Historic Hudson Valley (HHV) is redefining what a documentary is with Webby-Award-Winning website People Not Property: Stories of Slavery in the Colonial North. Focusing on the history of enslavement in the Hudson Valley, the exhibition uncovers erased narratives of families and the records that reveal the depth of northern states’ involvement in the slave trade — even after abolition. HNY spoke with Elizabeth L. Bradley, Vice President of Programs and Engagement and Michael A. Lord, Director of Content Development.

Above: C&G Partners, Hand-Drawn Silhouette of Father and Child. Courtesy Historic Hudson Valley.

How does the documentary add to the narrative about slavery in the North?

We wanted to challenge the idea that the North stood apart from the history of American slavery. Until fairly recently, it was common to see Northern slavery as exceptional in relation to Southern slavery. The North was thought to be more enlightened than the South. It never relied on slavery to the extent the South did, and its people came to their moral senses sooner in history. For a long time, the North was depicted as a kind of ‘savior’ region for enslaved African and African-American populations, a land of abolitionists and conductors on the Underground Railroad. People were comfortable with a Gone with the Wind representation of slavery, as essentially a Southern plantation system. In contrast, HHV wanted to show that there was no reasonable distinction you could make between slavery in the North and in the South. At its essence, slavery was the same everywhere. When we started to look at the primary documents at Philipsburg Manor more than twenty years ago, we discovered that the estate operated in much the same way as contemporary plantations in the South; it just happened to be in New York’s Hudson Valley.

What did you discover looking at the documents?

What we discovered was a story of erasure. Slavery’s legacy in New York was hidden, almost invisible. Historians have helped us identify passages in primary documents where the names of enslaved individuals can be found, but had otherwise been erased or discounted from the record — family documents like wills, inventories, correspondence, and census records. To some extent, enslavers purposefully rendered the enslaved invisible. New York abolished chattel slavery (treating people as legal property) in 1799, but even as the statute abrogated enslavers’ property rights, it also called for gradual emancipation of the enslaved — a very long process that allowed enslavement to continue in New York. Authorities, for instance, required that enslaved adults remain under the supervision of their enslavers as indentured laborers, while those who were children at the time the law passed were indentured until their mid-twenties. This kind of thing demonstrates how reluctant New York enslavers were to free enslaved people, and the ease with which they preserved their network following abolition.

What is unique about New York and the Hudson Valley in the history of slavery in the colonial North?

All along the Hudson Valley, enslaving families made their wealth through agrarian trade. Provisioning plantations like Philipsburg Manor would produce raw materials that would be sent downriver to New York City and, from there, to markets around the world, in particular the West Indian sugar plantations of Barbados and Curacao.

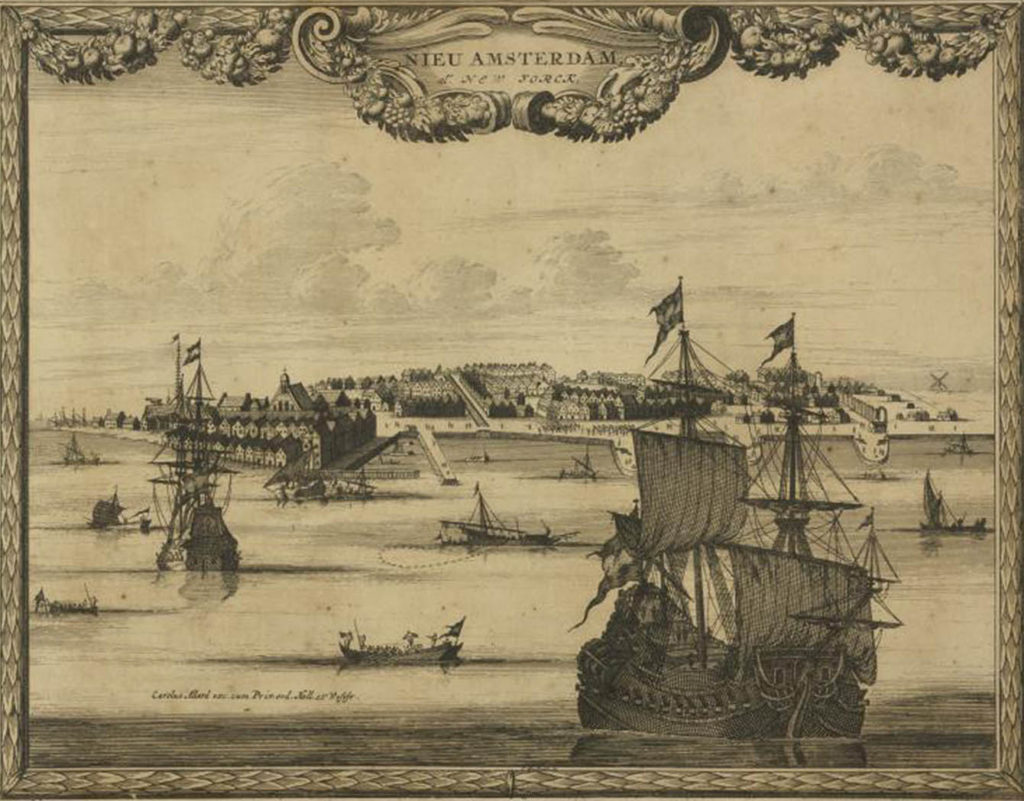

In its earliest years as a Dutch colony, New York’s political economy replicated the Dutch manorial system of patroonship, a semi-feudal arrangement whereby landowners were given large tracts of land in return for settling migrant workers. After 1664 and the advent of English rule, patroonship evolved into a system of large landowners with plantation-sized properties. New York’s system never required as many enslaved laborers as a cotton or rice plantation in South Carolina, but the net effect was the same. As with their southern and West Indian counterparts, the colony’s enslavers operated in a vast and complex economic network that reached virtually every corner of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond. The hub of that system was New York City, which, even by the mid-eighteenth century, was a premier destination, a hub of shipping and trading, even a seat of government for a time. You really can’t talk about slavery in New York without talking about the high seas and the origins of the global economy.

It’s difficult to understand New York City’s place in the global economy without first understanding its role in the Atlantic slave trade. The slave trade was as important to New York’s economic foundations as slave labor, which is saying a lot. Some of the City’s most important institutions were founded by families who derived their wealth directly or indirectly from the slave trade. Those fortunes come down to us partly through those families and partly through institutions. All across New York City, you’ll see family names that are closely associated with colonial-era enslavers. There’s Beekman and Delancey streets in Lower Manhattan, for instance, or Van Cortlandt House in the Bronx. When we think about institutions, universities are a good example. Columbia University, for example, had direct relationships to slavery. The laborers who actually built the university, the students who were admitted, the presidents who oversaw operations — were tied to slavery in one form or another. The same is true of most universities founded in the colonial period, be it Harvard, Yale, Brown, Princeton, or Rutgers.

Another example of a New York institution deeply enmeshed in the history of enslavement is the New York Stock Exchange, on Wall Street. New York City had a slave market at the intersection of Wall and Water streets. That market, which was founded in the early eighteenth century, was a stone’s throw from the city’s emerging financial district, which, by the 1760s, centered on a small coffeehouse at that very intersection — the forerunner of our modern stock market. This was a place where investors, planters, and wealthy New Yorkers bought stock in the cargo of ships coming in and out of port for trade, including chattel slaves. From that point forward, the financing involved in those two markets was closely intertwined. Even after New York State abolished slavery in 1799, New York City remained the financial and banking hub of American slavery. The financial ties were strong enough that, during the Civil War, proslavery city officials floated the idea of seceding from the Union to join the eleven Confederate States of America.

Slavery everywhere and in all epochs was characterized by a tension between the property rights of enslavers and the humanity of the enslaved. “Human property” may seem like an oxymoron to modern readers, and yet chattel slavery is as old as recorded history. How did that tension manifest in your research for the project?

Property in human beings is essentially a legal construct. Outside the context of formal law, it is a fundamentally illogical system that gives rise to precisely the tensions you described. The illogic of the system is wholly apparent to us today, but it supported the enslavers who crafted the laws to meet their own ends.

The story of Joan and John Jackson is illustrative. John Jackson was a freedperson of color who, over a period of forty years in the early eighteenth century, fought to keep his family together despite the many legal injustices imposed upon them. He married a young enslaved woman named Joan and eventually sued in court for Joan’s freedom. John won, and together, he and Joan started a family that, at one point, included at least seven children. But Joan’s former owners disputed her legal status as a free woman, arguing that she had never actually been freed. Tragically, the courts agreed, and Joan suddenly found herself reenslaved. That, in turn, forced an even greater dilemma: if Joan had never been emancipated, then what was the legal status of her children, who until this point had been considered freeborn?

According to colonial slave law, the mother’s legal status determined that of the child at birth. If Joan Jackson was enslaved at the time she gave birth to her children, the children ought to have been enslaved as well. In the end, a court found that Joan’s former owners had not manumitted Joan and that her children were indeed slaves, not freepersons. All of her children were therefore reenslaved, divided up as “property” among several of the region’s enslaving families.

John eventually secured freedom for five of their seven children, but only after Joan had passed away. It’s a devastating story that illuminates the tension between property and humanity in the lived experiences of the enslaved. Harrowing though it is, John and Joan Jackson’s story is also inspiring in its demonstration of the tenacity of the human spirit, the will to keep kith and kin together, against the odds.

What methods did you use to recover and convey the humanity of the enslaved?

When the project began about five years ago, we discussed how best to frame our material and recover this history. We wanted to facilitate a visitor experience in which people could choose their own pathways, getting a clear picture of what life was like for the enslaved. A rigid chronology would have clashed with the “user-choice” spirit of an interactive documentary, so we went with a more thematic approach. We divided the narrative into four “chapters” that are loosely chronological. The first chapter, “Defining Slavery,” is a kind of overview of the documentary, whereas the second chapter, “Being Enslaved,” is about the lived experiences of the enslaved, with stories about labor, marriage, family, and community. The third chapter is called “Choosing Resistance” and focuses on a variety of resistance strategies and their consequences. The fourth chapter, “Pursuing Justice,” is about the complicated process of Northern emancipation and the legacy of denial and misremembering that followed.

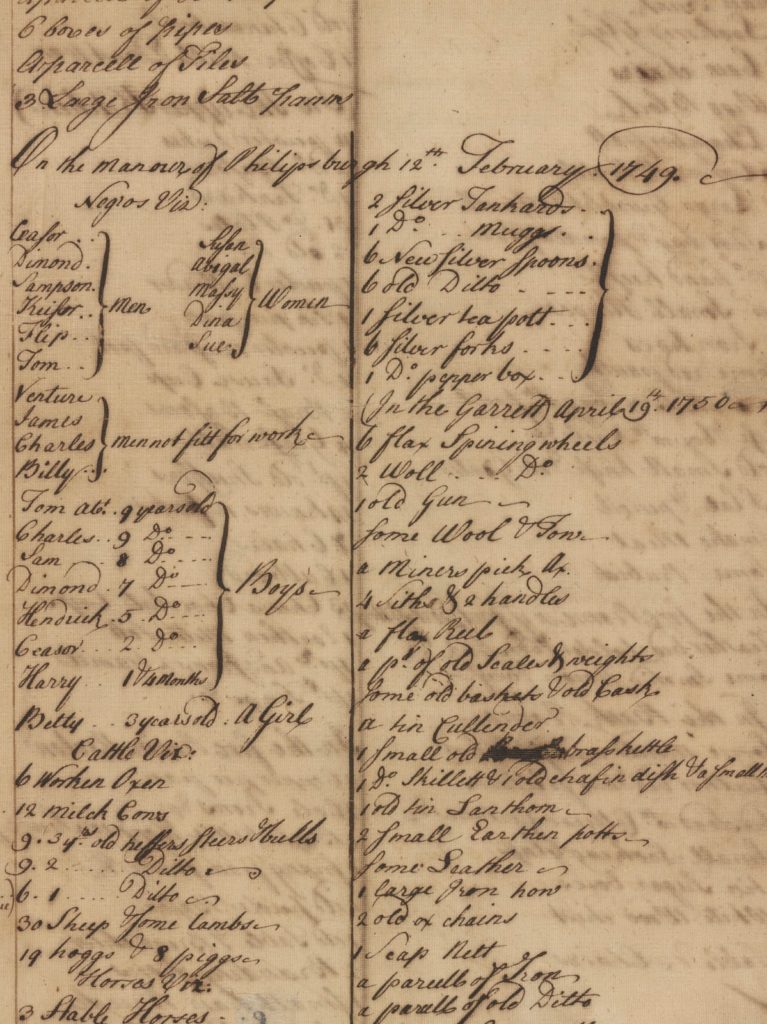

The interactive primary documents on our site give users the chance to do the interpretive work of historians. We have inventories, bills of sale, and advertisements for runaway slaves from Philipsburg Manor, all of which feature enslaved individuals as commodified subjects. The interactive documents encourage people to read these materials from the point of view of the subject rather than the enslaver who wrote it. You need to read between the lines in order to render and begin to understand the enslaved experience.

The Philipsburg Manor inventory, for example, is a legal docket written in script, listing all of the property belonging to patriarch Adolph Phillips at the time of his death. At the top of the list, just above the figures for cattle, livestock, silverware, linens, and other chattel property on the estate, are the names twenty-three men, women, and children. Visitors to the site can click on those names and get their backstories. Following their enslaver’s death in 1750, this community of twenty-three people was torn apart over the course of five to six months. Family members were sold to different owners. An eight-year-old boy named Sam was sold at auction, by himself, apart from his loved ones. Despite its banal appearance as a financial ledger, the Philips inventory does illuminate the experience of being classified as property, the way a person could be bought and sought multiple times over the course of her life. That hits home for many of our users, who begin to understand that the names on the list are individuals with their own unique stories. That is the essence of our project, the reason we called it “People Not Property.”

It was challenging to meaningfully depict and dramatize the stories for which we had enough information, to bring to life the stories of the enslaved in a manner that was sensitive and appropriate. We knew from live events at our historic properties that third-person reenactments are very effective in creating an immersive environment. The question became, simply, how we could do reenactments in the context of a video? Digital content is hugely attractive to audiences, but it can also be quite tone deaf, so we had to work very hard to strike the right balance of content and digital presentation. We hit upon two different approaches. The first is a wordless reenactment, interpreted by a narrator, in which interpreters dressed in eighteenth-century clothes demonstrate activities that the enslaved would have undertaken: churning butter, operating a water-powered grist mill, working in the garden, or thrashing wheat and rye. The second approach is the reading of a primary document that explains the story you’re seeing.

Both methods help viewers understand the kind of work done by the enslaved, the conditions under which they lived, and the sense of powerlessness that came with a lack of self-ownership. We don’t ask visitors to imagine that the interpreter in front of them is enslaved, but we do ask them to conjure the full spectrum of human experience at Philipsburg Manor.

How did partnerships shape the making of the documentary?

We’ve exchanged ideas with a number of historic homes and other institutions in the Northeast, including Cliveden, Pennsbury Manor, Stenton, the Penn Home, and Joseph Lloyd Manor on Long Island. All of us are engaged in the same work and yet come from different places, with distinct ambitions and strategies. What we didn’t anticipate was that we would take on a kind of mentoring role for the group. This past February we convened the first meeting of a regional consortium of local historical institutions, encompassing the region from Greenwich and Long Island up to Albany. It was a cathartic experience for many of the attendees, who may at times feel as if they’re the only institution in their neighborhood doing this kind of work. You sometimes hear the terrible comments people make when they visit a southern plantation and hear about slavery instead of the idyllic Scarlett O’Hara story. We wanted to hear from our colleagues in the North, What have you heard? What particular challenges do you face? How are you coping with them? It was a really rewarding session. There’s a lot we can learn from each other, a lot of resources we can share. So this was just the first step, and we’re looking forward to doing it again soon.

And…congratulations on winning a Webby!

We’re thrilled that the Webby Awards have recognized People Not Property: Stories of Slavery in the Colonial North with the 2020 award for Best Website in the Education category. This honor allows us to expand the reach of our work on the lives of enslaved colonists, and helps us in our efforts to share their moving personal histories with as wide an audience as we possibly can.

Click here to experience the People Not Property Documentary.

Historic Hudson Valley is a not-for-profit education organization that interprets and promotes historic landmarks of national significance in the Hudson Valley for the benefit and enjoyment of the public. The mission of Historic Hudson Valley is to celebrate the history, architecture, landscape, and culture of the Hudson Valley, advancing its importance and thereby assuring its preservation.

Interviewed by Joseph Murphy, HNY Grants Associate

Keep up with HNY —get the newsletter!

ELIZABETH L. BRADLEY is Vice President of Programs and Engagement at Historic Hudson Valley, where she leads a team that interprets Northern slavery and regional storytelling, among other subjects. She is the author of Knickerbocker: The Myth Behind New York and New York (Cityscopes) and the editor of the Penguin Classic Editions of A History of New York and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Other Stories, both by Washington Irving. She is a Fellow of the New York Academy of History.

MICHAEL A. LORD is Director of Content Development at Historic Hudson Valley. He is a public historian with over twenty-five years of experience in program development, interpretive planning, museum education, and historic site management. A graduate of Amherst College with degrees in History and Black Studies, Michael began his career in public history working in the African American Programs department at Colonial Williamsburg. Michael’s first task at Historic Hudson Valley was to develop a new interpretation for Philipsburg Manor, introducing visitors to the story of enslavement in colonial New York. More recently, Michael has co-produced the Webby-award winning interactive documentary called People Not Property: Stories of Slavery in the Colonial North, and Runaway Art, an art and social studies school curriculum that uses local colonial runaway advertisements. Michael has also written and produced numerous online blog posts, videos, and museum theatre presentations.