracy in America, see Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy, 200–201; Hoffert, When Hens Crow, 22–31.

[xxxix] Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 35; Fischer, Pantaloons and Power, chaps. 1–3.

[xl] Some pictures of women in bloomers resembled the fashion plates from Godey’s and Frank Leslie’s Gazette. Examples include Mathias Keller, The New Costume Polka (Philadelphia: Lee & Walker, 1851) and The Bloomer Polka & Schottisch (Baltimore: F. D. Benteen, 1851); Charles Vincent, Bloomer Sett of Waltzes (Philadelphia: Couenfoven & Duffy, 1851); Charles Grobe, The Bloomer Quick Step (Baltimore: F. D. Benteen, 1851); Edward Le Roy, Bloomer, or New Costume Polka (New York: Firth Pond, 1851); William Dressler, The Bloomer Schottisch (New York: William Hall & Son, 1851). The American Antiquarian Society holds examples of these works.

[xli] The Attractive Points of a Woman’s Rights Lecture, in Nick-Nax for All Creation, June 1856, 28.

[xlii] Old Fashion, in Frank Leslie’s Ladies Gazette of Paris, London, and New York Fashions, July 1856, 10. See also Auslander, “Making French Republicans.”

[xliii] Stanton, Anthony, and Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, 1:469.

[xliv] Letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to Lucy Stone, February 16, 1854, as quoted in Fischer, Pantaloons and Power, 103.

[xlv] Although women worked in the publishing and printing industries, they usually performed more menial tasks. Casper, “Introduction,” 10–17.