Preservation Long Island (PLI) is embracing its role as keeper of a historic house museum of Black enslavement by engaging in public discourse around present-day issues. Centering the life history of Jupiter Hammon, the first published African American author, PLI will recruit experts to plan public-facing programs that explore the consequences of enslavement on Long Island. PLI received a Vision Grant in preparation for the “Round Table” series, which will provide opportunities to discuss and frame a multi-year reinterpretation initiative and to learn about the historical figure who inspires it all. HNY spoke to Lauren Brincat, Curator, and Darren St. George, Education and Public Programs Director.

HNY: What about this house museum makes it significant to Long Island?

Lauren: It’s a significant site for its connection to the American Revolution. It’s one of the great manorial patents (land grants) that carved settlement on Long Island during the Colonial Period, which has influenced the social and municipal structure of Long Island today.

It’s a site of Black enslavement, too. And that’s really important, as slavery was the engine that built American economic prosperity.

Lauren: And what’s most significant about this place is Jupiter Hammon, who composed his most well-known works while enslaved at the house. As one of the founders of American literature, Jupiter is a nationally significant historical figure.

HNY: In the Lloyd family estate, who was Jupiter Hammon?

Lauren: He was born into slavery at the Henry Lloyd house in 1711. Jupiter Hammon would live on to become the first published African American writer.

Darren: Hammon’s accomplishments are discussed nationally, if not internationally. It’s remarkable to have a blueprint; to have first-person narrative of his feelings, documenting an enslaved life during this time.

Lauren: After the death of Henry Lloyd II, the property is divided among [Henry’s] four sons; Joseph, John, Henry and James. James and Henry are loyalists, and Joseph and John are in favor of American independence.

The property is later occupied by the British army, causing Jupiter to flee to Connecticut with Joseph. American defeat at the Battle of Charleston results in Joseph taking his own life. [Hammon] is then inherited by Joseph’s nephew John.

Darren: It’s interesting to think that in 1776, as he is writing, Americans were fighting for what we called freedom. To be able to dictate who we want to represent us.

Lauren: Hammon’s first published work in 1760 is written at the Henry Lloyd house, and it’s called “An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penetential Cries.” He writes a lot in Connecticut, and it’s not until after 1782, after the war, that he returns to Long Island, to the Joseph Lloyd Manor. Being “pro independence” ultimately results in many families becoming refugees, in a sense.

And so, you have this divided family because of the American Revolution. Interestingly enough, Jupiter Hammon was not in favor of the war. Twice he would have to flee invading British forces and experienced firsthand the death and destruction the war had caused.

Darren: Also, it’s surprising to think of Long Island as one of the largest enslaved populations in North America during the 17th and 18th centuries. Collectively we remember enslavement in the South, not so much the North; however there was plenty of enslavement in the northern states.

In particular, on Long Island. We have ports up and down the entire shore: it’s commerce, it’s profitability and, unfortunately, it’s greed.

Lauren: Looking at our Long Island communities and how they are structured today, with some of the most segregated suburbs in the entire country, you can trace that back to the 18th century, back to this moment in time.

Lauren: We have a multi-generational story. We can talk about that part of American history and globalism—and the dehumanizing institution of slavery that built up this country and the colonization of America—with our site, the Joseph Lloyd Manor.

HNY: How does Jupiter Hammon become literate? What does it say about his relationship with the Lloyd family? Does this shape his understanding of enslavement as an institution?

Lauren: Only five years older than Joseph, Jupiter is similar age as all four Lloyd sons. There’s a schoolhouse on the property, which could mean they were educated together.

Darren: It’s a social truism (norm) that one could not educate enslaved men, women or children. But it was common practice, actually, for African Americans to be taught to read and write.

Lauren: Although there were many laws throughout the 17th and 18th century that restricted the agency of enslaved people, there were no laws in New York that made it illegal to teach a Black person, freed or enslaved, to read or write. And because he was a gifted reader and writer, it’s thought that Jupiter Hammon tutored Joseph and other members of the household. There’s also some thought that he performed duties of a clerk for the merchant business of the Lloyd family.

Darren: He has a rather long life and starts to live into the world of emancipation. A lot of his writing starts to question whether or not this is a good thing. Much of his writing encouraged reluctancy to other enslaved men and women, to not rush to be manumitted (released from slavery). He felt it may not be the right action for all; depending on their status in life, what they did for a living, or how they could sustain themselves if they were to be granted freedom.

Lauren: When Hammon is writing, he talks about what would happen if enslaved people were to be freed. And he thinks about what that would look like. He believed, as an enslaved person in his eighties, that freedom wasn’t for him. So, he has been thought to be this apologist for slavery. What’s tricky about Jupiter is that he has difficulty reconciling his religious beliefs with knowing that “slavery is a sin.” He is deeply religious, he is an evangelizer. And growing up with the Lloyd family, he has a difficult time seeing them as sinners. And I think that is why he hasn’t been celebrated. He’s been thought of as not saying what we would hope an enslaved person would say about enslavement. There are preconceptions that have unfairly characterized Jupiter Hammon, yet there’s a lot more nuance that we have to pick out, to put ourselves in his shoes, to understand his perspective and his time period.

Darren: So, his poetry is really challenging to unpack. Thankfully, Hammon was well-educated and talented.

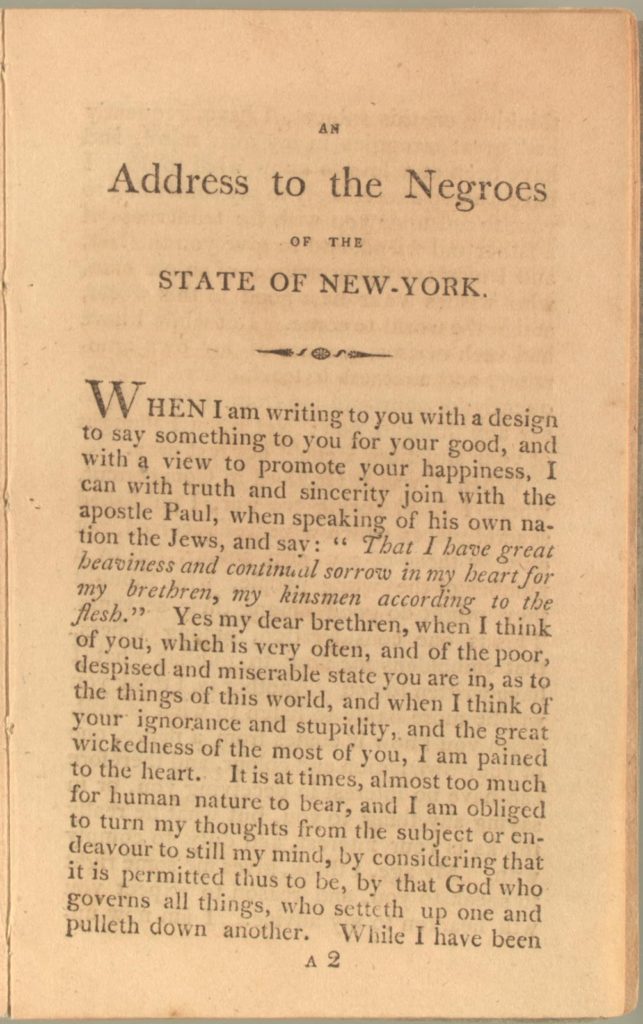

Lauren: His most well-known work, “Address To The Negros In The State of New York,” also known as “The Hammon Address,” was written at our house. And he was invited to the first recorded meeting at the African Society of New York, which is where it is believed he delivered that address in 1787. It is also believed that the Lloyds prevented him from publishing the more recently discovered work, his Essay on Slavery, because of the views that he expresses in it. It is his most direct critique of the institution of slavery. He is enslaved by three generations of the Lloyd family and dies in his nineties. And during his lifetime he produced seven published works, and recently two other works that were not published have been discovered. In total, what we know of are six poems and three essays.

On Jupiter Hammon’s birthday, Saturday, October 17, community members will be able to join us as we designate the Joseph Lloyd Manor as a Literary Landmark in his honor.

Lauren: And that’s something we really want to get at with the Jupiter Hammon Project, too. His literacy gives us insight into his self-expression, his identity and his voice, helping us to really understand his values.

HNY: Can you tell us about the making of this initiative?

Lauren: There are a number of institutions on Long Island that are actively thinking about how they can best interpret the lives of the enslaved people who lived at their properties. We at PLI think it’s important that when visitors come to our houses, they are receiving a rigorous and relevant experience, that’s responsibly equitable as well. From the beginning, we assembled community advisors and people who are engaged in the interpretation of African American history on Long Island, and invited them to help shape how we’re going to proceed with the reinterpretation of our site. We feel there is an opportunity for us, as a new staff who are excited to do new things, to think about expanding the narrative that gives equal weight to the multiple perspectives and individuals who have shaped the houses throughout their multi-century histories. The Joseph Lloyd Manor is the logical place to start, in that it’s significant because of Jupiter Hammon.

HNY: How did PLI come to use their Vision Grant?

Darren: The Arc of Dialogue training really challenged the PLI staff, board members, and council, to learn how to converse in a productive manner. How do we ask the right questions; how do we encourage those insightful, meaningful answers? How to engage in dialogic ways with individuals?

Lauren: That training was really amazing. We convened our staff, members of our Jupiter Hammon advisory council, a couple of trustees from Preservation Long Island, and Sarah Pharaon from the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience.

Darren: Sarah started off the session talking about the dialogic conversation. What is the goal of that; what do you want people to do after they visit your house?

Lauren: One thing that Sarah [Pharaon] talked to us about: these different truths. Forensic Truth, for example, is the space in which we live as a history organization. It’s the facts. And I think there is this feeling that, as an organization, as people who work as historians, [that we] need to teach people, we need to tell them lots of facts; But what we really need to do is engage people in dialogue.

Darren: It really is insightful, how the Coalition approaches conversations between others: Before you begin a conversation with another, what should you be thinking about? How do you recognize another individual and what they’re bringing to the table, before the discussion begins?

HNY: What’s next for the Jupiter Hammon Project in 2020?

Lauren: What we want to do with the multi-year initiative is to consider the lives of the enslaved on their own terms. To reflect their agency and their humanity as a people, who are surviving and making lives for themselves within the very strict structure of enslavement.

Darren: The stories are not about enslavement. They are about people. They are about men, women, and families. And how do you share those stories in a respectful and meaningful manner? That’s what we’re hoping to do with the Jupiter Hammon Project. How can we better serve the community and their needs, and the stories they want to hear and the stories that resonate with them?

That’s how we came up with the Jupiter Hammon Project: A series of three public-facing round tables, with expert panelists and community members who could talk and conduct a discourse in a productive and respectful manner. The project isn’t just about reinterpretation.

Lauren: We’ll have Joe McGill from the Slave Dwelling Project, who will be one of our panelists. And other folks who are in the museum field, actively engaged in interpreting difficult histories, and specifically histories of enslavement.

Every round table discussion will be moderated by Cordell Reaves, from NYS Parks and Historic Sites. And it will be interactive, with breakout sessions in which participants can engage with community stakeholders to identify themes and ideas our communities and scholars want to explore.

HNY: What kind of topics could come up in the Round Table Series?

Lauren: We’ll be focusing the first Round Table on global commerce, the manorial system, the Manor of Queens Village (today all of Lloyd Neck) within the Black Atlantic, and slavery on Long Island. And then the second really focuses on the voice of Jupiter Hammon, on his poetry—getting into his identity and self-expression. Then the last one, the third round table, will focus on how to implement these lessons and ideas that our communities and scholars have deemed are important to explore.

Click here to learn more about the Jupiter Hammon Project 2020 and to participate in the Jupiter Hammon Project Roundtable events.

Preservation Long Island is a 501c3 non-profit organization committed to working with community members on Long Island “to protect, preserve, and celebrate our cultural heritage through advocacy, education, and the stewardship of historic sites and collections.”

Interviewed by Kordell K. Hammond, HNY Grants Assistant

Keep up with HNY — get the newsletter!

Lauren Brincat is the curator of Preservation Long Island where she oversees a collection of over 3,000 objects, 185 cubic feet of archival materials, and three historic houses. Lauren has worked in museums and historical societies for over a decade, specializing in curation, exhibition and program development, and collections management. She has held positions at the Museum of the City of New York and the New-York Historical Society, where she co-curated the redesigned Luce Center for the Study of American Culture. Lauren holds a B.A. in History and Anthropology from the College of William and Mary and an M.A. in American Material Culture with a certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Delaware.

Darren St. George has worked at historic properties across Long Island, where he has unitized his BS in Psychology and BA in Communications & Media Studies from Fordham University to develop unique educational programs for diverse audiences. For almost ten years, he served as the chairman of the theatrical & fine arts department in West Islip and continues to foster productive and powerful educational experiences.