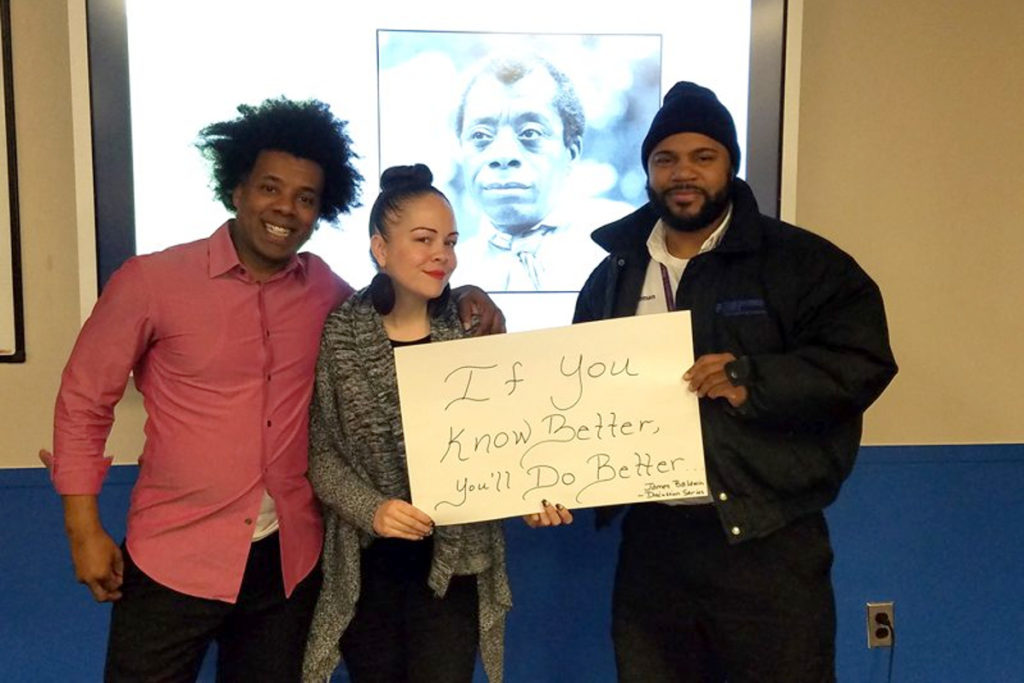

“James Baldwin’s America” continues to be one of the most popular and challenging discussion programs Humanities New York offer. Here, we check in with two of the discussion facilitators for the program as they recount how the program has changed their lives and the communities they have worked in.

HNY: You talk in your essay about your initial encounter with Baldwin’s writing, and I’m wondering if there are any other experiences or history that you have reading Baldwin’s work, or moments that stand out to you that might have prompted your desire to share Baldwin with other people, or re-engage with Baldwin yourself.

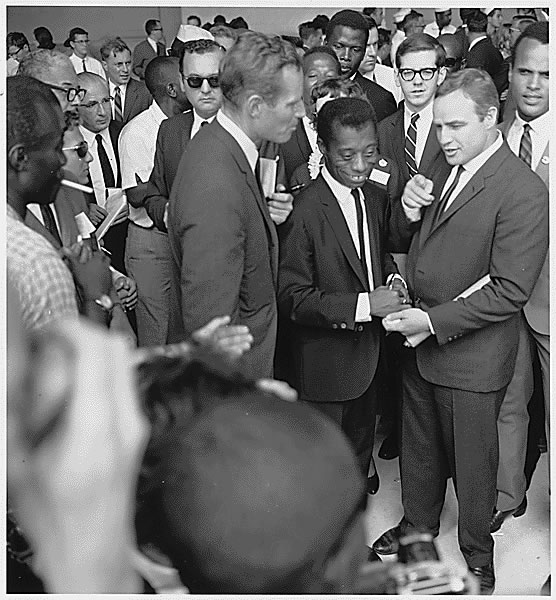

Lindsey: I was right on my way to grad school and I read a bunch of his work and it really hit me in a powerful way, for one because no one had yet in my intellectual advancement had really talked about Baldwin, and I was amazed because I hadn’t really encountered him before, because he was clearly to me a very important voice, a very powerful voice. So when I got to grad school, when I was working on my dissertation which was on Paul Robeson, I encountered some other historic moments with Baldwin, as well as in my first book, which was on Paul Robeson’s three portrayals of Othello. And there was this celebration of Robeson in the 1960s at a time when a lot of people had kind of forgotten about him and he was considered kind of a earlier generation, and a lot of the radicals of the 60s didn’t yet know who Robeson was, and Baldwin speaks at this event. And so when I came across that speech, it really moved me yet again, and Baldwin spoke to this idea that Robeson was a voice that we still need to listen to. And he was speaking to a generation of young Civil Rights activists. And I quoted from that speech to conclude my book, because I thought no one could really say it better than Baldwin, right? That was another pivotal moment for me. For me, with Baldwin, it’s like you’ll encounter something, he sums up everything that you’ve been on the brink of saying, but he just articulates it so beautifully, and you go “yeah, yeah, that’s what I’ve been working toward and trying to figure out!”

Grant: My experience working with Baldwin has been through working with Doc Lindsey here. Because when I was in high school, I did take African-American history–they just started it for us my senior year–neither Baldwin, nor Paul Robeson, was ever mentioned. Then I went straight to the military at seventeen and I was stationed at Charleston on a ship named after a Confederate general. So I got to see how deep racism can run in our country; even though I had experienced it being a young black man I was amazed at the depth, at how far it really went, when I was in the military.

So Doc and I started talking about Baldwin, and I read a little bit about Baldwin and I saw some videos of him on YouTube, and he was articulating what I had lived. I couldn’t say it as eloquently as he had; I don’t think anyone can really. There were a lot of parallels in Baldwin’s life to my life, like being the oldest and growing up in a religious home, kind of not fitting in, and he expressed that. And I like that he talks about, and of course I’m paraphrasing, if you really want to see where America is, just check how blacks are being treated, and that really stuck with me.

When I got hooked up with these charter schools and we started thinking about offering this to the kids it struck me in a powerful way because I wasn’t exposed to it, it was like a crime. And Doc and I agree on this a lot, about people’s interpretation of Baldwin, most times people don’t talk about how he preaches about love, and that’s the thing a lot of people seem to miss, that he ended everything with “the only way we’re going to change any of these things is with love.” And he’s known for being so angry, which he was, but he never, in my experience, he never used his anger to put anyone down or to say his point is right and there’s no other point. He always ended with love.

And we believe that ourselves. It’s hard, and I can tell you as a black man who was in the military, it’s very hard to come from a place of love when you’re so bitter and you’ve been wronged and when you bring that to the table, a lot of people can’t get past their own feelings. Baldwin to me articulates what I’ve always been practicing, which is that I know I’ve been through stuff, but it doesn’t matter if that’s all I’m ever going to talk about and preach about and argue about. And that’s my experience, and what makes me a Baldwin fan, and a Baldwin torchbearer, so to speak.

HNY: So that ability to articulate those experiences, or as Lindsey said, that ability that Baldwin has to summarize so nicely all those things that you’ve been trying to get at, do you think that’s why he’s been resonating so much recently, or why people seem to be rediscovering him lately?

Grant: We believe, not only his way with words, but also that he was ahead of his time, we’re still going through it. His eloquence is something that added on to it–he could have just been fiery, you know what I mean? And I’m not used to the words that he used, but he doesn’t lose me. But he does talk in eloquent language that everyone can pull something from. Because it’s not like I’m highly educated. I looked up the definition of the words. The main thing about Baldwin for me is that if try to read it without any preconceived notions, it’s going to affect you one way or another. What you do with those feelings is a whole other thing, but he’s not talking down to anyone and he’s not talking up to people, he’s talking straight to the people.

Lindsey: I feel like a lot of people are trying to understand this moment and how we got here, and of course the historian in me wants to say, that’s a long story, but I think when Baldwin says things like “Americans are trapped in a history they don’t understand” that’s a phenomenon that’s still occurring, that’s his challenge to Americans to take the personal responsibility of understanding and reconciling with the true history of this country. That hasn’t happened, and since that hasn’t happened, as we look for answers, there’s still really no voice that says that more clearly than Baldwin. This came up in one of our sessions, one of our conversations, I remember a man asked us, who’s the Baldwin of today? And a lot of people say Ta-Nehisi Coates, and his writing is good, but I would say still next to Baldwin, Baldwin’s voice is still the more resonant. I was teaching a Civil Rights class this summer, and we, coincidentally, read Ta-Nehisi Coates right next to one of Baldwin’s essays, and the students felt that Baldwin’s was actually the more current, the more contemporary-feeling. So I think that what he observed about American culture sadly hasn’t changed and that makes him a really important voice for this moment.

HNY: When you were running the conversations, who did you find in the room with you, and how did they react to Baldwin’s writing?

Grant: We had a little bit of everybody. That was the amazing thing about it. We had people who had never read Baldwin, and people who had, we had one black lady who read Baldwin in the 70s when she was in school and picked it back up and started sharing it with her daughter. So we were fortunate to have a little bit of everybody.

Lindsey: We did five sessions at a middle school in Harlem, and then other schools in that network heard about that, and then we were invited to go to a high school and do five sessions, which went really well. So at the school sessions we had students, teachers, staff, and even parents as well.

Those were all going so well that we adapted the HNY program to do a single evening with Baldwin, and we’ve been doing that with the New Jersey Humanities Council Public Scholars. This year we’ve been going all over New Jersey to do evenings with Baldwin–Trenton, Perth Amboy, all up and down New Jersey, we did eight events. Those were really diverse events, we had people who came out on a rainy Saturday, it was amazing!

Grant: Older white people, young black people, people with their kids, male, female…

Lindsey: …people who had been to Baldwin’s funeral, we had that older couple…

Grant: …yup, people who had met Baldwin.

Lindsey: People who had never read or never heard of Baldwin!

Grant: But they saw the ad or the flyer for it and came in. With the library sessions, people asked, “what can I do?” because they were so motivated and what we threw back to them was, you do what you think you can do, use the talent you have. Because that’s basically all that we’re doing, we’re creating these platforms as well, but Doc is the African-American history scholar, and I’m the African-American history, and I’m a stand-up comic and actor as well, so we pool those things together. At the high school we had parents who came in every week after work. And they would stay and talk afterwards, and they would kind of co-sign what we were saying. And we would try and say it gently, we’re not preachers, about the importance of Baldwin and how significant it is that they can talk about Baldwin now and how real it is, and their experiences from back when they were their kid’s age, and that was amazing.

Lindsey: With the young students, we would pull out portions of essays, and have them read that at the beginning of sessions and talk that over, so it wasn’t really a thing where they had homework, but everyone could join the conversation. A lot of the things that really resonated with the kids were Baldwin’s essay where he talks about being arrested on the streets of New York, or when he’s just showing his friend around the city–it’s those kind of moments when he’s describing something in a visceral way that the students were really connecting with him. Then we would make present day connections, the kids would connect it with Colin Kaepernick or the Confederate monuments or Trayvon Martin, Trayvon is a big generational touchstone for these kids, they talked about him a lot. We’d bring up somebody like Rodney King and they’d be like who?

Grant: Yeah they didn’t know who he was, but I wouldn’t let them get away with that, I’d tell them go Google it because you Google everything else! And I don’t want to preach like “back in my day” but we would have to go the library and they have it right here! But you know I was going to bring that up, that’s interesting Doc. If they don’t know Rodney King and that situation, well how hard would it be to sell Baldwin, because that’s going to back to when my mother was young. But Doc is very good at coming up with how we’re going to roll stuff out to people, and once we get people to read his words or hear his words, whether I’m reading them or not, then that’s it, because his words are that good. It’s just bridging the gap, getting people to actually be there, his words are like seeds that just keep growing.

Lindsey: I think one of the big themes that stands out to me from all the Baldwin work that we’ve done in the past two years is that there’s a real desire to just simply be heard, and I feel like in the end what we were creating was this moment where we would talk about something Baldwin said and see how it touched people, and give people a moment to sit with it and see how they process it, and then give them the space to talk about what it means to them. I think people have a deeper need right now to connect and communicate with each other on a human level and be recognized and know that their suffering is also recognized. And I think Baldwin’s words offer a beautiful vehicle to help facilitate that happening.

I remember a lot of sessions where we would walk away and people would be thanking us for coming and I felt like we didn’t really do that much. We told them about us and offered some Baldwin and then they would just talk, we would sometimes go an hour over the time we were scheduled.

Grant: Yeah there’s some Baldwin conversations we could still be at today. Because we’re making history now. So we’re responsible for how people are going to look back at this time. And so you have to get past yourself to see that I think. It’s tougher for blacks in certain situations, and then it’s tougher for women. I don’t know what it’s like to be a woman, but I’ve seen how women get treated, no matter what color, and that’s the special thing that I think Baldwin tries to articulate.

HNY: What have been some difficult moments in your conversations?

Grant: We’ve had within the discussions people who’ve tried to hijack the discussion, because you know you open it up to whoever’s there, and you never know who it is, but we’ve learned to be extremely compassionate, and it would defeat the purpose of having the discussion if you want to shout down some voices. But we’ve had points where it would get almost heated, especially around religion, and Baldwin used to be within the religion, I think his greatest power was that he didn’t attach himself to any religion, he just attached himself to what he thought was the truth, no matter where the truth took you. I guess what I’m trying to say in a long way is we’ve been very lucky to experience people experiencing Baldwin, but it’s like a boomerang because it came back at us as well.

Lindsey: In Perth Amboy we probably had close to fifty people there and the discussion went on and on, and when they dropped us off at the train station we hugged and we felt so connected to these people because of the authenticity and the sincerity that people brought to the conversation. It’s really something special, I feel that when people walk away and when we walk away we feel like there’s been a real human moment, and we always end it on a note of love, with a quote from Baldwin about love, and about how we need each other and about how we have to support each other. So no matter what happened in the course of the conversation we would come back to that point and remember, hey we all have our experiences but we’re all also in this together and we can’t move forward without each other.

Grant: Right, and we have a lot of people who only see the blackness of Baldwin or the anger of Baldwin pointing the finger at white America and nothing else. We’ve been lucky enough to present Baldwin as we see him, but we don’t go into it as though we’re Baldwin scholars, we go in to share his writing and open up the dialogue. A lot of people are well-versed in Baldwin, but what are you really doing? Because if you’re not doing something, even if it’s just sharing Baldwin with someone, you’re not doing Baldwin’s work any justice. So we’ve been lucky to put it out there, and we’ve gotten so much back from our audience members.

Lindsey: These events have been for me some of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done in my whole career, bar none, these conversations have been truly special.

Grant: Yeah. I think Baldwin’s a great example of how to use your anger, your hurt, your sadness, all those deep emotions that can take you down a rabbit hole, and make lemonade, that kind of stuff. Fact is fact, he was a very angry, hurt, sad man, but we’re sitting here enjoying the fruits of what he did in a positive way.

HNY: So, what’s going on now? Are you continuing the conversations you’ve been running? Are you planning on adding to them?

Lindsey: We’d love to do more! This summer was the last of eight conversations all around New Jersey from February to June, and that was a lot. We’re still part of the New Jersey Humanities Council Public Scholars catalog, so that new session will start up soon, we’ve got some new dates for February booked for black history month, but we’re thinking more about will happen in the new year.

Grant: What we try to do, the whole black history month thing is like an anchor. But Baldwin and Robeson, those may be black voices, but they’re also everyday voices, so what we can do these discussions any day, any month, because its everyday that we’re Americans, it’s everyday that we’re making history.

Interview by Adam Capitanio, Senior Program Officer

Keep up with us, join our newsletter.

- Swindall’s There is No Texting at James Baldwin’s Table

- Host your own Reading & Discussion program

Grant Cooper is an actor and stand-up comic who has been living and working in the New York City area since the late 1980’s. He specializes in scenario-based training which uses professional actors to train employees to navigate specialized communication situations. Through Winfield Artists, LLC, he works with charter schools and other organizations to develop scenario training programs. He also portrays African American actor Paul Robeson in a program designed to inspire young people to achieve their highest potential.

Lindsey R. Swindall holds a doctorate in African American History and teaches U.S. History and the Freshman Colloquium at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ. She has written several books including The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955 which will be out in paperback from the University Press of Florida in July 2019. Working with actor Grant Cooper, she has developed a dramatization of her biography of African American actor Paul Robeson for middle and high school students.