By Lee Bernstein

The New York History Journal has been re-imagined and re-launched by our partners at the New York State Museum and Cornell University Press. The journal welcomes submissions from public historians, municipal historians, museum professionals, and archivists, in addition to academic historians–very much in the spirit of Humanities New York as we help build the burgeoning field of the public humanities. The article we’d like to share with you on the blog concerns “The Sing Sing Revolt” which, coming ten years after the uprising at Attica, is less talked about, but sheds important light on the way that event shaped the criminal justice system in New York.

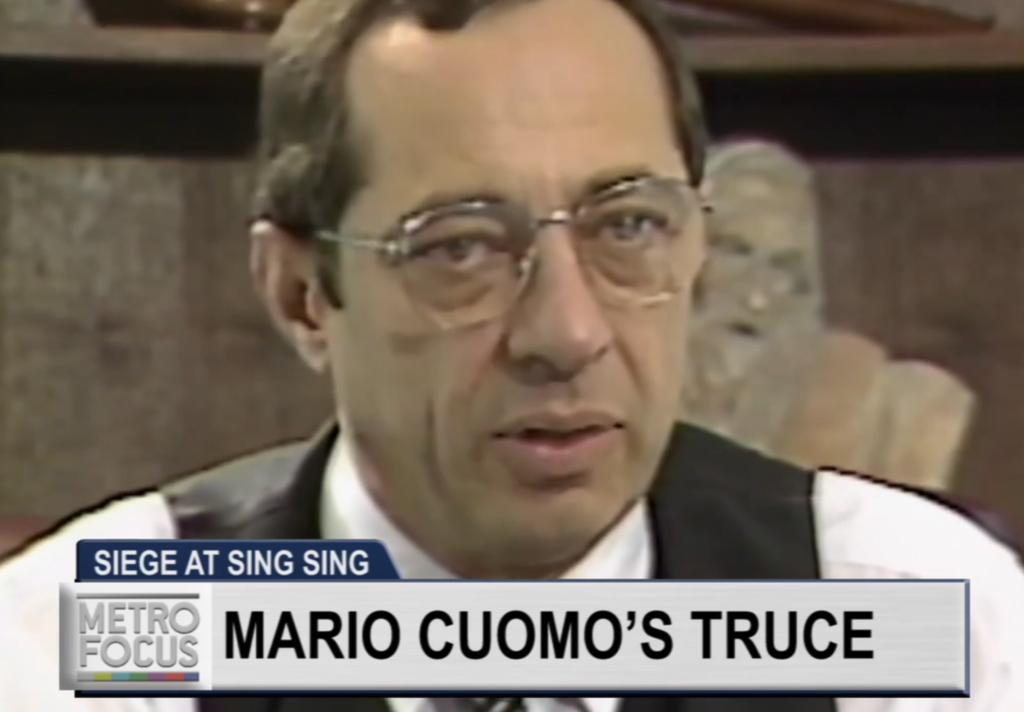

As 1983 began, New York’s prisons reached a chokepoint: in the past decade the inmate population went from 12,444 to 27,943. Mario Cuomo, who would become the nation’s most prominent liberal politician after delivering the keynote address at the 1984 Democratic National Convention, prepared to take the oath of office to become the state’s fifty-second governor.(1) Corrections officials scrambled to find beds for four hundred new people each week in crumbling facilities and repurposed public buildings. This overcrowding occurred, to different degrees, throughout the system—city and county jails, juvenile facilities, and in state-run facilities variously classified minimum, medium, and maximum security. Multiple factors converged to create this overcrowding, including the war on drugs, the victims’ rights movement, and new “truth in sentencing” laws.(2) In addition, declining tax revenues and the economic struggles of the state’s voters limited the state’s ability to fund new prison construction and to accommodate the educational, therapeutic, and social needs of its burgeoning prison population. Access to basic needs like warm clothing, blankets, and mail became constrained. The Department of Correctional Services (DOCS) was characterized by laughably inadequate grievance procedures, insufficiently staffed facilities, anemic responses to ongoing labor-management disputes, rifts between uniformed and civilian employees, and failure to address racist and sexist barriers to fair treatment for employees and the incarcerated population.

Recent memory generated a foreboding sense of where all this would lead. In 1971, increasing frustration with inhumane treatment led directly to the Attica Correctional Facility rebellion. Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s decision to replace peaceful negotiations with the murderous retaking of the facility led to ghastly results: 128 men shot, 10 hostages dead, 29 prisoners killed. In the years that followed, the state failed to prosecute a single state official or employee, instead charging 63 prisoners with over 1,200 separate crimes.(3) The state implemented some reforms following Attica, but more notable was the state’s spearheading a national shift toward the use of lengthy prison terms with the 1973 passage of the Rockefeller Drug Laws, which set then-unheard-of sentences of fifteen years to life for selling or possessing narcotics.(4) By the time the state’s prisons began to buckle under the pressure of new entrants, Rockefeller decamped Albany to serve as Gerald Ford’s post-Watergate vice president. Malcolm Wilson, his lieutenant governor and successor, lost the 1974 race to Hugh Carey, a Democrat who would face the exploding prison population amid fiscal struggles that impeded the state’s ability to borrow funds necessary for new prison construction.(5) Under Carey, mid-1970s cost-cutting led to further erosion of the state’s prison reform tradition, which led to yet another uprising. In 1977, forty people incarcerated at Coxsackie Correctional Facility, a medium-security facility near Albany founded as a New Deal–Era vocational reformatory, took three hostages in protest of increasing violence by correctional officers and a reduction in the facility’s unusually expansive vocational training and programming. This incident ended quickly and peacefully but failed to have a meaningful impact on the Department of Correctional Services; nor did it impede the legislative push for continued use of long-term incarceration for a wide range of offenses. Instead, as historian Joseph Spillane notes, the incident served as a fitting coda to the reformatory era.(6)

In 1983 the uprising would take place at Sing Sing, one of the oldest and most infamous prisons in the world. After many months of using peaceful means to change inhumane practices and conditions—including the state’s own grievance procedures and nonviolent protest—failed to create change, inmates in Sing Sing’s B Block took control of the block and held nineteen employees hostage for three days. Thirty years later, Lawrence Kurlander, who served as the state’s director of criminal justice during the revolt, noted, “nobody remembers that prison riot, because we handled it very differently from the Attica prison riot.”(7) Attica cast a long shadow throughout the Sing Sing ordeal. People incarcerated in B Block chanted “Attica!” just hours prior to overtaking the block, indicating that a takeover was imminent and perhaps also as an expression of solidarity with the previous decade’s prisoners’ rights movement. During the takeover, the inmates hung a banner in full view of the assembled media on which they wrote “We Don’t Want Another Attica,” expressing their memory of the violent retaking of that prison.(8)

To be sure, DOCS and inmate negotiators should be remembered for not repeating the mistakes of Attica. They reached a relatively peaceful resolution despite the improvised weapons of the inmates, heavily armed state forces, intense scrutiny of the New York news media, and grandstanding politicians. But there are other reasons why we should remember the Sing Sing revolt of 1983. The Sing Sing revolt broke the chokehold. It pushed elected officials, especially the governor and his director of criminal justice, to rapidly expand the state’s prison capacity. Seeing the revolt as primarily the product of overcrowding, they convened a blue-ribbon sentencing commission that barely questioned the sentencing practices that were the central cause of the overcrowding in New York’s prisons. Their actions guaranteed continuation of the upward trajectory of the prison population through the final decades of the twentieth century. Furthermore, the revolt served as the catalyst to shift the priorities of the Urban Development Corporation, created in 1968 to bring jobs and economic development to underdeveloped areas of New York City.(9) The doubling of the size of the state’s prison system would be achieved through funds meant to support the very communities that sent its sons, brothers, and fathers to Sing Sing.

The state’s response to the Sing Sing revolt demonstrates the aftereffects of what historian Elizabeth Hinton calls the transition “from the war on poverty to the war on crime.” Rather than solely the product of clichéd “tough on crime” conservatism that led to the initial surge in incarceration, the prison-building boom of the 1980s and 1990s was also the product of “criminal justice liberalism.” Under Cuomo’s leadership, New York’s liberal politicians and corrections officials built dozens of new prisons in order to address long-standing complaints by correctional officers and incarcerated people about dangerous and inhumane conditions. The state’s leaders did not typically argue in favor of more punishment, and they even proposed some alternatives to incarceration, but they did not heed calls to roll back the relatively recent sentencing practices that led to the overcrowding. Rather, they implemented new determinate sentencing practices they hoped would prevent racial bias from influencing sentencing disparities but which also contributed to the overall rise in the size of the prison population. In order to fund this expansion, they transformed programs initially created by antipoverty liberals of the late 1960s and 1970s into a funding tool to build these prisons. This combination of liberal means and goals disassembled antipoverty liberalism and refashioned it as criminal justice liberalism. This, as much as anti-government conservatism, had a chilling effect on the antipoverty and urban renewal programs as state resources went from housing and job creation for the residents of the impoverished neighborhoods to building new prisons in more rural parts of the state.

Thus, if Sing Sing’s inmates revolted to address longstanding unresolved grievances, they also unwittingly left behind state-level evidence for how the apparatus of postwar liberalism was instrumental to the development of mass incarceration. We are increasingly aware of the way that mass incarceration was made possible as much by the rise of postwar liberalism as by the tough on crime rhetoric typically associated with the New Right’s effort to discredit New Deal and War on Poverty programs. As Julilly Kohler-Hausmann noted, if 1980s criminal justice policies served to undermine welfare programs, they also “built upon the welfare state.”(10) Republicans and moderate Democrats may have been the loudest voices driving mass incarceration, but the structures and programs of pre– and post–World War II liberalism facilitated the transformation of antipoverty programs into prisons. On the federal level, conservatives and moderates dismantled welfare programs while expanding funding for crime control. Elizabeth Hinton found that though the War on Poverty and the War on Crime were both products of Johnson-era liberalism, by 1980 the former had been eclipsed by the latter. Even before Reagan’s 1981 inauguration, funding for “federal crime-control measures ballooned from $22 million in 1965 to approximately $7 billion.”(11) Rather than combat racism, support education, end poverty, provide nutritional security, or build housing, federal policy and dollars increasingly supported militant policing and long-term incarceration.

This represented a transformation of liberalism as much as a dismantling of the welfare state. In the 1980s and 1990s, moderate Democrats, including Senate Judiciary Committee chair Joe Biden and President Bill Clinton, championed three-strikes laws, mandatory minimums, and the use of federal dollars to fund local police forces. Clinton couched his support for the expansion of policing and prisons in the language of liberalism. According to Naomi Murakawa, Clinton saw his crime bill as a compassionate effort to free poor people from crime-ravaged communities.(12) These policies, he hoped, might also neutralize conservative talking points that successfully targeted Democrats like Mike Dukakis as “card-carrying liberals” who were soft on crime.(13) What has perhaps been less well understood in the critique of New Democrats like Clinton are the ways that leading liberals of the 1980s like Ted Kennedy and Mario Cuomo contributed to mass incarceration by promoting policies and practices they believed would make the criminal justice system more fair, more humane, and less racist. Liberal efforts like Kennedy’s Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 sought to address racially disproportionate sentencing but ultimately contributed to across-the-board lengthening of prison sentences and an escalation in the use of the death penalty. Furthermore, these efforts to level punishments across race and class backfired when, in 1986, as Murakawa notes, “Congress established the infamous 100-to-1 ratio, giving a five-year mandatory minimum for trafficking 500 grams of powder cocaine or five grams of crack cocaine.”(14) African Americans would soon account for 88.3 percent of all crack cocaine convictions, while 75 percent of all those who reported powder cocaine use were white.

Previous New York governors tried and failed to address the growing incarceration crisis. The economic crisis of the 1970s prevented construction of new facilities from regular tax revenues even as elected officials pushed for an increasing reliance on long prison sentences for a broad range of convictions that would not have resulted in significant prison time in prior generations. If the money had been available, construction and state procurement logistics made it nearly impossible to keep up with the rate the prison population was growing without bringing other state operations to a standstill. Early in the 1970s, New York operated 21 facilities holding just over 12,000 men and women. By the early 1980s, the state’s prison population stood at over 30,000. It would more than double again, to over 60,000 by the mid-1990s. According to DOCS estimates, the system received 400 new admissions per week in 1982. These 20,000 new admissions per year would be offset by only 12,000 annual releases. In response, the state converted some drug treatment and mental health facilities to prisons during the second half of the 1970s, but these steps could not keep pace with the accelerated rate of prison population growth. This solution also meant that the state offered fewer facilities for treatment and rehabilitation at a time of rising demand for these services. It is reasonable to conclude that the conversions of rehabilitative alternatives to prisons would, before too long, intensify the problem of overcrowding as people with mental illnesses or addictions wound up in the penal system.

Incarcerated people, correctional bureaucracies, and elected officials struggled to respond to the consequences of startling new laws that simultaneously made it easier to receive a prison sentence and harder to get out.(15) Nationally, there was a clear and persistent trend to incarcerate large numbers of people during the final decades of the twentieth century, from 200,000 in the 1960s to over two million in the early twenty-first century. The impact of large inflows of people, reduced rehabilitative services, and insufficient funding for new prison construction first emerged in New York City’s Department of Corrections.(16) In late 1974 a federal judge ordered the city’s Men’s House of Detention—the infamous “Tombs” prison in lower Manhattan—closed due to inhumane conditions. In response, the city slated three detention centers for closure, including the Tombs, causing more overcrowding at the city’s main prison complex at Rikers Island. In addition, the city’s underlying financial problems led to cuts in civilian and uniformed staff, as well as to drug rehabilitation and other social welfare programs, including those that sought to alleviate housing and nutritional insecurity.(17)

Keep up with us, join our newsletter.

Thanks to Michael McGandy and the New York History Journal. You can subscribe to the Journal here.

This research benefited from insight gained from Joe Britto, Lisa Gail Collins, Andy Evans, Judith Weisenfeld, participants in Princeton University’s American Studies Workshop Series, and feedback from the anonymous reviewers for New York History.

- New York State Committee on Sentencing Guidelines, Determinate Sentencing: Report and Recommendations(Albany, NY, 1985), 15.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010).

- Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (New York: Pantheon, 2016). Governor Hugh Carey vacated the few successful prosecutions of Attica’s prisoners.

- Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, “‘The Attila the Hun Law’: New York’s Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Making of a Punitive State,” Journal of Social History 44 (September 2010): 71–95.

- Kim Phillips-Fein, Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017), 194–95.

- Joseph Spillane, Coxsackie: The Life and Death of Prison Reform (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014). Coxsackie is now classified as maximum security. There was another uprising at Coxsackie’s Special Housing Unit (SHU, or solitary confinement) in 1988. See Bert Unseem, Camille Graham Camp, and George M. Camp, Resolution of Prison Riots: Strategies and Policies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 107–20.

- Lawrence Kurlander, quoted in Owen Lubozynski, “Lawrence Kurlander ’64: Looks Back on Three Careers (and Counting),” Cornell Law School Spotlights, http://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/spotlights/Lawrence- Kurlander-64-Looks-Back-on-Three-Careers-and-Counting.cfm, accessed August 16, 2017.

- Sydney H. Schanberg, “Attica on Their Minds,” New York Times, January 11, 1982, A19.

- Mario Cuomo, quoted in Susan Chira, “Budget Proposes Space for Additional 2,300 Prisoners,” New York Times, February 1, 1983, B5.

- Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, “Guns and Butter: The Welfare State, the Carceral State, and the Politics of Exclusion in the Postwar United States,” Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (2015): 89.

- Elizabeth Hinton, “‘A War within Our Own Boundaries’: Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and the Rise of the Carceral State,” Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (2015): 111. See also Hinton’s From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

- Naomi Murakawa, The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- Hinton, “A War within Our Own Boundaries,” 113

- Murakawa, The First Civil Right, 122.

- Todd R. Clear and Natasha A. Frost, The Punishment Imperative: The Rise and Failure of Mass Incarceration in America (New York: NYU Press, 2014). Clear and Frost identify a “relentless punitive spirit” and “grand social experiment” that gave shape to the post-1960s criminal justice system. See also Jordan T. Camp, Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016). Camp contends that mass incarceration emerged specifically in response to the class anxieties resulting from the intense antiracist activism of the 1960s and 1970s; see also Alex Lichtenstein, “Flocatex and the Fiscal Limits of Mass Incarceration: Toward a New Political Economy of the Postwar Carceral State,” Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (2015): 113–25.

- By the end of 1975, historian Kim Phillips-Fein notes, the city’s main jail for men at Riker’s Island reduced the uniformed correctional staff from 500 to 340. The New York City Department of Correction saw an overall reduction of 350 officers and 150 civilian employees—500 people from a total workforce of 4,400 (Phillips-Fein, Fear City, 202).

- “The Rikers Revolt Was for Rights Already Won,” New York Times, November 30, 1975, 6.