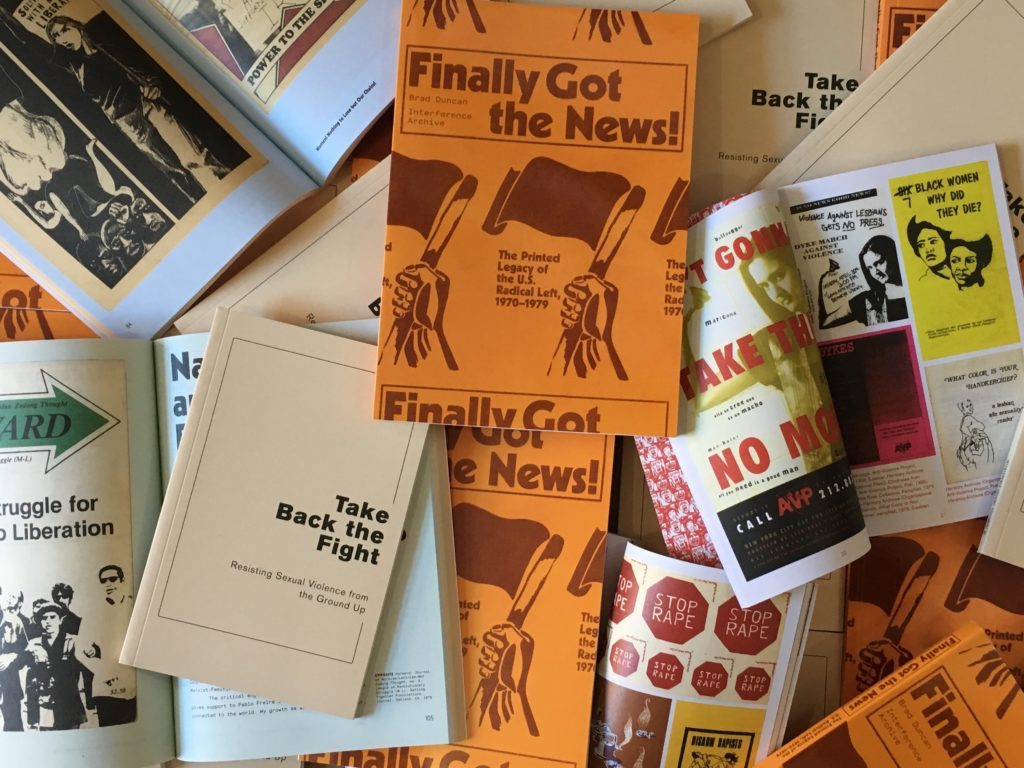

Powerful graphic design and social mission intersect in “Finally Got The News,” an exhibition at Brooklyn’s Interference Archive funded through a Humanities New York Action Grant. The mission of Interference Archive is to explore the relationship between cultural production and social movements. This work manifests in an open stacks archival collection, publications, a study center, and public programs including exhibitions, workshops, talks, and screenings; all of which encourage critical and creative engagement with the rich history of social movements. Last month we sat down with project director Jen Hoyer to discuss the Archive and this exhibition.

HNY: Tell us a little bit about how “Finally Got The News” came about and what it means to your organization.

JH: This project happened at Interference Archive, which is an archive that collects ephemera from around the world. Our mission is to explore the relationship between the production of that material and social movements. We have an archival collection, and we also have an open stacks space for people to use the collection. We also host public programs like workshops, talks, and film screenings. Since we have opened our space we’ve had a public exhibition series. In some sense the exhibition series comes out of the realization that people don’t necessarily, intuitively, think it’s fun to go to an archive and open boxes and pull things out and talk about them, but if you put it on the wall, that starts a lot of conversations. It’s a really great entry point for people to go look for more things in the archive. So we do these public exhibitions to create community engagement, as a tool to partner with the communities that the work came out of. Then we can put the material on the wall and we can tell stories about it and maybe tell stories that aren’t being told in other mainstream venues, either from a perceived lack of interest or a lack of support from traditional institutional decision-making bodies. We are really trying to activate what we call “history from below,” or grassroots history. Engaging people in alternative narratives about themselves and their communities.

HNY: Was there a specific impetus for “Finally Got the News”?

JH: For this exhibition, Brad Duncan, who is a private collector based in Philadelphia, reached out to us. He had heard of our work and he had amassed a really big collection of material from the 1970’s radical left. He wanted to put together an exhibition with that material so he reached out to us to collaborate. This exhibition included materials from his collection supplemented by the Interference Archive collection. It was a nice opportunity to collaborate with another archival collection.

HNY: How did that exhibit concept catch your interest, among all the other ideas people throw at you?

JH: It was really interesting to Brad that the 1960’s were seen as the decade of radicalism and there tends to be an assumption that things had started to decline in the 1970’s. And while to a certain extent that was true, Brad really wanted to showcase the 70’s. For us, having a collection of mostly print material from social movements, we recognized that the 70’s were a really key point for community organizing groups because it was a point in time where there were much simpler means for printing and sharing ideas. So, while groups were definitely able to print their own materials before that time, it became much cheaper and easier for a political organization to print out their own newsletter. Liberation News service was one of the more formal cases of distribution of stories and images to be used in all of these newspapers, and then community newspapers would take things out of other newspapers, cut them out and put them in theirs, all these different organizing groups. So suddenly the level of communication increased. It was important for us to draw the connection with this exhibit between the new technology emerged for printing newspapers and the explosion of intersectionality that laid the foundations for a lot of the intersectionality that happens today. Because a women’s organizing group saw connections between their work and police brutality, prisons, and anti-war organizing, they could just take that info from whatever groups were printing that and insert it in their own newsletter. They could share those ideas and causes more broadly. It’s really exciting to look at how communication exploded in the 70’s and how people who were working on different issues began to support each other’s work in new ways.

HNY: How did you approach displaying intersectionality in the exhibition?

JH: What really stood out on the walls in the exhibition, and this is an conversation we have with any public programming we do, was how many items could you argue to put in different sections. You know something that is on the wall in the labor organizing section could fit just as well in black nationalism, and some in the women’s liberation section would fit just as well in anti-colonialism. That was all really obvious looking on the walls, and it was great to see it all in one space and draw those connections out.

HNY: You also held also panel discussions, a podcast, a party, and a reading group, among other things. How did those work in connection with the exhibition?

JH: We do these exhibitions to increase access to the materials, but when you put things on the wall behind mylar you actually can’t read it. This was mostly material that was created to be read, so I said I feel will okay putting it on the wall behind mylar if we scan it and have a reading group where we read the material. I was really adamant about this! Our reading group met 12 times over the course of the exhibition, just about weekly, and we read the material in advance. That was a really fantastic way to get more in touch with the ideas in the exhibition. We also did an event where we invited people to come talk about all the different graphics and symbols they saw on the wall in the exhibition. We had a discussion about which symbols we saw a lot of, what issues or movements we didn’t see great symbols for, and what symbols we might create. Then we used foam that we carved to do lino printing, we made stickers and zines by sharing the different symbols that we copied off the wall or made. That was a really neat way to interact with it. We had several film screenings, we watched films that had been made at the time and then had discussions with the filmmakers or the activists shown in the films. We invited one group, who were working on their own archive of materials to do with the 1970’s Puerto Rican independence movement, to come and give a talk about that work. We tried to provide a lot of different ways to interact with the exhibition and also to interact with ideas that were maybe important, but not represented on the walls.

HNY: Is there anything you would have changed about the exhibition or other programs if you had done the reading group first?

JH: Great question. One of the ideas that we explored through the reading group and film was the austerity measures in NYC in the 1970’s and the activism against those austerity measures. Those were really meaningful conversations to have in terms of NYC, but because the scope of our exhibition was about the United States, it might not have made sense to have a NYC austerity section. However, having the reading group was really important to exploring that idea even without having it on the walls. Every item was printed in the United States, but a lot of it was from American groups that were promoting anti-colonialism or anti-war activism, so a lot of the material was about other countries. We were really strict about where it was printed because you have to draw a line somewhere. Even as we were hanging the exhibition there were one or two posters where we said “OMG this was printed in Australia, how did we not notice, we have to cut this.”

HNY: You’ve been pushing the limits of what an archive can be to the public, give an example of your more unconventional work.

JH: Absolutely, one of the types of events we do every few months is a propaganda party. We work with organizations that are focused on a specific issue in the city and we’ll print some posters and stickers related to the issue. We reach out to designers in our community to get designs with whatever funding we can find. We’ll also do live screen printing so people can make their own posters, T-shirts, jackets, and buttons. So we were doing that around May Day, we wanted to create a lot of material that people could take out to May Day actions. We try to draw connections between the materials we have in our collection and what’s going on in the community right now and show how an archive can support current work in a community. We didn’t have any good designs for May Day, so we took a design from out of the exhibit and we were screen printing that at the event. People were able to walk away with a reproduction that they had just created of something on the wall in the exhibition. That was a really neat way to connect the exhibit to what’s going on in the streets right now.

HNY: And what about the humanities, how do they inform your work, do they matter to what you do?

JH: The humanities matter because they’re a set of disciplines that invite us to ask questions about ourselves as a society and culture being in the world, and to explore what it means to be human both now and across history. Having space to ask those questions and share different viewpoints is critical for us all to appreciate and celebrate the various ways we all understand ourselves, our communities, and the narrative that brings us through history to the present.

HNY: What’s next?

JH: We moved, and we’ve now reopened at 314 7th Street in Brooklyn (just off 5th ave in Park Slope). Our current exhibition is Take Back the Fight: Resisting Sexual Violence from the Ground Up and it’s also been an exhibition that has created space for conversations that are really timely.

Interview of Jen Hoyer by Nicholas MacDonald, Humanities New York

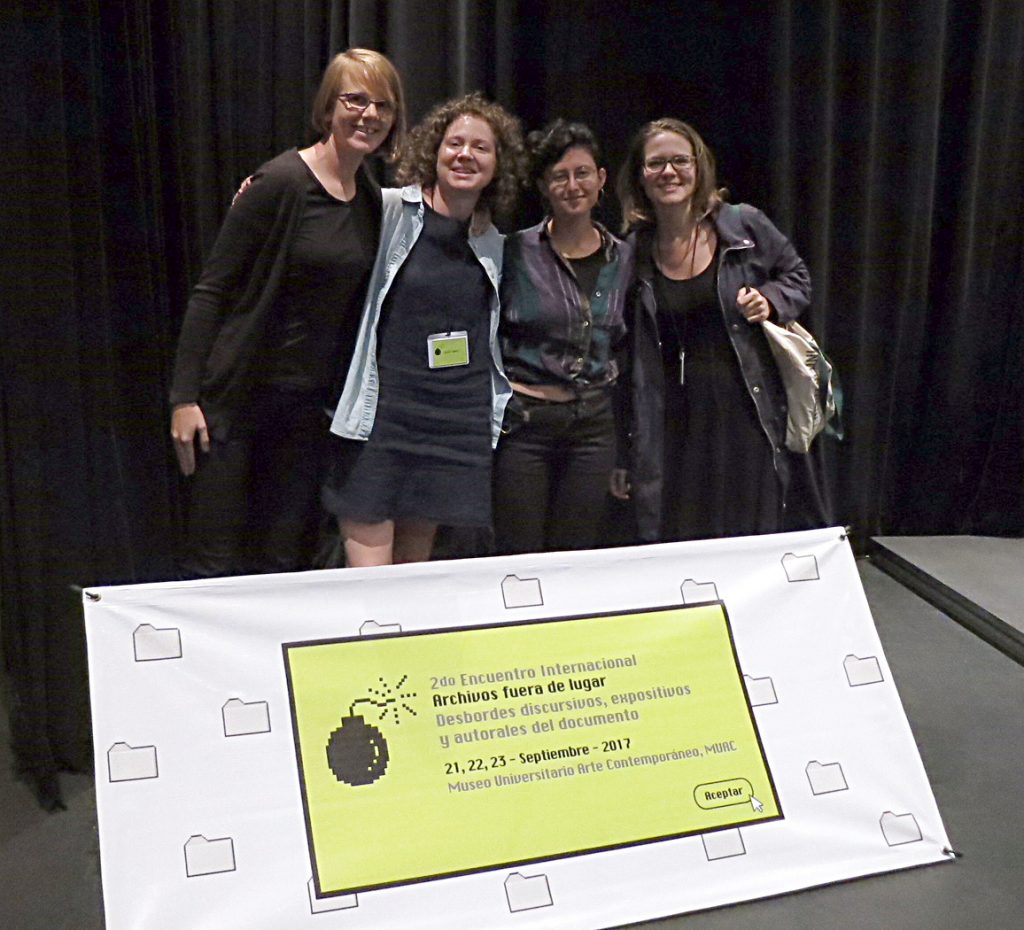

From left to right: Jen Hoyer, Louise Barry, Lena Greenberg, and Amy Roberts from Interference Archive

Jen Hoyer volunteers her time to organize programming at Interference Archive in Gowanus. She is an Educator with the Brooklyn Connections program at Brooklyn Public Library.