How do we preserve a sense of place when its context is constantly changing? We continue our Stonewall 50 blog series by discussing the importance of preserving place-based LBGTQ history. HNY interviewed Ken Lustbader, one of the Project Directors of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, who discusses how digital preservation can be an effective tool for passing stories intergenerationally, particularly when some of the most important historical spaces were illegal, transient, or have since been renovated.

Don’t miss the rest of the series, join our newsletter.

HNY: Let’s start with Stonewall. Stonewall has arguably become as much a symbol as a brick-and-mortar institution in the popular imagination. Yet it is a concrete place and arguably the centerpiece of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. What is the importance of place to LGBT history and to the LGBT rights movement today?

KL: We’re using the Stonewall Inn and other places to demonstrate that LGBT history is all around New York City, and that LGBT history is American history. Three historic preservationists started the project, and our team now includes an employee who is also a preservationist. As place-based historians, we look at sites and try to embed histories into them, creating visceral connections and narratives that people to see, physically touch, and experience, making a concrete connection to history. People go to places like the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building, or Mount Vernon and Mount Rushmore, because those sites speak to a cultural current, a historic moment, a regional or national identity. It’s really important that LGBT history is considered in the same terms: people can go to Stonewall and have a visceral experience at this location of a key turning point in the LGBT rights movement. People read history in books or listen to history podcasts, and share historic narratives from one generation to the next. Places, by contrast, have a different cognitive connection for people, allowing them to travel in time at a specific location. That’s what’s so effective about, say, Gettysburg or other Civil War battlefields. In a similar sense, people come to Stonewall to experience the building and streets where the uprising took place.

“In 1969, Stonewall was mafia-run. It was pathetic on the inside, painted black, with no running water; it served watered-down drinks and was constantly under threat of police raids. But it was the only game in town!”

It’s important that we view Stonewall in light of its historic associations. The bar’s history reflects the shift from oppression to liberation and eventual memorialization. Bars were central to LGBT identification. They were the primary spaces where people could meet, mingle, make connections, have a sense of community and develop an identity. They were also the launching point for job opportunities and politicization, through connections and conversations. From the 1930s through the late 1970s, LGBT bars were mainly run by the mafia due to the discriminatory policies of the New York State Liquor Authority. In 1969, Stonewall was mafia-run. It was pathetic on the inside, painted black, with no running water; it served watered-down drinks and was constantly under threat of police raids. But it was the only game in town! It had a big dance floor and played popular music. The 1969 uprising came in response to a routine raid. What happened over six days and nights was a cat-and-mouse game of resistance in the streets of Greenwich Village.

Today, people can walk around and get a sense of why Christopher Park [situated across from the Stonewall Inn] and Christopher Street directly in front of Stonewall are such important symbols for memorializing this history. It also creates a space of reflection for tragedies like the 2016 Pulse Nightclub shooting, or celebrations like Pride Month.

HNY: How does the Stonewall rebellion influence our understanding of LGBT life in New York City before 1969? How do those earlier sites complicate the Stonewall-centered narrative?

KL: LGBT history is a relatively new inquiry dating from the 1970s. The study of LGBT placed-based history is an even more recent inquiry dating from the 1990s. It’s a new field that is really important to understand. We’re looking at places beyond the Stonewall Inn, that reflect the community’s political and oppositional issues and discrimination. Bars like Stonewall embody that in many cases. But beyond them, we’re looking at sites that convey the community’s influence on American culture. It might be a performance venue, such as the Winter Garden Theater, where West Side Story–a collaboration of a gay man, a lesbian, and some bisexual men–premiered. It could be the residences of notable individuals, places where important literature or architectural works were produced. By looking at NYC through an LGBT lens, we’re illuminating the rich history of LGBT New Yorkers before Stonewall, from the nineteenth century to today. There’s an erasure of this history, and we’re trying to recover that history and make it visible in a concrete way, using extant buildings throughout the city to change people’s perceptions. That history is at your fingertips through our recently launched app as you’re walking down the streets.

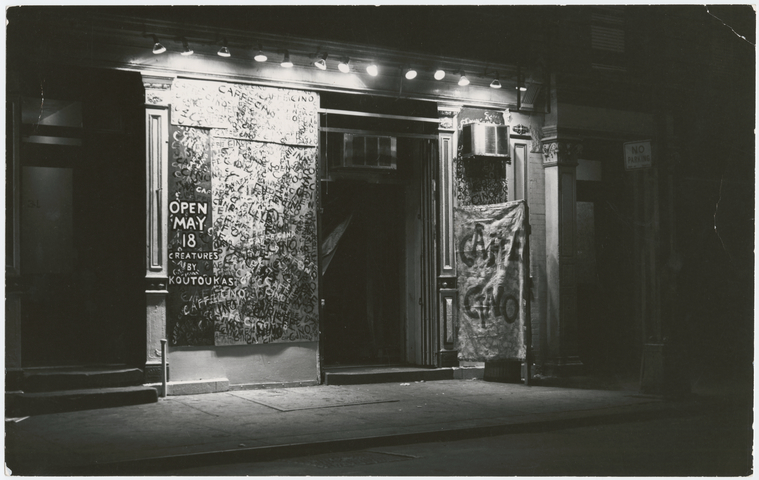

There is also this sense of before Stonewall and after Stonewall. Most people think gay history starts after Stonewall, and we really try to dispel that myth. There was a rich cultural life and political activism in NYC pre-Stonewall, especially with the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, two “homophile” organizations that were effective in advancing LGBT issues in the 1950s and 60s. We like to identify sites that reflect the community’s influence throughout this city and yet were shaped by LGBT oppression and discrimination. Take Caffe Cino, the birthplace of Off-Off Broadway theater. In the decade from 1958 to 1968, Caffe Cino was an incubator space for gay playwrights and actors. It was also an alternative to the bars as a meeting place. Or consider the community centers where LGBT people appropriated the space to discuss oppression and discrimination. We’re trying to recover all the myriad ways LGBT people lived their lives pre-Stonewall.

The impact of Stonewall is profound: it did change the trajectory. Immediately after Stonewall, there were new groups forming in NYC like the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. Many of their members were already activists in some way or another, either with the Mattachine Society or Daughters of Bilitis, or were involved in the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, the hippie and yippie and other anti-war movements. So people were already activated in some way and were raising consciousness about broader issues in the 1960s. Stonewall became the armature that allowed those people to react and say, “It’s our turn now! We’re going to take advantage of this moment!” Stonewall may not have been the birth of the modern gay rights movement, but it was a crucial turning point–the moment that people became more visible and vocal about LGBT rights and began protesting and organizing in a very direct way.

What is remarkable is that the advance of LGBT rights has sometimes outpaced historical documentation of the movement. [Laughter]. Writing our history has taken a backseat, so to speak, to wonderful advances in employment opportunities, marriage equality, and visibility–all happening intertwined with the AIDS epidemic. But it’s so important to know one’s past and understand the battles, struggles, bravery, and personal losses of the activists who came before us. In the 1960s, if you were a gay man or a lesbian, or a gender-nonconforming person, and you found yourself in a bar, you could at any moment be arrested, lose your job, lose access to your family, your religion, and the whole trajectory of your life would be forever changed.

Without knowledge of past activism, there is the danger of history repeating itself. Younger activists today need to know that history, especially the movement’s development over time. An example are the street theater tactics and “zaps” that AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) modeled from the earlier Gay Activists Alliance(GAA). GAA was probably the most important LGBT activist group operating in the 1970s. Its primary innovation were “zaps”, which were public disruptions targeting public figures that were quite effective in calling attention to discrimination against gay people. ACT UP adapted the zaps to a new context shortly after it was formed in 1987, drawing attention to the AIDS epidemic. What we’re doing is using buildings, actual brick-and-mortar locations, to tell those stories.

HNY: Stonewall is a touchstone even internationally. But what are some of the legacies of Stonewall right here in New York City?

KL: The immediate legacy of Stonewall is its role in the expansion of activism and quest for liberation here in New York. Stonewall was an uprising that took place over six nights in June 1969. The main reason it was so effective was that activists were already in place who understood that this was an important moment to seize on. Because of its concentration of activists and LGBT people, NYC was an incubator space that fed off the energy and power and diversity of its people. There were a diverse range of individuals, including people like Craig Rodwell, Martha Shelly, Slyvia Rivera, and Marsha P. Johnson, who, contributed to a collective energy and idealism helped promote this huge groundswell of activism.

In fact Rivera and Johnson formed an activist group called STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), which was especially ahead of its time. Talk about discrimination within the community: they were completely cast aside and looked down on because of their gender-nonconforming presentation while other parts of the movement wished to normalize, secure employment opportunities and equal rights and things like that.

After Stonewall, with this rise of radical activists, the older East Coast homophile leagues agreed that the following year they’d gather in NYC to commemorate Stonewall with a march. The “Christopher Street Day March” took place on the last Sunday in June of 1970. That first march has transformed into what it is, the current pride parade. It was shrewd branding, seized on by people who had the foresight and organizational abilities to think, “Now’s the time to do it!” The commemoration was based in New York City, but they coordinated with activists across the country. It was a collective effort of disparate individuals, all with the same cause.

“If you removed all of the homosexuals and homosexual influence from what is generally regarded as American culture you would be pretty much left with ‘Let’s Make a Deal.'”

HNY: The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project app reaches audiences well beyond New York City, particularly LGBT youth. Why is it important to connect LGBT youth to this history?

KL: Gay people are everywhere, but their stories aren’t passed-down in an intergenerational sense, through family members or through religious affiliations or other traditional oral histories. That poses a distinct challenge. Earlier generations grew up knowing well the force of anti-gay rhetoric and the lack of attention paid to the AIDS epidemic. Nowadays, a younger, post-Will & Grace generation has been fortunate to grow up with visibility, opportunities, more integrated gay lives. For many, the closet is not a central theme, or at least it’s not a very large closet.

There’s a great quote from Fran Lebowitz that I think neatly summarizes the LGBT community’s contribution to the humanities: “If you take out all the homosexuality from American culture, you’d be left with the old television game show ‘Let’s Make A Deal.’”[Laughter].

HNY: How does the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project reflect the diversity of LBTQ history in New York City?

KL: Quite frankly, it’s a challenge. We try to identify sites that reflect the full diversity of the community, in race, class, creed, gender identity and geography. But the nature of LGBT research is inherently challenging. We’re a bottom-up research project. Many of our sites are commercial establishments; others are associated with individuals with limited documentation. Yet there are so many sites that are not reflected in our project, either because there are no written records or because people claimed space in the most transient way possible. For instance, trans people could take over the back of a restaurant for a dinner hour. Women of color, who couldn’t afford to open their own bars, or weren’t welcome at majority-white bars, went to people’s houses and had potluck suppers–it’s hard to identify and research these important narratives that aren’t often recognized.

The flip side is that we’ve documented spaces that we’re hoping touch on diversity in the community. Take, for instance, the Mount Morris Baths in Harlem, which opened in the early 20th century as a traditional bathhouse but was appropriated as a gay male bathhouse and later re-appropriated by men of color, who were often excluded from other bathhouses. There are so many other locations that convey the full array of sites in the LGBT community of people of color: Lorraine Hansberry’s apartment on Bleecker Street; Langston Hughes’s home in Harlem; or the recently-demolished Paradise Garage, which was instrumental in the making of garage music.

What we do know and talk about is the very real discrimination that took place within the LGBT community. For example, the Bagatelle, a lesbian bar in the Village with a clientele of mostly middle-class white women, was not very welcoming of people of color. Audre Lorde writes about going there with white friends and being the only one carded.

HNY: Sites listed on the app include homes, cemeteries, and beaches. What insights can such locations offer about the balance of personal and political motivations for New York City’s LGBT community?

KL: Yes. A great example is the Continental Baths in the basement of Ansonia Hotel in Manhattan. It opened in 1968, just before Stonewall, as a clean and lavish bath house catering primarily to white gay men. But it was also a place where socializing and political discussion took place, a little of everything. I spoke once with Dick Liesch, the late president of the Mattachine Society, who said, “Oh, yeah, we would sit in our towels and chat with each other. That’s where we had some of our best political discussions ever!” So in that case the personal was certainly political. Also, beaches have historically served as cruising grounds and socializing places. Jacob Riis Beach in Queens – or “Screech Beach,” as it came to be known, that was accessible by public transportation – was so popular among LGBT groups by the early 1970s that the Gay Activists Alliance set up tables there to raise people’s political awareness. These types of social spaces provide opportunities for people to come together and be informed about politics.

We include cemeteries because it’s an interesting tool to convey LGBT history by recognizing the final resting places of LGBT individuals from the 19th and 20th centuries. We recently did tours at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx and Green Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. It’s incredibly informative and meaningful to visit the grave sites of, for example, Emma Stebbins, the nineteenth-century sculptor of the “Angel of the Waters” statue at Central Park’s Bethesda Terrace, who was in a same-sex relationship with Charlotte Cushman, a leading actress of the day. Or the graves of Emery Hetrick and Damien Martin, who together who founded wehat is today named the Hetrick-Martin Institute in Manhattan [the nation’s largest LGBT youth services organization], more commonly known as the Harvey Milk High School. We visit the gravesites of a range of composers, from the sublime — Leonard Bernstein – to the most popular – Paul Jabara, author of “It’s Raining Men,” one of the most iconic gay songs of all time.

HNY: How are the Stonewall 50 commemorations being received?

KL: I’m thrilled to see people’s interest in the LGBT history and how it connects to the Stonewall Uprising and that earlier history of LGBT life in NYC. I’m excited to see people in search of a personal connection to stories about Stonewall 50. I get great satisfaction from this, whether I’m doing a presentation for middle and high school school students or leading a walking tour of sites on the Upper West Side. It’s wonderful to see people’s eyes open wide, knowing that they’re walking amidst a history they didn’t really know beforehand. I get to see people realize in real time that they’re part of this broad trajectory of humanity and activism that relates to both their own identity and LGBT visibility and rights today. And that it wasn’t a ‘walk in the park’ to get here: so many people’s lives were sacrificed and hurt because of discrimination. With Stonewall 50, it’s an opportunity to engender an appreciation of history, not just for this year or month, but for the future as well.

The LGBT Sites Project was supported in part by an HNY Action Grant. Learn more and download the app at www.nyclgbtsites.org.

Interview by Joseph Murphy, Interim Grants Associate.

Ken Lustbader is a historic preservation consultant based in New York City. Between 2007 and 2015, he served as Historic Preservation Program Director at the J.M. Kaplan Fund where he was responsible for developing and implementing US and international grant initiatives. Prior to that he was lead consultant for the Lower Manhattan Emergency Preservation Fund, a coalition of five preservation organizations that was formed in response to the September 11 attacks. In that capacity he developed and implemented a comprehensive preservation strategy that included the conservation of in situ elements of the World Trade Center that are now integral components of the National 9/11 Memorial Museum. Between 1994 and 2002, he was the Director of the New York Landmarks Conservancy’s Sacred Sites Program.